Fact or fallacy? The text neck “epidemic”

‘Text neck’ is an unscientific term coined to medicalise associated discomfort with prolonged forward bending of the cervical spine, your neck, when using a mobile device. The phrase seems somewhat comical and makes me wonder why my grandparents never told me of the ‘newspaper neck’ epidemic in their day, or why Mr. Wilson, my secondary school history teacher, omitted the infamous scroll reading ache that plagued Greek scholars around 500 B.C.

A brief read of Dr. Google’s top ten hits can simplify the explanation for text neck as:

1) the use of mobile devices has increased massively in the last two decades.

2) the typical increased forward bending of the head when using a device can increase forces acting on the neck

3) the neck is not strong enough to withstand these forces leading to injury

4) neck pain is therefore associated with ‘poor’ neck posture.

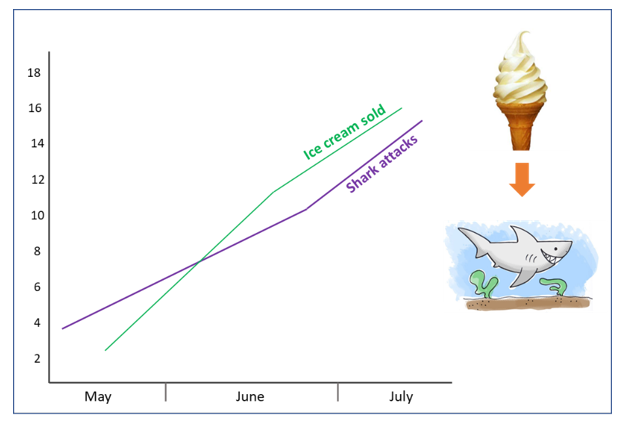

On the surface this comparison might not seem all that silly, however similar correlations can be made to prove nearly any concept: such as increasing ice cream sales correlating with an increase in shark attacks1! Okay, I may be stretching a bit far with that example, so if that is not enough to raise the skeptic in you: a five-year long study2 did not find an association over time with phone use and lasting neck pain, nor did a more recent study3 in 18 to 21 year olds.

From my own observations, ‘text neck’ appeared on my social media feed in 2015. The various infographics and health posts followed the publication of a study4, which suggested that flexing the neck far forward can place up to 60 lbs of force on the cervical spine. This is roughly the same as having the weight of a slightly tubby miniature dachshund sitting on the back of your head. Shock, horror!

Biomechanics researcher Dr. Greg Lehman5 criticized this paper, claiming among other valid omissions, it did not specify what the force is acting upon. Those of you familiar with high school physics will recall that a force, in this case the effect of gravity acting upon the weight of the head, requires direction as well as magnitude. While I acknowledge biomechanics is more complex than this, I am applying the same reasoning of this study’s conclusions to say: do not fear the force young Jedi, as the cervical spine structures can withstand around 450 lbs of it6.

Additionally, the premise of this argument assumes the body is not adaptable, and is a fragile or finite material which is worn away. This is untrue, as we know lifting weights or performing exercise increases muscle size and strength, or holding the ‘plank’ exercise for progressively increased time improves your muscle endurance. The examples of adaptability and resilience in our own body are vast: bone density is improved with weight bearing exercise for those with osteoporosis, or ‘brittle bones’. Even recreational runners who pound their joints repetitively during jogging have less arthritis in their knees compared to non-runners7. You might even consider the body somewhat ‘anti-fragile’.

On the opposite side of this logic, a lack of force can be problematic. Astronauts who are subjected to a period of time without gravity and its associated forces weaken their bones, muscles and joints. They require regular resistance training to place sufficient forces on their body, and a gradual increase in both activity and strengthening upon return to earth to prevent injury. Our body adapts both ways with force.

Will leaving your head bent forward for a prolonged period of time contribute to discomfort? Yes, it could, but so would holding a plank exercise for five minutes without training. If we glance at fear-inducing newspaper headlines, or take advice from ill-informed people (with good intentions) that suggest we should be concerned with these aches, often we fixate on them and increase their presence and how they affect our day to day living. You could argue that changing position when feeling an ache, and resistance exercise for the surrounding muscles are ways of sensibly building up tolerance and relieving discomfort, rather than devoting time, energy and concern to avoiding a range of motion naturally permitted by our necks.

So how should we hold our head when not moving? There is no scientific consensus on what a perfect posture is. Even if we did know, holding a different posture for prolonged periods of time can be more difficult, due to increasing effort on under-used muscles, alongside concentration to maintain the position. This is again complicated as we fidget and move through a natural range of movements. Do we ever sit truly still? Perhaps we should let our comfort guide us.

A change of position can be helpful when we get an ache, but that movement and variance is more relevant than the seemingly unattainable ‘perfect’ neck posture. Where a change of position relieves your symptoms, it is incorrect to assume that because pain relief followed posture change, that a certain position uniformly causes pain. Moreover, structural changes in the spine8 and the neck9 are poorly related to pain, and we know that pain is literally defined as a complex sensory and emotional experience10. Thereby, equating it to posture and force alone is somewhat reductionist, and at worse, an inaccurate and potentially harmful message11 for the public.

Considering all this evidence, perhaps the only danger ‘text neck’ ever posed was to the blood pressure of any scientifically literate healthcare professional who was asked about it.

This article was specialist edited by Mollie Wilson and copy-edited by Emily May Armstrong.

References

- https://the-gist.org/2018/11/shark-attacks-ice-creams-and-the-randomised-trial/

- Gustafsson, E., Thomée, S., Grimby-Ekman, A. and Hagberg, M., 2017. Texting on mobile phones and musculoskeletal disorders in young adults: a five-year cohort study. Applied ergonomics, 58, pp.208-214.

- Damasceno, G.M., Ferreira, A.S., Nogueira, L.A.C., Reis, F.J.J., Andrade, I.C.S. and Meziat-Filho, N., 2018. Text neck and neck pain in 18–21-year-old young adults. European Spine Journal, 27(6), pp.1249-1254.

- Hansraj, K.K., 2014. Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surg Technol Int, 25(25), pp.277-9.

- Greg Lehman. 2014. Text Neck is Bad Science and Fear Mongering. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.greglehman.ca/blog/2014/11/22/text-neck-is-bad-science-and-fear-mongering.

- Przybyla, A.S., Skrzypiec, D., Pollintine, P., Dolan, P. and Adams, M.A., 2007. Strength of the cervical spine in compression and bending. Spine, 32(15), pp.1612-1620.

- Alentorn-Geli, E., Samuelsson, K., Musahl, V., Green, C.L., Bhandari, M. and Karlsson, J., 2017. The association of recreational and competitive running with hip and knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 47(6), pp.373-390.

- Heredia-Rizo, A.M., Petersen, K.K., Madeleine, P. and Arendt-Nielsen, L., 2019. Clinical Outcomes and Central Pain Mechanisms are Improved After Upper Trapezius Eccentric Training in Female Computer Users With Chronic Neck/Shoulder Pain. The Clinical journal of pain, 35(1), pp.65-76.

- Grob, D., Frauenfelder, H. and Mannion, A.F., 2007. The association between cervical spine curvature and neck pain. European Spine Journal, 16(5), pp.669-678

- International Association for the Study of Pain, 2009. Terminology and taxonomy. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698

- Darlow, B., Dowell, A., Baxter, G.D., Mathieson, F., Perry, M. and Dean, S., 2013. The enduring impact of what clinicians say to people with low back pain. The Annals of Family Medicine, 11(6), pp.527-534.