Antibiotic resistance: how do we get the threat under control?

At the dawn of the new decade, one of the primary threats to human health is antibiotic resistance. A future without working antibiotics could potentially become a reality. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), it’s currently the direct cause of 33,000 deaths each year. Risk factors such as the inappropriate consumption of antibiotics continue to feed the emergence and spread of resistance. Countries that have implemented national action plans have shown better antibiotic stewardship (more evidence-based prescribing) and overall lower human and animal use, in an attempt to curb resistance.

What is Antibiotic Resistance?

Antibiotics are medicinal products capable of killing bacteria or inhibiting their growth. They are divided into classes based on their mode of action and chemical structure. However, some bacteria are resistant and are able to withstand the effects of antibiotics. The bacteria continue to grow and multiply. As a consequence, they become untreatable, leading to longer illness in patients, and potentially even death. Longer illness translates to longer treatments and a need for alternative antibiotics. These drugs are often more expensive and might cause undesirable side effects. Problematically, resistance can also arise to the new antibiotics prescribed.

We commonly think of people being resistant to antibiotics when in reality they are being infected by resistant bacteria. This means people are not responsive to what would normally be effective treatments. Counterintuitively, most resistant strains actually belong to the normal bacterial flora of healthy people, animals, and within the environment. For instance, Escherichia coli is one of the most common gut bacteria and Staphylococcus aureus colonises the skin and mucosa of 20-30% of individuals – however, when we hear ‘E.coli’ or ‘staph infection’, we think of them causing serious illnesses and disease. They are responsible for ‘opportunistic infections’ that occur mostly in people with a weak immune system.

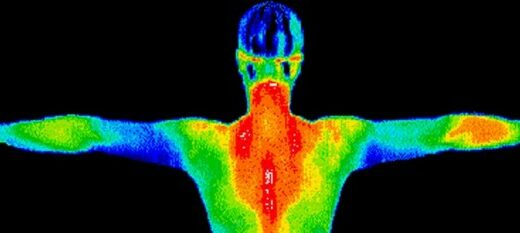

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria cause an array of infections depending on their location in the body and on the patient’s underlying immunity. This can range from skin infections and pneumonia, to diarrhoea and urinary tract infections (and many more).

How did we get here?

Antibiotics have saved and improved the lives of many around the globe for seven decades, being one of the most important therapeutic advances for human health. Their golden age has faded away with the rise of antibiotic resistance.

The ECDC mapped how antibiotic resistance spreads between key places1. One issue that contributes to resistance is when antibiotics are used as a feed supplement for food-producing animals. Their manure is then used to fertilise agricultural fields, meaning resistance genes can be spread to humans through multiple points in the food chain. Direct contact between humans and animals hosting antibiotic-resistant bacteria also adds to the spread. At the community level, people are being over-prescribed antibiotics as a treatment against infections when it may not be appropriate. This allows bacterial specimens with inherent resistance to survive and grow, while others acquire resistance, which then risks being transferred to non-infected individuals.

In the healthcare environment, contaminated objects and hands not properly washed pass on any resistant microorganism present through contact. In emergency care, the tests for bacterial infections may not be fast and reliable enough in life-threatening situations, leading to broad-spectrum antibiotics being prescribed without appropriate diagnostics. According to the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network, microbiological samples were either not taken or remained negative (with no resistant bacteria detected) in many cases of healthcare-associated infections. Lastly, travellers might pick up resistant microorganisms, bring them home and risk spreading these to vulnerable people.

Once resistant bacteria infect a patient, the normal treatment stops being effective. In some cases, access to alternative treatments is not an option.

Alternative treatments can come from new antibiotics. But, unfortunately, the last new class of antibiotics was discovered in the 1980s and the current antibiotic pipeline fails to deliver. Resistance continues to outpace the commercialisation of new drugs. This is partly because new antibiotics tend not to be profitable for pharmaceutical companies since they would most likely be preserved for last-resort treatments.

A no-return point, with antibiotic resistance becoming too widespread, and without antibiotics working, would send us back to the pre-antibiotic era. Infectious diseases will risk more patients’ lives; the ability to safely perform operations or organ transplants will become compromised; infection risks in the immunocompromised, such as those undergoing cancer chemotherapy, will become more severe; and care for preterm infants will become more challenging.

A ‘One Health’ approach, formulated by the World Health Organisation2, proposes to coordinate, mitigate and slow down this multifaceted worldwide crisis. Each country has been advised to adapt these guidelines to fit their political, economical and healthcare national situations.

What are the resistance trends?

An international and collaborative approach is required to mitigate antibiotic resistance propagation. For this, countries must be willing and dedicated to addressing antibiotic resistance at national and international levels.

In Europe, there is a clear north-to-south and west-to-east gradient in the spread of antibiotic resistance, with the Netherlands demonstrating the lowest antibiotic resistance and Greece and Cyprus showing the highest rates (as shown by the ECDC’s yearly surveillance report on antimicrobial resistance in Europe). These geographic differences are tightly linked to antibiotic consumption, with low use being correlated with low resistance levels, and vice versa.

From 2001 onwards, the European Council recommended decreasing antibiotic use, which had a positive effect in countries implementing national programmes. As an example, the Netherlands dropped their antibiotic sales for animal husbandry by 64.5% between 2009 and 2017. British people still consume approximately twice the amount of antibiotics than Dutch people do. Concerning policies in the UK, the government released a 5-year national action plan in 20193, along with a 20-year vision entitled ‘Contained and Controlled’4. The main goals for 2024 are to lower the need for antimicrobials and involuntary exposure, optimise their use and inject more money into innovation, access and supply. This calls for active involvement from public and corporate entities spanning over sectors including human and animal health, agriculture and environment ecosystems. In the longer term, the hope is to minimise transmission, treat resistant infections better, use antibiotics in an optimal fashion and develop new therapies, vaccines, interventions and diagnostics for faster results, better efficiency, and more accuracy.

What can we do?

From a doctor’s point of view, it’s highly recommended to prescribe antibiotics only when needed and to choose broad-spectrum ones as little as possible. Educating patients and making them aware of the importance of complying with the prescription is part of a GP’s role.

From a patient’s perspective, washing your hands properly and often is the best thing you can do to avoid a bacterial infection. Avoid sharing personal items like razors and towels. Rinse fruit and vegetables thoroughly and cook meat products properly. When you’re ill with a bacterial infection, follow your doctor’s prescription; from the dosage to the frequency and the treatment duration.

Characterised as an “invisible pandemic” by the WHO assistant director-general for access to medicines and “a threat to our economic future” by the World Bank, antimicrobial resistance is likely to become the leading cause of death worldwide if we do not improve awareness and change our relationship with antibiotics. Simple habits could help us go a longer and healthier way. Finally, if you are looking to learn more about antibiotic resistance and have some fun, try out Bacteria Combat by Game Doctor, developed by University of Glasgow alumnus Dr Carla Brownnote Games, quizzes5 or the World Health Organisation App67.

References

- www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/how-does-antibiotic-resistance-spread.pdf

- www.wpro.who.int/entity/drug_resistance/resources/global_action_plan_eng.pdf

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/784894/UK_AMR_5_year_national_action_plan.pdf

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/773065/uk-20-year-vision-for-antimicrobial-resistance.pdf

- https://e-bug.eu/world-antibiotic-awareness-week-2019/index.html

- WHO app on Android: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.OneBigRobot.Antibiotics

- WHO app on iOS: https://apps.apple.com/es/app/who-antibiotic-resistance/id1482182807