Is there a fault in our stars?

In China, children with autism are referred to as “Children of the Stars” in an attempt to reduce the stigma surrounding the disorder and to prioritise the improvement of health and well-being of diagnosed children. Indeed, they can be likened to a star because, amidst the darkness they feel inside, children living with the disorder continue to shine with potential. The stigma associated with autism is unique as the disorder is considered to be invisible. For example, a wheelchair is a clear sign of physical disability while there are not always explicit signs that someone has autism; it is therefore difficult for those unaffected by the disorder to understand its symptomatic presentation.

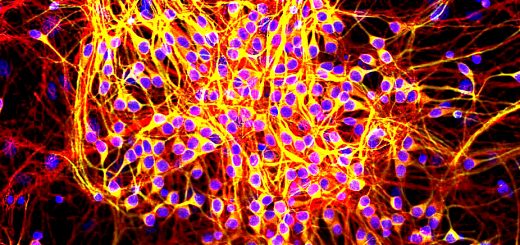

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that includes a range of conditions which are often characterised by a lack of executive functioning, difficulty with social interactions and communication, repetitive behaviours, and sensory sensitivity. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that one in 160 children worldwide has autism1.

When autism research began to accelerate in the early 2000s, many scientists thought finding a cure might become easier. However, the reality was more complicated due to the high cost of research and unique manner in which aetiology and symptom severity vary considerably amongst individuals. This can make it difficult to achieve a diagnosis and design an appropriate treatment plan addressing the specific needs of an individual in the spectrum.

The most problematic issue, however, relates to the ethics of studying children with autism given their vulnerability during the research process, the lack of autonomy in current decision-making frameworks, and the right of affected families to have confidentiality. As such, modern research strives to find ways that help individuals with autism lead healthier and happier lives beyond treating their condition.

Advancements in the field of autism research have contributed largely to understanding the genetic basis of autism as well as the discovery of pharmacological interventions, such as folinic acid and oxytocin, that are effective in easing symptoms2.

One example is the work of Professors Adrian Bird and Huda Zoghbi who discovered the role of the MECP2 gene in Rett syndrome, an autism spectrum disorder, proving that neurodevelopmental disorders are reversible3. Despite these significant advancements, there is still no universal cure for neurodevelopmental disorders including autism.

This leads one to ask: do we truly need a cure for autism? The term “neurodiversity” was coined in 1998 by an autistic Australian sociologist, Judy Singer. She describes it as a unique approach to learning and disability arguing that diverse neurological conditions are simply the result of normal variations in the human genome. Interestingly, the Neurodiversity Movement originated from the Autistic Rights Movement; at the annual meeting of the International Society for Autism Research (INSAR) in Montreal, Canada in May 2019, one divisive topic widely debated was the concept of neurodiversity4.

The notion of neurodiversity is often likened to the more familiar concept of biodiversity and is very compatible with the civil rights plea for minorities to be accorded with dignity and acceptance, and not to be pathologised.

Looking at autism within the scope of neurodiversity is not without ethical issues, however, as there are instances in which the movement can cause pressure and misrepresentation – particularly as media outlets have tendencies to represent those with autism as ‘geniuses’ or ‘savants’. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the media can be powerful tools for communicating validated facts and addressing ethical issues, such as whether or not autism should be defined as a disorder or classified as an impairment. Additionally, the media can significantly influence the behaviour of people with autism in seeking appropriate medical treatments or therapy by presenting facts supported by rigorous research and scientific findings.

Those who embrace neurodiversity would argue that autism should not be defined as a disorder but rather a ‘difference’ because people with autism often excel in their attention to detail, perfectionism, drive, and focus. On the other hand, it may favour the high-functioning individuals with autism (HFA) and overlook those who struggle with severe autism, thus undermining the ability of those with autism to obtain appropriate medical treatment. In this case, those with autism might have a higher tendency to reject biomedical treatment as well as applied behavioural analysis (ABA), a specific kind of therapy for autism to improve attention, social skills, and memory5.

Importantly, the biomedical aspect of autism recognises that autism is implicated with physiological and metabolic abnormalities, and seeking biomedical treatment is of vital importance for individuals with autism to reduce harmful symptoms that negatively impact their quality of life.

Recognizing the principle of neurodiversity does not negate the validity or necessity of treatment nor does it imply that these medical treatments should not be fully funded and supported. Rather, acknowledging neurodiversity suggests the importance of being mindful about the goals of biomedical interventions and highly individualistic nature of autism when considering which treatments to pursue. Recognising our rights to equality and non-discrimination will serve as the foundation of diversity and inclusion, given no one should have constrained opportunities because of the way they were born or the presence of a disability.

Can you imagine a world in which autism and other disabilities are accepted by society, whilst medical treatment is simultaneously available to complement such social acceptance? Perhaps striking a balance between the biomedical view of autism and the unique lens of neurodiversity is the ideal way to optimize the quality of life for those living with autism. It’s time to give endless support to those with neurodevelopmental disorders, like autism, so they can regain their confidence, become empowered, and embrace who they are. After all, is there truly a fault in our stars?

This article was specialist edited by Aditi Desai and copy-edited by Dzachary Zainudden

References

- https://autismwales.org/en/community-services/i-work-with-children-in-health-social-care/the-birthday-party/

- https://www.autismspeaks.org/science-news/top-10-autism-studies-2019

- https://www.lundbeckfonden.com/en/mapping-of-a-rare-brain-disorder-in-babies-leads-to-award-of-the-brain-prize-2020/

- https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/the-concept-of-neurodiversity-is-dividing-the-autism-community/

- https://www.mayinstitute.org/about/aba.html

This is a wonderful piece. This shows the bigger spectrum of what autism is and see it in a different light. The information shared can help families ponder on the best care and help they can provide for their children.