The dairy life: building immunity through breast milk

The immune system has been constantly adapting since the day we were born. Whenever we come down with a fever, immune cells are actively targeting and eliminating foreign agents that cause disease while returning the body to a healthy state. Throughout our lives, this system is also exposed to a wide variety of pathogens, therefore it must be able to provide protection against most diseases. Some bacteria are not eliminated by the immune system and may be beneficial to us without posing a threat. They can also integrate into our microbiome – a community of micro-organisms which thrive within us and outside of us. However, if our immunity and microbiome continuously develop alongside us, it is interesting to consider how both of them came to be in the first place.

Directly after birth, our immunity and microbiome can develop through the act of breastfeeding. This is a method wherein young babies acquire immunity through antibodies in breast milk, which are passed from mother to child. These antibodies, termed ‘maternal antibodies’, play an important role in the prevention of infection. Our bodies will produce numerous types of antibodies on their own as our body grows and develops further, but breastfeeding helps children get a head start by ensuring that they are protected from common infections that their mother has previously been exposed to.

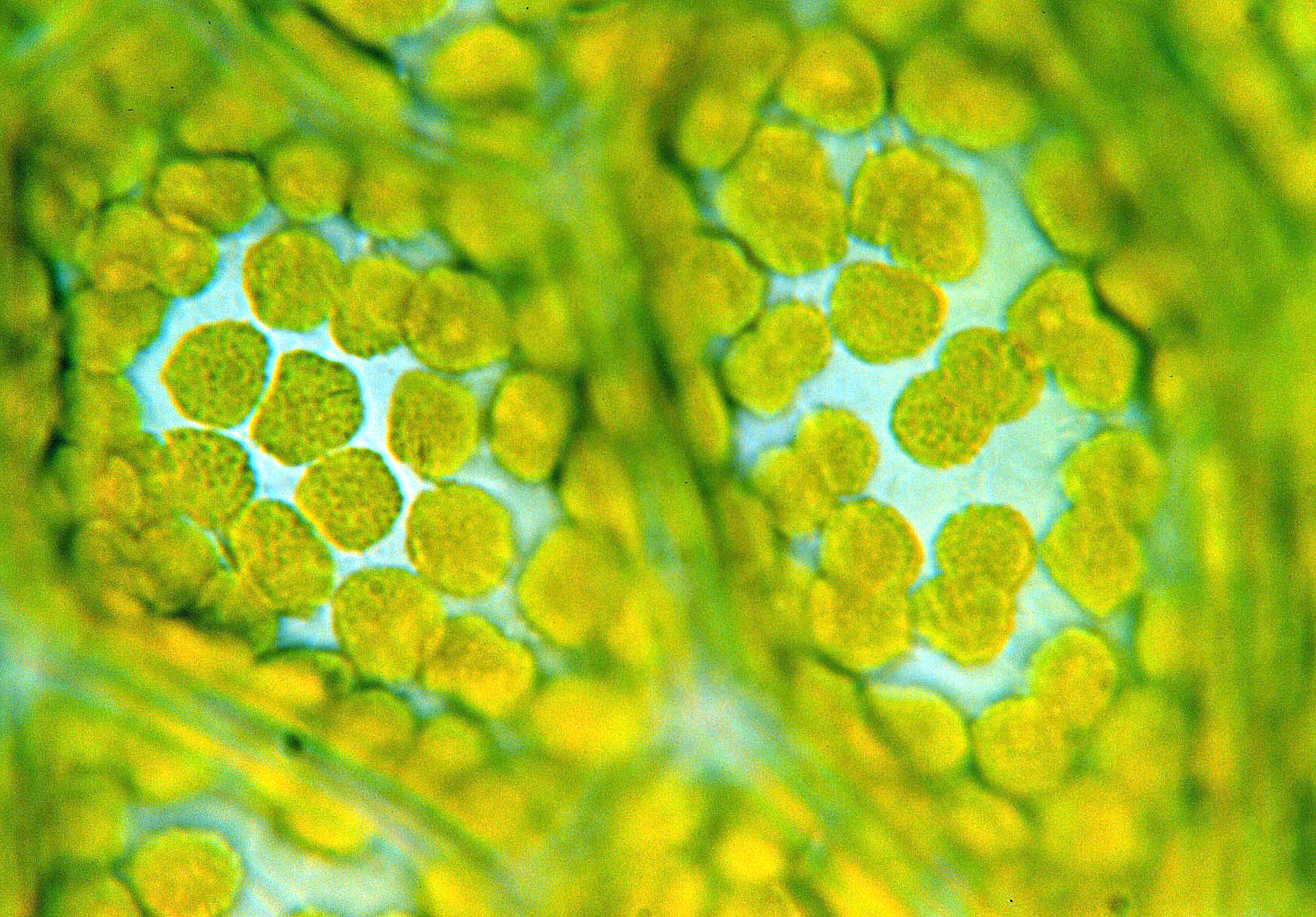

There are five classes of antibodies within our body that differ in size and function. Those that we receive through breast milk are members of the IgA classification. This particular antibody specialises in neutralising harmful pathogens and trapping them so they cannot infect host cells. Other immunological components that babies receive from their mother vary between individuals and can be influenced by a number of factors, including how early she begins lactating and her health and diet. Vânia Vieira Borba from the Coimbra University Hospital Centre claimed that colostrum (the first milk a mother produces) contains numerous antibodies, inflammatory mediators, and other molecules which efficiently build a foundation for the baby’s immunity1.

It is important to bear in mind that the aforementioned foundation of immunity protects the child temporarily. Despite the antibodies and immunological components provided through colostrum, the immunological composition of breast milk decreases over time and makes it more nutritionally beneficial for the child instead. Therefore, once the child has been exposed to their environment, it becomes necessary for them to develop their immunity naturally. It is also essential for the child’s immune system to begin producing its own antibodies rather than acquiring temporary protection from their mother’s antibodies.

Fortunately, natural immunity through environmental exposure can begin during the act of breastfeeding itself. As the baby suckles, microbes can transfer from their mother through skin-to-skin contact, helping to establish the infant’s personal microbiome. Furthermore, bacteria such as bifidobacteria can accumulate in the gut soon after birth following the ingestion of milk. Once the baby begins to wean and they are introduced to solid foods and other sources of nutrition, they will have built a microbiome that is inhabited by a variety of bacterial species which are beneficial for their well-being and health.

One thing to consider is the comparison in immunity and microbiome development between babies being fed with breast milk and those fed with formula products. The latter is an important option for mothers who are unable to breastfeed or personally choose not to, so research and development is dedicated to

What is also surprising is the fact that breastfeeding may be associated with protection against autoimmune diseases. For example, an investigation in the United States was conducted to detect any association with gut microbiota and the development of asthma in children4. Christine Johnson and Dennis Ownby, who conducted the research, suggested that abnormal microbial composition within the gut can influence how pediatric asthma can develop and ingesting breast milk could preserve a healthier gut environment. However, further studies would be recommended in order to determine the plausibility of this theory before determining if breastfeeding increases a child’s tolerance against asthma and other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis5.

Nevertheless, it is remarkable to see that when a baby is born, they are not only receiving a nutritious start in life from their mother’s milk but also the building blocks of their immunity. The idea that milk could potentially aid in decreasing the prevalence of autoimmune diseases is also intriguing, but more evidence is necessary to prove this. So until then, it should be said that when it comes to fighting infections and getting back on our feet, mother really does know best.

This article was specialist edited by Niamh Armstrong and copy-edited by Caitlin Duncan.