Virus, virus shining bright

In 2019, the overall top trending search on Google in the United Kingdom was “Rugby World Cup”. There are no prizes for guessing what the top search of 2020 was: “Coronavirus”. From “How to watch the Champions League Final?” to “How to make a face mask?”, in the space of a year the COVID-19 pandemic changed our entire way of life. Coronavirus was quickly adopted as a name for the virus responsible for COVID-19 illness, SARS-CoV-2. However, it actually encompasses a family of viruses of which currently seven of its members are known to infect humans.1

The coronavirus family was first identified in 1964 by June Almeida, a Scottish scientist whose work received renewed recognition during the COVID-19 outbreak. However, this discovery was only one of many important contributions she made to the field of virology during her remarkable career in which she published no less than 103 scientific papers2. Although her work gained her an international reputation within her field, like many women in science, her contributions are not widely known by those outside it.

Born in Glasgow in 1930, June Hart was the daughter of a shop assistant and a bus driver. She excelled at school, particularly in science, earning the Whitehall School science prize. However, she left school at the age of 16 and did not attend university as her family lacked the financial means to support her education. Instead, she secured an apprenticeship as a lab technician in the histopathology department of the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. Here, she combined her passion for photography with science by using microscopes to investigate samples for signs of disease or infection.3

At the age of 22, Hart moved to London with her parents and continued work as a lab technician at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. She met her first husband, Enrique Almeida, and in 1956, they moved to Canada. Although Almeida did not know it at the time, this move to Canada would be key to her career as an eminent virologist. Now a skilled light microscopist, Almeida took up a position at the Toronto Cancer Institute as an electron microscopist, something which she had no experience in.

The electron microscope, invented in the 1930s, was a relatively new technology at the time. In contrast to a standard light microscope in which light is shone through a sample and viewed through magnifying lenses, an electron microscope uses a beam of electrons to build an image of the sample on a photographic plate. Due to electrons having a shorter wavelength than light, electron microscopy creates a higher resolution image, allowing the study of incredibly small biological structures such as viruses and bacteria.4

The detail in the image is further enhanced if a negative staining technique is used to increase the contrast between the sample and the background. For this, a heavy metal such as phosphotungstic acid is added to the sample; few electrons pass through the regions of the sample stained with the heavy metal, resulting in lower photographic exposure and increased contrast of the image. This allows more intricate structures to be seen clearly. It may sound simple but capturing images of something as tiny, delicate, and intricate as a virus requires painstakingly precise preparation of the sample from start to finish.

Alongside her colleagues at the Toronto Cancer Institute, Almeida used negative staining to increase the understanding of the role certain viruses play in the development of cancer. Excelling at electron microscopy, Almeida pursued research on the molecular structure of viruses, noting that their shape, size, and structure (known as morphology) could be used to classify viruses sharing common features into families. She published her proposed classification system in 1963.5

Almeida then began to use a lesser-known technique called immune electron microscopy (IEM). Antibodies specific to the virus were used to clump viruses together, forming groups that were easier to identify amongst the background of cells and proteins present in the sample. IEM allowed for better visualisation of viral interactions with immune cells and required fewer preparation steps than negative staining, reducing the chances of damage to the delicate specimens before imaging. Almeida successfully used this technique to visualise polyoma viruses which can cause various cancers.

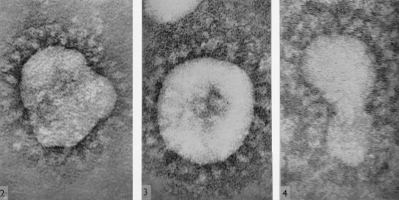

Image by June D. Almeida and D. A. J. Tyrrell (WikiCommons)

Following a move back to London with her daughter, Almeida began working at St Thomas’ Hospital Medical School. Having gained a reputation as a leading expert in viral imaging, she was tasked with imaging an unknown virus that researchers investigating the common cold were struggling to identify. Her images showed a virus that looked similar to influenza but had distinct protrusions on its outer surface, giving the effect of a halo surrounding it. Almeida and her collaborators realised they had photographed a new type of virus and decided to name it a “coronavirus” after the Latin “corona”, meaning “crown”. We now know these protrusions are spike proteins, which are the target of many vaccines currently being rolled out to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic.6

However, at the time coronaviruses were not thought to pose much of a threat to humans. Therefore, Almeida moved on and began studying other viruses that were known to cause serious illness.

In 1967, Almeida captured images of the rubella virus, revealing the molecular structure for the first time. The virus, which can cause miscarriage and birth defects when contracted by pregnant women, gave rise to a rubella pandemic in Europe and the USA from 1962 to 1965.7

Almeida’s images paved the way for a greater understanding of how rubella interacts with the immune system, leading to the first licenced rubella vaccine in 1969. In 2015, the World Health Organisation region of The Americas became the first region to eliminate transmission of rubella8.

Almeida then worked at Hammersmith Postgraduate Medical School where she made an important breakthrough in the understanding of Hepatitis B. Hepatitis B causes potentially life-threatening infections of the liver.9

Although first described in 1885, Hepatitis B was still baffling scientists in the 1960s. By capturing the first electron microscope images of Hepatitis B, Almeida discovered that it had two distinct antigens, one on the surface and one internally10. Again, her images proved important in understanding how the virus interacts with the immune system as well as identifying a target for the vaccine which is in use today.

In 1984, Almeida retired alongside her second husband, virologist Philip Gardner. She spent her retirement running a small antique business and training as a yoga teacher but was still on hand to advise with viral imaging. In the 1980s, she returned to St. Thomas, helping to capture the first images of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

June Almeida died at home in 2007, leaving a legacy of virology photographs and knowledge that still feature in textbooks today. From her beginnings as a teenage lab technician at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary to being awarded a Doctorate of Science in 1970, Almeida left a lasting mark on the field of virology. She solidified IEM as a rapid method for identifying and classifying unknown and newly emerging viruses. Her work was instrumental in moving forward our understanding of viruses: their morphology, their interactions with immune cells, and how to successfully target them with vaccines. More than 50 years on from her coronavirus discovery, we are reminded of the importance of her work which will no doubt continue to prove relevant in future virus outbreaks. Let’s add June Almeida to the list of pioneering scientists whose work is given the recognition it deserves!

The author recommends reading Lara Marks’ detailed biography and listening to Season 2 Episode 4 of the Surprisingly Brilliant podcast for more information about the life and work of June Almeida. For those interested in learning more about this incredible female scientist, here is a short succinct biography that was written by June Almeida’s daughter.11

This article was specialist edited by Ricardo Sanchez and copy-edited by Rebecca Budget

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/types.html

- https://www.whatisbiotechnology.org/index.php/people/summary/Almeida

- https://www.whatisbiotechnology.org/index.php/people/summary/Almeida

- https://www.scienceabc.com/innovation/what-is-an-electron-microscope-how-does-it-work.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1922067/?page=10

- https://www.immunology.org/public-information/guide-vaccinations-for-covid-19

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rubella

- https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=10798:2015-americas-free-of-rubella&Itemid=1926&lang=en

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2440895/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2440895/