Personal, protective but doesn’t-fit-ment

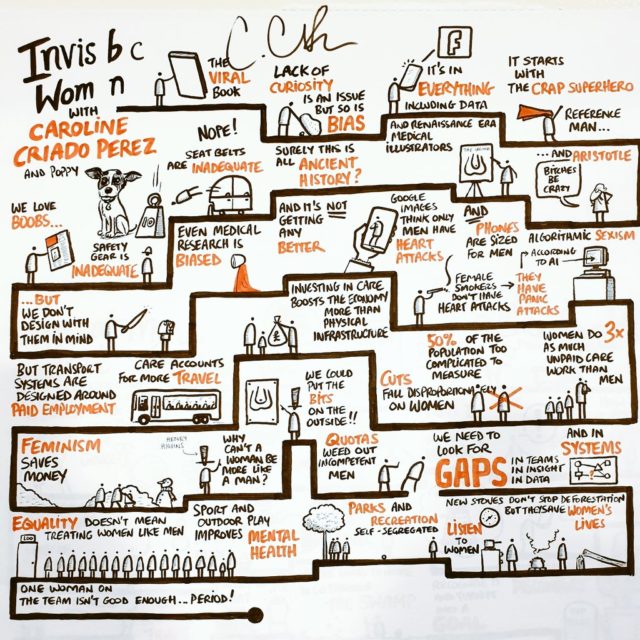

Some of the most exhausting social interactions involve making a complaint and then being told you’re overreacting. The brilliance of activist and writer Caroline Criado Perez’s book Invisible Women is that it gives you the evidence and vocabulary to articulate womens issues as facts, and not simply anecdotal complaints. The book elucidates the ways in which male-default thinking and male-based design can affect the experiences of women with regards to healthcare, transport, working hours (paid and unpaid), workplace, and health and safety regulations. Even though I turned into a preachy feminist to anyone who would listen, and was tempted to punch the book for being so infuriatingly on point at times, it is still required reading for anyone who wants to understand modern feminism. It isn’t just a memoir or a series of anecdotes but primary literature depicting how the gender data gap affects women.

If your day job consists of lab work, fieldwork, engineering, or if you studied science at any point, then you might be aware of personal protective equipment (PPE). This protection is a privilege stemming from the previous generation’s fight for safety in the workplace to both avoid large-scale disasters and more minor health issues — it is undoubtedly important. Unfortunately, women frequently reject these health and safety measures. PPE simply isn’t designed for a women’s size or fit: it’s uncomfortable, makes you clumsy in your work and keeps falling off or down. Gloves that are too large can make you accident-prone (like spilling toxic compounds or wasting precious product which you might have spent a working week making); gas masks that are too big don’t provide gas-tight protection; sleeves that are too long get pushed upwards, exposing the skin to dangerous materials; and eye protection can fall off your face when you look down. This danger of women rejecting PPE is compounded by the fact that chemical exposure affects women at a higher rate than men due to smaller lung sizes and thinner skin (meaning the chemicals can seep through the skin faster in women than men – possibly requiring even thicker gloves than provided).

So, why is this rejection unnoticed in the design and testing stages? Enter stage left: the gender data gap. Workplaces, tools, machinery, and PPE have been designed with only men in mind, either due to women’s initial exclusion from the workplace or the ignorance of physiological differences (such as women having smaller hands or being shorter). These oversights are at the expense of women’s ease — and more importantly, their safety.

My first exposure to this was when a male colleague jokingly came down to my height whilst working at a fume hood in the lab. He looked at the safety glass — which had an opaque bar that I couldn’t see past — and, suddenly serious, said, “Is that not really annoying?” Yeah, it was a pain, but I didn’t know any different. I didn’t know that, at his height, the opaque safety glass border didn’t obstruct his view; I didn’t know that he could see his hands, while safely behind the protective glass. From my (literal) point of view, the opaque edge of the safety glass obstructed my hands such that I would regularly not use it. Since “74 % of PPE was designed for men”, it’s fitting that the fume hood design didn’t consider this view obstruction. I genuinely wasn’t angry because I had no idea anyone had a different and easier time of it. It’s this exact thinking that resulted in European, able-bodied and male-focused equipment with the group-thought: my experience is the universal experience. This is not an anomaly – “57 % of women said that their PPE ‘sometimes or significantly hampered their work’” so is it a wonder that they reject it?

Lack of female consideration in design isn’t limited to PPE and can include architectural misgivings. I’m a small person and had a stepping stool named after me in a café I worked at. I’ve never taken offence (there are more things the world teaches you to be insecure about than your height) and honestly, I always thought it was sweet. But it turns out that having things out of reach might be more systematic than I thought. In fact, the female body was rejected by architects when devising a standard human model to design spaces around; it is instead represented by a six-foot man with his arm raised, even though women are, in general, around 10cm shorter1. Other relics of a male-dominated workspace that I’ve personally experienced include having to go down two flights of stairs (past two male toilets) to the female toilet at work; and you can only imagine the inappropriate posters on the wall of a male-dominated room in a previous workplace (reminiscent of a teenage boy’s bedroom).

Above are just the experiences of a white and able-bodied woman. Male-dominated workspaces can lead to social exclusion as well, with 100% of women of colour interviewed for a study into gender bias reporting that they had experienced this2. Reminiscent of men in a cigar room discussing business, money and policy while the ladies sit in another room missing out (or, for a pop-culture reference, when Rachel in Friends takes up smoking to be part of the major discussions at work).

There’s a certain joy I feel when the scientist in a text is referred to as she. According to Criado Perez, this might be because we don’t imagine a female scientist due to male-default thinking — where the reader assumes the gender of “they” based on the gender stereotypes of the job or action (i.e. male doctors and female nurses; he was assertive, and she was bossy). In a worrying development, these stereotypes are now being fortified with algorithms, such as Google Translate assuming gender where nouns require a masculine or feminine differentiator.

In academia, only initials are used when referring to authors. The reader can then, in theory, remove their unconscious gender bias about the authors, in reality, however, this is not the case. “One analysis found that female scholars are cited as if they are male (by colleagues who have assumed the P stands for Paul rather than Pauline) more than ten times more often than vice versa” leading to work authored by women being attributed to men (even if mistakenly). It was found that “female-authored papers were accepted more often or rated higher under double-blind review” implying the idea that publishers prefer papers from male authors. Additionally, women are systematically cited less often than men, which matters since citations are important for giving weight to research. Both publications and citations are key to career progression in academia. However, women fall short in both areas, keeping them on a slower career path compared to their male counterparts – possibly contributing to widening the gender pay gap. The most insidious example of sexism in STEM that Criado Perez makes is that “Male academics – particularly those in STEM – rated fake research claiming that academia had no gender bias higher than real research which showed it did”. This is just disheartening. If male academics – experts in objectively obtaining facts by their job description — believe so, then it’s unsurprising that girls as young as 6 are less likely to think of women as “really, really smart”, and more likely to avoid activities for “really, really smart” children. Female design can be amazing and innovative. Projects like the pioneering urban planning in Barcelona are being led by women and it’s game changing3, including redesigning public toilets and childrens’ play area layouts to make both more inclusive; the physical representation of the hyperbolic plane was unknown for a century before mathematician Daina Taimina simply crocheted it into existence4 (think of a holly leaf, all curled out on itself); and Transport for London recently brought out a range of PPE for women. We need to support this inclusion and direction, to make sure the next generation of 6 year olds know that women can be “really, really smart”; because so many women are and they need to believe it.

If you would like to read more about this topic you can find some further reading here: https://tinyurl.com/sh8dtpm

This article was specialist edited by Kirstin Leslie and copy-edited by Dzachary Zainudden.

References

- https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/average-height-by-year-of-birth?tab=map)

- https://mashable.com/2015/01/26/women-of-color-stem-research/?europe=true&utm_cid=mash-com-Tw-main-link

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-50269778/what-would-a-city-designed-by-women-be-like

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w1TBZhd-sN0

1 Response

[…] Now that Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is in the public eye due to COVID-19, here’s part of an article that was previously published for The GIST. […]