The Bright Future of Nuclear Power

The history of civilian nuclear power started with a schism between two very different philosophies. Should the neutrons from the splitting of the atom be slowed down, or be allowed to travel at unimaginable speeds? This initial battle was won by the Light Water Reactor (LWR) family of reactors, which use thermal (slowed) neutrons, and they remain the status quo to this day.

Why did LWRs come out victorious? A number of different factors have contributed to ensuring their dominant position. During the early days of nuclear power, they were regarded to be simpler and cheaper to build, operate and maintain. This was of particular interest to one of the key actors in the story of nuclear power – the U.S. Navy. LWRs were well suited for use in submarines and the admiral leading the Navy’s work also oversaw the Shippingport project (the world’s first, full-scale nuclear power station), which had a significant impact on the choice of reactor type. Further to this, whilst uranium was initially believed to be a very scarce resource, exploration showed this not to be the case. This undermined one of the main arguments for fast reactors at the time, and the industry subsequently chose LWRs, which are simpler, but less efficient.

LWRs use water as a moderator which slows down the neutrons to sustain a further chain reactor. The most common LWR reactors are Pressurised Water Reactors (PWRs) and Boiling Water Reactors (BWRs) which both operate in a pressurised environment. In a fast reactor on the other hand the reactor core and fuel composition is designed in order to allow chain reactions to be sustained with more energetic neutrons. Moderators are thus no longer needed and the reactor core becomes more compact as a result. The coolant in fast reactors does not have to moderate the neutron as it does in LWRs, allowing different materials that are better at removing heat to be used, such as liquid metals.

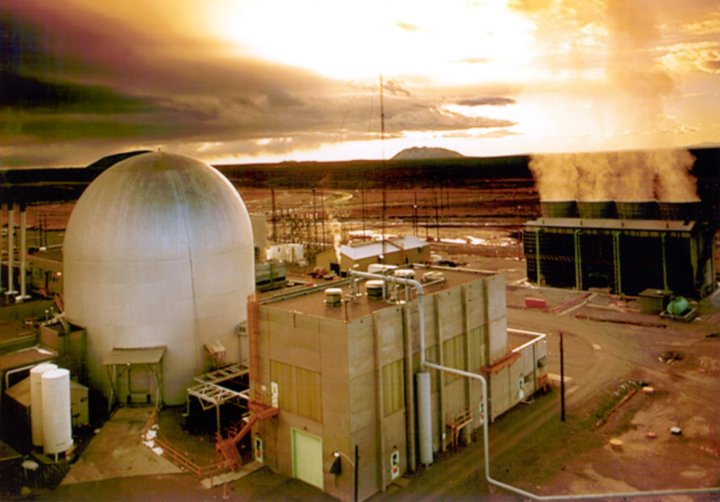

At the Argonne National Laboratory, fast reactors were extensively researched. Whilst the first Experimental Breeder Reactor (EBR-I) resulted in a meltdown, the EBR-II reactor ran successfully for over 30 years until the Clinton administration defunded the project. EBR-III was meant to be the first commercial fast reactor, but was axed as well. One important lesson however was drawn from this defeat – the Integral Fast Reactor (IFR) concept works. Fast reactor research has been constantly starved of research funding, but a few bright spots can still be found.

The Experimental Breeder Reactor-II, Argonne National Laboratory (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/ba/EBRII_1.jpg)

The Soviet Union, and subsequently the Russian Federation, has long been a research stronghold for nuclear. Whilst most of us are likely to associate the Soviet Union with extremely risky experiments and a lax security mentality – Chernobyl being the prime example – Russia is currently leading the world in fast reactor development. So why is this concept interesting? When compared to conventional nuclear power, the IFR concept is superiorly efficient. IFRs achieve a burn-up rate around 99-99.5%, which should be compared to approximately 1-3% in commercial Light Water Reactor (LWR) designs. Further to this, the design of IFRs ensures that they are highly proliferation resistant. This is connected with the move away from the conventional thermal reactors we are accustomed to and is shifting focus towards the fast spectrum, which leads to a radical change in the core’s fissionability.

With moderated, slowed down neutrons, only a fraction of the nuclei in the core can be fissioned. With unmoderated, or fast neutrons, a considerably higher proportion of the nuclei are fissionable. This leads to favourable recycling properties which present a solution to the single biggest issue concerning commercial nuclear power – waste.

The supremacy of LWR technology has led to some unexpected problems. When the idea of a plutonium economy was scrapped in the 1970s and 1980s the nuclear fuel cycle was left wide open. This has resulted in the absurd situation where the vast majority of nuclear fuel is unused, thanks to the ‘once-through’ fuel cycle doctrine. This means that fuel assemblies are run through the reactor once, before being disposed of, and in the process creating vast stockpiles of nuclear material. By not reprocessing, only about 1-3% of the energy content of the fuel is used. However, as soon as plutonium is involved the fears of proliferation are never far away. This fear is closely connected with any reprocessing of nuclear fuel, a process that currently is shunned for mainly political reasons.

The proliferation concerns are mainly associated with LWRs where it is relatively simple to separate the plutonium from the used fuel assemblies, but the very nature and design of the IFR concept adequately addresses these concerns. Once in operation the core of the fast spectrum reactors become very radioactive, thanks to increased activation due to the fast neutrons. Whilst enriched U-235 or Pu-239 can be handled with gloves, the IFR plutonium will be laden with actinides and other highly radioactive elements. The reprocessing of fuel assemblies in an IFR is on-site and due to its intense radioactivity subject to remote handling only, before being reinserted into the reactor. This gives extra layers of proliferation resilience to the reactor and largely removes the risk of any unauthorised diversion of fuel or waste.

Fuel composition before and after one cycle in LWR (http://hamaoka.chuden.jp/english/resource/n-power/cycle_img_01.gif

When the neutrons are not slowed down the amount of fuel in the reactor increases. With fast reactors, by-products from conventional nuclear power plants can be used as well as material from decommissioned nuclear weapons. Additionally, the fertile U-238 that makes up the bulk of the fuel can be converted into plutonium which subsequently can be used as fuel. This makes the reactor a breeder (i.e. more fuel is created than burned). IFRs therefore allow us to, in an efficient manner, deal with our nuclear waste legacy whilst generating carbon neutral energy rather than just hiding it underground. They also greatly increase the amount of available fuel for nuclear fission by ensuring that the vast majority of uranium (U-238), making up approximately 99.3% of all uranium, can be used for energy production.

All taken into consideration, the IFR and fast reactor concepts present an exciting future for nuclear fission. With their making use of the full potential of uranium, waste recycling and proliferation resistance, they hold the potential for truly revolutionising changes to nuclear power. LWRs and IFR reactors are likely to co-exist in the future, thus ensuring that mankind has a reliable and entirely safe carbon-neutral electricity source. By opting to commercialise fast reactor concepts we make sure that future generations will not have to deal with our nuclear legacy for countless generations. By submitting to our irrational fears over nuclear energy we are removing our best chance at combating the catastrophic climate change we face. It is time to challenge the myth, the lies and the misconceptions around nuclear power. If we do, the future of not only nuclear power, but mankind, is indeed bright.

This article was specialist edited by Derek Connor and copy edited by Sarah Neidler