Where’s the lettuce? Food, Brexit and Climate Change

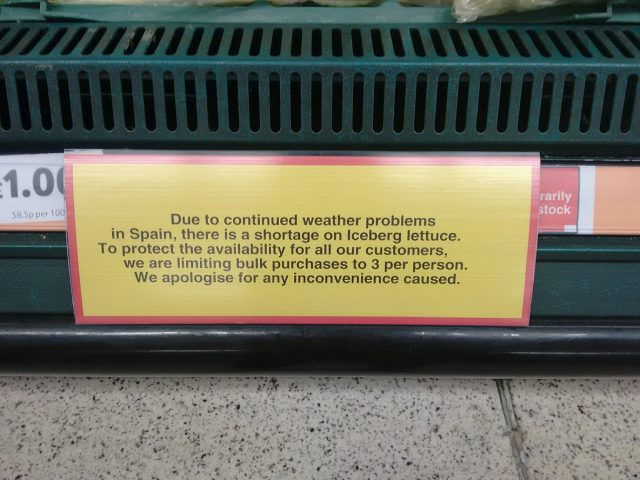

Have you ever thought about the journey that your food makes on its way to your plate? Lettuce rationing is just the tip of the iceberg, as of the 2nd February 2017, supermarkets UK-wide started limiting bulk-buys of our favourite brassicas. Why? Surely we’re able to grow these hardy vegetables even in our terrible British weather? Climate change has struck again, and this time it’s hinting towards potential disaster for a food the UK loves. Some supermarkets have even resorted to flying in our leafy greens from far-flung fields in the US.

How sustainable is this importing practice, and do we need to address our reliance on imports? The UN defines food security as persons having ‘access to sustainable, nutritional, accessible, and affordable food’, regardless of country. Broccoli and aubergines may tick the boxes for clean eating, but if we’re so reliant on importing them, do they tick the other boxes, and is their production environmentally clean? Clearly, we’re not facing famine conditions, but how robust is our food network, and how will Brexit impact it?

Where does our food come from?

In 2015, the UK only grew 52% of its food, importing 29% from the European Union — predominantly fruit and vegetables out of season1. Conversely, our biggest exports are chocolate, cheese, and salmon, propping up our £18 billion food and agricultural produce export industry to the EU. Robust trade networks are essential for any economically developed country, but ours is failing us. The UK relies on cheap labour in other EU countries to keep our plates full, and as of 2016, we were only 61% self-sufficient. What’s more, if food production in the UK was to stop today, we would only have 3 to 5 days’ worth of food stockpiled2.

It’s no secret that food prices and global oil prices are intrinsically linked: wheat and oil prices rise and fall together, and rises in total food prices in recent years have been directly attributed to the start of the 2011 Arab Spring Uprising 3. With a highly complex and interconnected trans-national food, fuel, and import network, there’s only one factor big enough to bring the whole thing crashing down to its knees — the climate.

Can we blame climate change?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts devastating changes to global temperature, rainfall, desertification, available arable land and an unprecedented rise in global atmospheric carbon dioxide levels by 2067. We tipped over the 400 parts per million mark in September 2016: the highest level of CO2 in 4 million years. Although global temperatures are rising, this doesn’t directly translate to hotter, drier weather. In 2015, the UK experienced the hottest and wettest December since records began and the entire winter of 2015 was recorded as the second wettest and the third warmest ever in the UK 4

Murcia, southern Spain — where we import the majority of our leafy greens, broccoli, aubergines and courgettes from — has been hit incredibly hard. Some farmers have lost up to 100% of their crop. Supply and demand has kicked in. In some cases, food prices rose by 300%; this is a curse for consumers and farmers alike5.

Can we definitively blame climate change for the vegetable-destroying deluge in Spain? The latest extreme weather is too recent to be properly investigated in reliable scientific journals, but the IPCC had already singled out southern Spain as a potential extreme flash flooding victim as early as the 1980’s6. Extreme weather fluctuations are only set to continue, causing severe and often unpredictable changes globally. Higher temperatures and reduced water supply will reduce total crop yield and increase prices of staple foods. Calorie intake in at-risk areas will be compromised, as increased climate variability reduces food supply stability.

Picture of sign in Tesco. Credit: Emily May Armstrong (author)

Will leaving the European single market affect our food?

So as of summer 2017 we seem to have mostly recovered from our lettuce drought, but what happens when we leave the European single market? Could this impact food imports in the future? The majority of our food imports come from EU sources, especially out of season. The EU is responsible for setting our stringent food safety standards, and food products are able to move freely within the EU, however, food imported from third party countries is subject to extreme scrutiny. Brexit may make it much harder to export food produce to the EU, losing vital capital in the process. Equally, this is sending food prices skyrocketing for UK consumers as a consequence. On the 7th March, the Guardian revealed that supermarket inflation has driven the cost of tea up by 6%, butter by 15.8% and fresh fruit by 4.2%, according to statistics gathered by market researcher Kantar7.

Going beyond the EU and importing foods from further-flung fields will cost more overall; the expensive transport costs will counter any savings made from potentially cheaper labour. Furthermore, all this added food movement will require massive additional consumption of fossil fuels, emitting even more CO2 into our atmosphere: exactly the opposite of what our climate needs. We may also end up trading with countries that are already more food-insecure than the UK, potentially opening up exploitative practices outlawed within the EU. These can include inhumane working conditions, child-labour, and ‘poverty-pay’. Is the UK ready to broker these deals properly? Can we be assured our food is produced ethically, whilst still being able to afford it?

What can we do?

As UK food consumers, what can we do to combat climate change and the potential loss of our food trading partners? One option is that we start growing our own food, in our own homes. Even people pressed for outside space can start cultivating greens and veggies in the comfort of their kitchens using nifty and affordable home cultivation set-ups. Alternatively, allotments and community gardening projects can help you get your green fingers growing. You can also concentrate on buying locally sourced produce, which is often cheaper than relying on big supermarkets.

Another option is to look at food wastage: figures released by WRAP, a UK food waste monitoring group, estimate that we throw away 10 million tonnes of food each year, costing us as a nation over £17 billion annually8. There are, however, some non governmental options to help combat this wastage. New ‘waste’ online supermarket ‘OLIO’ means you can share food with others9, and food writer Jack Monroe has a brilliant guide on how to save food10. These changes might mean waving goodbye to lemons in winter, but it’ll improve your food literacy and help protect our fragile planet and maybe even us from another food shortage next winter.

This article was specialist edited by Richard Murchie and copy edited by Barry Robertson.

References

- https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/553390/foodpocketbook-2016report-rev-15sep16.pdf

- UK’s food stockpile https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/515048/food-farming-stats-release-07apr16.pdf

- Arab Spring Uprising http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00263206.2013.850076?src=recsys&

- http://www.usatoday.com/story/weather/2016/01/20/earths-warmest-year-record-global-warming/79051806/

- Lettuce rationing https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/feb/03/tip-of-the-iceberg-lettuce-rationing-broadens-to-broccoli-and-cabbage

- IPCC Phenological data http://www.uco.es/aerobiologia/publicaciones/phenology/phenology-aero/garcia_mozo_phenological_2010.pdf

- Market Research by Kantar https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/mar/07/food-inflation-doubles-uk-shoppers-feel-pinch market researcher Kantar

- Food wastage statistics http://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Estimates_%20in_the_UK_Jan17.pdf

- https://olioex.com/

- https://cookingonabootstrap.com/2016/02/08/dont-throw-that-away-an-a-z-of-leftovers-tired-veg-etc-and-what-to-do-with-them/