PhD mental health: From awareness to action

The facts surrounding PhD mental health are shocking. With 1 in 2 postgraduate students experiencing mental health issues during their PhD,1 yet only 35% of students with anxiety or depression finding useful help at their institution,2 it is clear that studying for a doctorate can come at a cost. While a dialogue has begun, with a range of scientific magazines getting involved in the conversation34, little has been done to highlight what can be done to improve the PhD experience. So how do we fix this epidemic? Given that one person’s mental health struggle can be very different to the next and there is no one-size-fits-all solution, it’s easy to place the responsibility of ‘fixing’ the mental health problem with the student, rather than addressing the institutional, cultural and environmental factors that contribute to feelings of despair, depression and anxiety. Of course, it goes without saying that anything a student can do to help improve their own mental health is incredibly important – from increasing exercise, seeking medical help to taking time away from research. However, self-care is often the only option available for students, given that, like many large institutions, universities are often slow to embrace and enact change, or worse, have yet to acknowledge that mental health at the postgraduate level is even an issue. So, what can universities do to improve the PhD experience?

Train the trainer

Let’s start by recognising that being a great academic does not come hand in hand with being a good manager or leader. In a ‘publish or perish’ culture, where emphasis is placed purely on research outcomes, perhaps it’s time to consider that enabling others to continue with research by having a positive experience, rather than forcing them out of the career due to a toxic culture, is time well spent. Routine mandatory training in team management, mentorship and people skills for academics is essential for a healthy workforce. It’s also worth noting that the system can be self-perpetuating. If academics do not have the emotional depth to support students, the students most affected are likely to leave academia, never making tenure. It is these students that leave academia behind that are in the best position to inform change, yet their experiences are rarely collated and capitalised on – thus the cycle continues.

Be accountable

Undergraduate students are actively encouraged to participate in the National Student Survey (NSS) which assesses student satisfaction and provides opportunities for students to provide improvements for their institution. This year, the NSS had over 100 UK universities participate in the survey to evaluate student satisfaction in 20195. In contrast, only 63 UK institutions participated in the latest postgraduate research equivalent, the Postgraduate Research Experience Survey (PRES)6. It ‘s only by identifying where the challenges lie that improvements can be made. Therefore, universities should be actively advertising and pursuing honest feedback from their postgraduate researchers. Exit interviews should also be considered for PhD students. This provides the opportunity for students to speak up about issues such as harassment and poor treatment by supervisors that they may not have had the confidence to do when they are part way through their PhD studies. In cases of bullying and harassment, it is essential that universities hold themselves accountable and take all allegations seriously. Policies must be in place to ensure discretion and fair treatment of those affected, as well as ensuring swift action is taken against any academic that is found guilty of misconduct.

Stop talking about non-academic jobs as ‘alternative’ careers

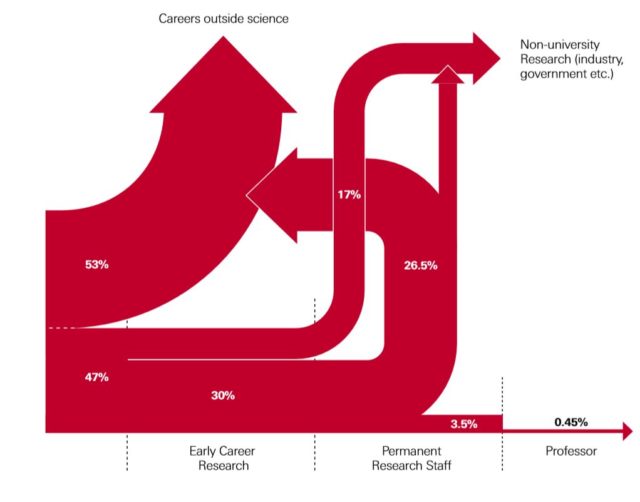

A report by the Royal Society states that approximately 0.45% of PhD students will become a professor, with as little as 3.5% becoming permanent research staff at a university7.

Therefore, the majority of PhD students actually find scientific careers outside science altogether, or go on to work in industry, publishing or science communication for example. Yet, all too often, anything other than following the academic track is touted as a failure, with phrases such as “selling out to industry” often used. Instead, emphasis should be placed on developing skill sets that are applicable to a wide range of jobs, both in and out of the sciences. It is worth noting that in many cases, transferable skills programs do exist at universities for research students. However, these programs existing are not enough. Often students feel pressured into not taking time away from their research, or in some cases, the supervisor is altogether dismissive of the benefits of personal development. Dedicated time for development during work hours should be provided, to be used at the discretion of the PhD student.

Provide tailored mental health support

Often PhD mental health provision is rolled into one with undergraduate wellbeing and support services, yet the stressors that postgraduate students experience can be very different. For example, difficult supervisor-student relationships, imposter syndrome and ‘publish or perish’ pressure. “How to study better” workshops are likely not going to cut it for PhD students, who have proven they are more than capable of studying by obtaining their undergraduate degrees. Universities also tend to put on more wellbeing events around undergraduate exam times, even though PhD students would benefit from them all year round.

Initiatives such as the ‘Mental Health First Aider (MHFA) program have been shown to be effective at several UK universities, including the University of Glasgow, which provides opportunities for researchers to be trained to help others in their department. These people often act as a first port of call for people experiencing a mental health crisis. In this instance, if the MHFA has completed a PhD and knows the stresses first hand, they can ultimately provide a deeper insight and understanding to the issues PhD students are facing than someone who has not8.

Recognise financial burdens.

All too often, PhD students must pay for conferences and travel out-of-pocket, despite the small income (if any) that they are paid. If we consider international travel, this cost can add up to thousands of pounds. Coupled with slow reimbursement, this can genuinely impact the life of a PhD student, with worries about how to make ends meet. Responsibility lies with the institution to make sure students are not discriminated against due to their socioeconomic background, with some students choosing not to take development opportunities such as attending conferences as they cannot afford to wait for reimbursement. Better procedures need to be put in place, ideally removing the PhD student from the financial equation in the first place. Furthermore, opportunities to earn additional money, from laboratory demonstrating to tutorial work should be encouraged, with time designated to do this to minimise feelings of guilt that can arise from being away from research. These opportunities can provide financial lifelines for students as well as the chance to learn new skills.

Encourage an inclusive environment

With feelings of isolation often part of the PhD process, departments must do everything possible to promote a sense of community, by hosting social events and opportunities to share experiences. Focus should also be placed on celebrating collaborative work in an altogether competitive environment, to help move away from the dog-eat-dog mentality that can be incredibly damaging to mental health.

Diversity of academic staff is also incredibly important9. Without relatable role models, PhD students from underrepresented groups in academia including women, those from a poorer socioeconomic background, as well as those from the BAME community, are more likely to experience impostor syndrome – the belief that you are less capable than those around you10. With the choking self-doubt and increased stress associated with impostor syndrome, it is not altogether shocking that these peoples’ mental health may suffer, ultimately becoming disenamoured with the whole academic process.

Promote and enable work-life balance.

With the World Health Organisation labelling ‘burnout’ as an official diagnosis earlier this year, academia could well be the poster child for the phenomenon, with an inherent culture of acceptance in academia that in order to be successful, you must be working 24/7. In reality, inefficiency is common, with academics and students working long hours, but not being productive with their time. Universities have a responsibility to ensure that PhD students are not being taken advantage of by their supervisors, feeling forced to work seven days a week because ‘that is what everyone does’. Furthermore, working outside of typical work hours can add to feelings of isolation11. Mandatory out-of-hours sign-in sheets and querying regular out-of-hours working should be considered. Universities should be championing flexible working, as well as increasing the visibility of those that do, so that others feel empowered to do so. By enabling PhD students to also work flexibly, stresses and strains that can impact mental health, like balancing caring responsibilities can be reduced.

While this list is certainly not exhaustive, and the journey to improve postgraduate mental health is long, we have to start somewhere – by challenging our universities to actively address the rising mental health problem. If institutions need a financial incentive it’s worth noting that a happier workforce is likely to be a more productive workforce. Mental health issues do not stop at PhD level. By helping our PhD students, that go on to become postdoctoral researchers and ultimately (perhaps) professors one day that teach undergraduates, the whole system will benefit.

This article was specialist edited by Katrina Wesencraft and copy-edited by Kirstin Leslie.

References

- www.iflscience.com/brain/half-phd-students-suffer-psychologica-distress/

- https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v550/n7677/full/nj7677-549a.html

- www.sciencemag.org/careers/2017/04/phd-students-face-significant-mental-health-challenges

- www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01492-0

- https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/student-information-and-data/national-student-survey-nss/

- https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/institutions/surveys/postgraduate-research-experience-survey

- Read the full report here: https://royalsociety.org/~/media/royal_society_content/policy/publications/2010/4294970126.pdf

- Learn more about the MHFA program here: https://mhfaengland.org/

- Lack of diversity and role models contribute to the lack of retention of women in the chemical sciences, as outlined in the latest ‘Breaking the Barriers’ report by the Royal Society of Chemistry. https://www.rsc.org/campaigning-outreach/campaigning/incldiv/inclusion–diversity-resources/womens-progression/

- Read an interesting POV article about impostor syndrome here. https://thetab.com/uk/london/2019/07/29/imposter-syndrome-is-a-real-problem-so-why-arent-unis-taking-it-more-seriously-34658

- https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2014/may/08/work-pressure-fuels-academic-mental-illness-guardian-study-health