Sowing the seeds for the plantibiotic revolution; the journey towards greener pesticides

It’s the best time of year in the UK: it’s strawberry season! Nothing is more quintessentially British than tucking into some strawberries and cream while watching Wimbledon. But before you can tuck into those strawberries grown by some guy called Angus in Perth, they need a quick wash under the tap. Have you ever wondered why? In 2017 a governmental committee which deals with pesticide residues in food reported that some strawberry growers were using up to 16 different pesticides (although this was incredibly variable1 ).

Pesticides are chemicals that aim to control pests from crops. They can be sprayed to treat mould infections, bacterial infections and insect infestations. If we didn’t use pesticides, we would be pretty-much throwing 1/3rd of the crop yield away before we’ve even started growing them in the field2. If we didn’t have pesticides then there would be no bananas3, as all of the bananas you get in the shops are of one variety (cavendish) and are unable to effectively fight off diseases.

The pests we want to fight off normally eat the leaves and fruit of the crops, reducing the yield a farmer can get from their crops. This impacts crop quality — after all, who wants a rotten, mouldy, half-eaten, larvae-infested strawberry? Nobody. So pesticides are clearly useful to us, and they allow everyone to enjoy food at relatively cheap prices. If all pesticides were banned tomorrow it would cost farmers a small fortune to get a good yield to sell to supermarkets and consumers. This would obviously make everything we buy more expensive; otherwise, would the farmer bother growing something that is going to lose them money?

However, these pesticides, if used excessively, can have a negative impact on the environment and human health. For example, streptomycin can cause massive disruption to natural ecosystems and can encourage bacteria to develop antibiotic resistance4. The Trump administration has repeatedly given the green light for farmers to spray 1.6 million pounds of medically relevant oxytetracycline and streptomycin on citrus trees in Florida every year5.

The reason this is bad is that it can encourage bacteria to become resistant to antibiotics. This antibiotic resistance in the food chain can then spread into human health because bacterial communities talk to each other and share characteristics that help them survive and thrive in challenging environments. Considering the desperate need for antibiotics, we need to reduce this type of practice and only use them as a last resort. Otherwise, we won’t be able to treat people in the hospital for basic infections. To add insult to injury, antibiotic overuse may be the cause of the decline in the bee populations, as over-reliance on pesticides is weakening bee health, and reducing natural pollination. This understandably changes our environment and affects crops that rely on bee pollination, like the humble avocado6.

One alternative to using pesticides is to vaccinate crops. Vaccinating crops normally involves genetically inoculating plants to make them resistant to disease, so it’s not too dissimilar from vaccinating humans. Genetic inoculation, also known as genetic modification (GM), is often a misunderstood concept which people tend to over-complicate. The aim of GM in crops is to improve their functionality. It can make crops more resistant to disease, improve the nutritional value or make them more sturdy in tough environmental conditions like drought. In a way, it is similar to downloading an app onto your smartphone. If you download the YouTube app onto your phone it enhances the “user experience” as you can now watch heartwarming cat videos. At the University of Glasgow, researchers have developed a biological “app” in plants called ‘Plantibiotics’.

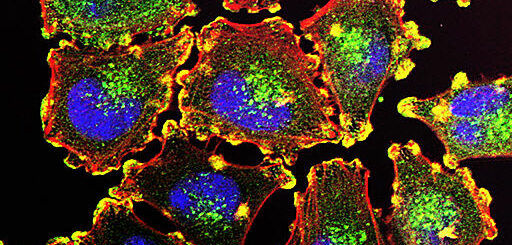

‘Plantibiotics’ are small protein antibiotics (also known as bacteriocins) that are produced by naturally-occurring bacteria and have the ability to kill unwanted bacterial diseases in plants. These bacteriocins are very specific so they can be harnessed to kill the bad bacteria and maintain healthy populations of beneficial bacteria. Bacteriocins are produced by all the major bacterial species we come into contact with, especially bacteria which are important for gut health. Weegie researchers have genetically inoculated plants (cress and tobacco) with a bacteriocin called putidacin L1, a well-studied bacteriocin that is toxic to Pseudomonas syringae — one of the bad boys in plant disease world. The researchers were able to show that putidacin L1 was able to provide robust protection against P. syringae after flooding plants with high concentrations of bacteria7.

This has obviously been all done in the lab and not the real world, so the next stage would be to test this in the fields. However, there are positive vibes coming from these researchers as they believe that expanding and deploying the plantibiotic repertoire can be an important step towards reducing chemical spraying onto crops. This means our food will contain fewer pesticides and could be an important step in helping to retard the rapid decline of the global bee populations.

This article was specialist edited by Emily May Armstrong and copy-edited by Kirstin Leslie.

References

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/726926/expert-committee-pesticide-residues-food-annual-report-2017.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261219403002540

- https://croplife-r9qnrxt3qxgjra4.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/pdf_files/Without-Fungicides-World-Banana-Exports-Would-Collapse.pdf

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-00878-4

- https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/press_releases/2018/oxytetracycline-12-06-2018.php

- https://www.panna.org/food-farming-derailed/bees-crisis

- https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/649178v1

I found something similar a few weeks before, but you did detailed

study, and your article appears to be more compelling than the others.

I am amazed by the arguments you provided as well as the fashion of your post.

I enjoy when posts are both informative and interesting,

when even dull facts are presented in an interactive manner.

Well, it’s surely on your article.