Abolishing anonymity: the implications of genetic sequencing technology

The world is a divisive place; there’s no doubt about that. But if there’s one thing that unites us through politics, social class, economic status, and geography, it’s our DNA: the 23 tightly coiled chromosomes sat neatly in the nucleus of almost every cell. We are 99.9% similar to every other human being on the earth and that unique 0.1% is what makes us who we are1.

Over the past 10 years, there has been a monumental rise in technologies offering gene sequencing, DNA decoding, and ancestry answers. DNA sequencing went from an insurmountable task costing billions of dollars to one as easy as spitting in a tube and waiting two weeks.

If you’ve ever thought about taking advantage of these new gene sequencing technologies, then you may have considered industry leader and Google funded 23andMe2. Cooked up in California’s Silicon Valley, 23andMe encourages users to ‘Commit to a healthier you, inspired by your genes’. It offers a £79 ancestry package, designed to help you ‘Experience your ancestry in a new way!’, or for £149, you can ‘Get an even more comprehensive understanding of your genetics’ and delve into disease-causing gene variants. 23andMe has an estimated 6 million users, and lead competitor Ancestry.com claims it has tested around 10 million people.

23andMe can give you reports on ‘wellness, health pre-dispositions, disease carrier status’ and, rather nebulously, ‘traits’. Traits include relatively amusing propensities like ‘eye colour’ and ‘unibrow’ (look in the mirror?), ‘aversion to coriander’ (you probably knew you didn’t like it already), ‘ability to detect musical pitch’ (ask your primary school choir-master) and ‘earwax type’ (no, I don’t know either). Inconsequential traits aside, it also uses your data-rich DNA to identify family origins and identify any disease causing variants.

DNA sequencing works by shearing our DNA into bite-sized chunks and detecting the specific order of bases: A, T, G or C. Bases are the building blocks of our DNA, and the order of our bases determines how the gene functions. The order of bases in a gene sequence are aligned and compared to a reference sequence, a pre-existing genome. A genome is the complete set of genes in an organism. This sequencing can then show any variation within a gene, such as base rearrangements, base deletions, or insertions of new bases3. 23andMe only sequences the specific genes which code for the traits they’re looking for, instead of sequencing the entire genome, keeping costs down. Identifying changes in base sequences can reveal if someone has a higher chance of developing a disease. It can also identify your close family members because gene variants are inherited. By comparing a selection of genes from different family members, a family tree can be established.

This technology affords us a great scientific advantage over our genetic futures in terms of detecting and treating diseases, but it’s a double-edged sword. Multiple people have been sued by sperm cryobanks for using tests to find the sperm donors that were used to conceive their child. Doing so is a breach of many sperm bank’s anonymity clauses. Danielle Teuscher sequenced her donor-conceived daughter’s genome using 23andMe, and discovered a relative of the sperm donor. Upon making contact with the sperm donor’s relative, she began to receive cease and desist letters from Northwestern Cryobank, threatening to seek $20,000 in damages. They also revoked her access to four additional donor sperm vials, preventing her from having children that would be genetic siblings to her daughter4.

A quick Google search shows many different cases of egg or sperm donor’s anonymity being breached by the data these tests are producing and the countless lawsuits that follow. These issues are raising questions about the long-term financial viability of sperm and egg donation centres. They thrived and profited off guaranteed anonymity for the donors, but due to widely available sequencing services, this is being compromised.

These events are becoming so frequent that a large charity called NPE Friends Fellowship has been created5 to support those who have discovered their presumed biological parent is actually of no relation. This is called a ‘non-parental event’, or NPE. In some cases, people are finding out their parents are adoptive, their mother is actually their aunt, or another disruption of presumed family lineage6. This understandably can be devastating to some, but revolutionary to others. Whole branches of family can be uncovered, and new, positive connections forged7.

This isn’t to say that sequencing the genomes of adopted, donor-conceived, or naturally conceived children is a bad idea. Sequencing can still offer more insights into disease causing gene variants than simply doing nothing for everyone. This could give parents an idea of what their child could encounter as they grow up, from propensity to develop Alzheimer’s, to if they’ll like coriander. Importantly though, the American Food and Drug Authority actually pulled 23andMe’s ability to offer disease variant sequencing, claiming ‘the company lacked the proper approval to give people potentially life-altering information about their health.’ Their ability to offer this service in the US has been reinstated, but this level of scrutiny was never applied in the UK.

Despite diagnoses potentially saving lives, famed geneticist and author Adam Rutherford described the genetic tests supplied as nothing more than ‘trinkets’ in an interview with BBC Radio 4’s ‘Beyond Today’ podcast on the 6th of June, 20198, echoing the FDA’s previous comments. He says that these tests are extremely good at uncovering adoptive parents and finding new family members, but 23andMe’s testing kits should not be used in conjunction with diagnostic techniques within the NHS. 23andMe is a private company and are therefore “less bound by the scrutiny of public services and academic resources. We do have projects like this already…The NHS is the world leader in genetic sequencing services, and allows for an extremely valuable insight into the future of genetic technology.” He adds “The more openness and public scrutiny there is, the better.” He adds that GPs and doctors should be trained in decoding these results to ensure the highest level of genetic care can be met9.

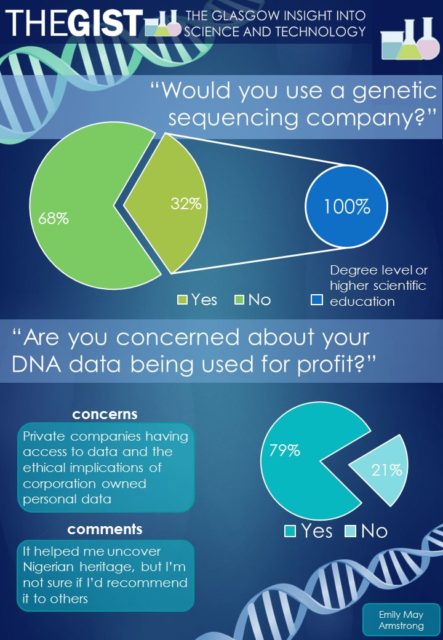

A 24-hour Instagram poll with 63 participants (aged 20-45) uncovered how some of the public view genetic sequencing technologies. This was run by the author, on their Instagram account (@emayarmstrong, story highlight “sequencing”). Participants were from the UK, India, America, Australia, and South Africa. From this, only 32% said they would be comfortable ‘using a genetic sequencing company like 23andMe’, whereas 68% said they would not. Secondarily, 79% of responders were concerned about ‘data safety and genetic data being used for profit’. Interestingly, 20% of responders said they would still use a genetic sequencing company even if they’re concerned about anonymity and data privacy. People were concerned about ‘Private companies having access to data’, ‘the ethical implications of corporation owned personal data’, ‘risks of police and FBI accessing data’, and also said they ‘distrust the accuracy of such tests’. Equally, people were keen to underline the potential ancestral benefits of sequencing. One person found they have ‘very strong Nigerian ancestry’, but added they ‘may regret using the service in the future.’ Perhaps of most interest, people with degree-level education in a science subject were the most against sequencing their DNA.

The public’s distrust of 23andMe’s genetic data collection has some weight behind it. In 2018, 23andMe partnered with pharmaceuticals giant, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), beginning a ‘Multi-year collaboration expected to identify novel drug targets, tackle new subsets of disease and enable rapid progression of clinical programs’10. This partnership is fuelled by a $300 million investment in 23andMe from GSK. On the surface, this sounds like an excellent opportunity to create novel and tailored drugs for a variety of genetic diseases. But 23andMe users were never consulted if they could have their data passed on to third parties, nor were they allowed to opt-out of this at point of purchase. This is wrapped up in legal jargon in the terms and conditions we all blithely click through, which is legal to do. Essentially, this has flipped the customer into becoming a product. The customer pays to receive their sequencing data; the sequencing company sells their data on, creating tailored medicines. These medicines are then marketed back to the consumer who originally provided their data.

This isn’t to say having easy-access to affordable sequencing technologies is necessarily a bad thing. In April 2018, the infamous Golden State Killer, Joseph James DeAngelo, was apprehended after 30 years because of DNA evidence. A third cousin of the brutal serial murderer and rapist uploaded their DNA to open-source ancestry service, GEDmatch11. GEDmatch lacks the data protection laws that larger companies like 23andMe have, meaning no search warrant was required by the Californian investigators, so they could match DNA from a previous crime with the relative’s genome. This was momentous for law enforcement, survivors of the Golden State Killer, and gene sequencing technologies. This also uncovered a relatively unnerving statistic: A third cousin making their genetic data publicly available makes 60% of the white American population identifiable12.

Curiously, while researching this article, I was targeted on both Instagram and Facebook by a company called ‘GenomeLink.io’ using ads. GenomeLink takes data produced by 23andMe, and runs further ‘analyses’ on the data provided. It promises to ‘curate thousands of research studies to bring you the newest insights from the frontier of genomics research.’ How it does this is entirely unknown. GenomeLink claims it can analyse ‘morningness’, ‘neuroticism’, ‘loneliness’, ‘breast size’, and ‘waist size’. I was unable to find any scientific literature to confirm these traits could be quantified using gene sequencing. Given that 23andMe only sequences specific genes that are known causes of specific traits, it would be impossible for any inferences about new traits to be made by this company. The data simply isn’t there. Furthermore, it is a shell company of a larger company called ‘awaken.co’, whose website claims it’s creating ‘an infrastructure for consumer genomics’. The ‘trusted review partners’ are all investors of the company, and the board involves people with little-to-no obvious scientific training. The aggressive marketing tactics used by this company underlines how much profit can be made through these additional services. It also demonstrates how unwitting users of 23andMe could easily be duped into handing their data over to yet another data-mining company. The company has disabled Instagram comments under their ads, probably due to a slew of disgruntled customers, reflecting the disappointment shown by customers on Facebook.

The upshot of considering all these points? Genetic sequencing is an incredibly powerful technology but needs to be used sensibly in accordance with proper data protection laws. If you submit your DNA for sequencing, you should be aware of the support networks in place if you find something life-changing – whether that’s a new family or a new genetic disease. Also, make sure you read through those terms and conditions and opt-out of anything that makes you remotely uncomfortable. Genomic datasets are the richest available, and we need to use them wisely. As a geneticist with their own genetic disease, I highly doubt I’ll be signing up to spit in a tube any time soon.

This article was specialist edited by Rachael Burrows and copy-edited by Sonya Frazier.

References

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2002/12/021220080005.htm

- https://www.23andme.com

- https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Sequencing-Human-Genome-cost

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/woman-finds-sperm-donor-after-using-dna-test-raising-questions-about-donor-anonymity

- https://www.npefellowship.org/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/28/science/dna-tests-ancestry.html?module=inline

- You can read more about uncovering new family ties here https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/sep/18/your-fathers-not-your-father-when-dna-tests-reveal-more-than-you-bargained-for

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p07cfghs

- You can find an article written by Adam for The Guardian about 23andMe here https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/aug/10/dna-ancestry-tests-cheap-data-price-companies-23andme

- https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/gsk-and-23andme-sign-agreement-to-leverage-genetic-insights-for-the-development-of-novel-medicines/

- https://www.gedmatch.com/login1.php

- https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/10/we-will-find-you-dna-search-used-nab-golden-state-killer-can-home-about-60-white