Limits to collaboration?

We are intrinsically social creatures. Rooted deeply in our culture is collaboration: a key to survival and sustaining our society. In turn, it is only natural that teamwork is a highly valued and sought-after skill in any job description and, therefore, a skill we have to develop from an early age. In order to collaborate efficiently and work together with others, we learn to adapt our personal views and conform within groups and society.

Conformity is often seen as a beneficial factor. Norms and rules have been refined by decades of common opinions and beliefs and are, in a sense, the common ground for all people who are a part of this big collaboration we call society. However, it can also have a negative impact on individuality. Therefore, the notion of conformity has mixed valence, which is why it has formed an area of research interest for almost 70 years.

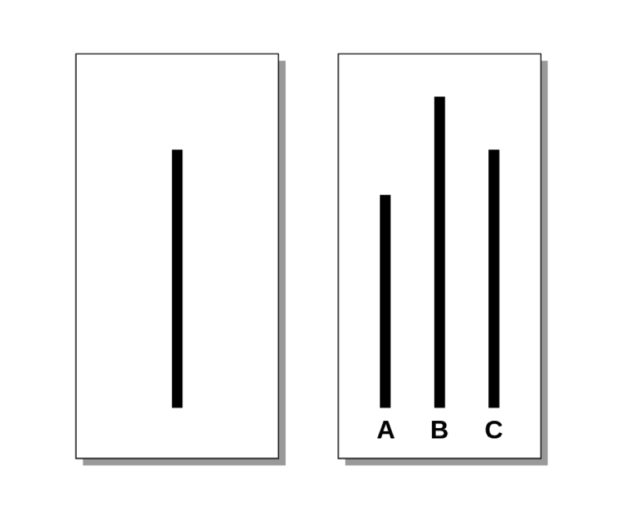

Early on, a series of conformity experiments highlighted the power of the group. The first of its kind was conducted in 1951 by Solomon Asch, a pioneer in social psychology who showed that people are prone to follow the lead of others and, consequently, respond incorrectly to a simple task, such as judging the length of a line (Figure 1). In the experiment, a real participant was told to be surrounded by seven other participants who were, in fact, a group of actors. When actors gave out loud the wrong answer, participants gave the same wrong answer 36.8% of the time, demonstrating people are, to a certain degree, predisposed to conform. In contrast, in the control group participants were not exposed to others’ answers, and the error rate was less than 1%. Many factors such as personality type, self-esteem, confidence or even amount of attention given to the task come into play to explain such a drastic difference. But, regardless of the reason, this phenomenon shows we don’t always trust our own rationality if it does not coincide with the general opinion.

Data from multiple trials show approximately 75% of participants would follow the group response and give at least one wrong answer, demonstrating our susceptibility to be influenced by others1. Similarly, the ‘smoke filled room’ experiment shows that people conform even in situations possibly presenting a threat to their health. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire while smoke started to fill the room. If alone in the room, the majority of the participants reacted by leaving the room and reporting the incident within 2 minutes. If two other fake participants were present in the room and calmly ignored the smoke, the probability of the real participant to report the incident would drop to 10%2.

One of the most shocking and famous experiments testing the limits of obedience is still the 1961 Milgram experiment3. Influenced by the Holocaust and how such an event occurred in a modern society, Stanley Milgram, a psychologist at Yale University, was determined to recreate a situation in which normal people would succumb to blindly follow orders. He designed a study in which he tested the susceptibility of regular people to give electrical shocks to others if instructed so. The real participant was told he was only there to assist in a psychology task testing memory and learning abilities of someone else (in fact an actor). They were instructed to give increasing electrical shock stimulation (which were fake, without their knowledge) with every error made by the fake subject. The initial belief of both psychology major senior students and Milgram’s fellow professors was that his experiment would be a complete failure. In fact, 65% of the participants knowingly administered a potentially lethal 450-Volt shock , and all administered shocks of at least 300 Volts despite visibly showing discomfort in performing the task.

Many recreations and variations of this study have been conducted, and it is now believed that this obedience depends on the level of trust given to the expert instructing the electrical shocks. This has its roots in the learned conformity in the face of a trustworthy authoritative figure. It is also important to note that this experiment raised a number of important ethical considerations about the level of deception and emotional stress that a participant should be subjected to, especially without any informed consent. Nevertheless, the results obtained remain extremely powerful to this day. All the experiments mentioned created an artificial setting that tests confidence, challenges personal beliefs to the limit, and questions peoples’ interactions in a society. But in real life, what is the extent to this conformity and how does this relate to collaboration?

Different cultures are thought to differ in this sense. It is generally accepted that Western countries, such as Canada or the United States, are more individualistic, while Eastern countries, such as China, India, or Japan, are more collectivistic in their nature. The society you are brought up in can shape your values and perceptions, from friends and family to the education system. Individualists are more autonomous and value personal achievement and freedom, while collectivists are more defined by their social context and value group goals and conformity. The first would normally create competition between members while the latter would rather lead to collaboration. Which approach is best? There is no right or wrong answer. Both competition and collaboration can lead to achievements if implemented properly. Also, on a more personal level, problems occur in both types of societies; people in individualistic cultures are susceptible to loneliness, while people in collectivistic cultures may develop a strong fear of rejection4. Therefore, although a person cannot be categorised as purely a collectivist or individualist (rather, these traits lie on a spectrum), it is important to note how culture and common views held by the majority, influence the way one relates to self and others.

Both at the level of society and of individuals, the ability to collaborate and make independent decisions have to coexist to achieve outstanding results. When it comes to conformity, there are both benefits and limitations, as suggested by various psychological experiments. Understanding the dynamics of different types of cultures has much to offer. Incorporating both individualistic and collectivistic values could help adapt our strategy to different problems accordingly and benefit us personally and as a society.

This article was specialist edited by Kirstin Leslie and copy-edited by Sonya Frazier.

References

- Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership and men; research in human relations (pp. 177-190). Oxford, England: Carnegie Press.

- Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group Inhibition of Bystander Intervention in Emergencies. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 10(3), 215–221.

- Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral Study of obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4), 371-378. Also, the movie ‘Experimenter’ released in 2015 follows the story of the Milgram experiment

- Gorodnichenko Y., Roland G. (2012) Understanding the Individualism-Collectivism Cleavage and Its Effects: Lessons from Cultural Psychology. In: Aoki M., Kuran T., Roland G. (eds) Institutions and Comparative Economic Development. International Economic Association Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London

1 Response

[…] widely agreed that not all scientists wear white coats and work in labs. But, as highlighted in a previous theGIST article, human beings often behave the same as those around them. When it comes to science, if we really do […]