Book Review: “SUPERIOR”, Angela Saini’s riveting takedown of the return of race science.

Angela Saini is my one of my favourite authors. I plunged into the descriptive and critically aware world of Inferior, Saini’s second book, over Christmas 2017, refusing to leave the house so I could finish it. I loved it; however, I was torn between the carefully crafted statistics, insightful history lessons, and the fact we needed this book at all. We shouldn’t need to have the historical misdeeds of the entire scientific community read to us, because in an ideal world, they wouldn’t have happened.

But, obviously, we don’t live in an ideal world (sorry to break it to you, everyone). And Angela Saini’s latest offering couldn’t have come at a more poignant time for us socially, economically, or politically. Her signature writing style, weaving descriptive narrative with cold-hard-facts, has morphed into compelling, almost edible prose. This should be required reading for absolutely everyone.

In ‘Superior: the return of race science’, Saini begins with her exploring the British Museum, considering the fall of previous empires. She examines how tourists long to understand their place in the world; unfortunately, doing so under ‘cold, neoclassical pillars’ instead of their home countries, where these artefacts belong. This aptly sets the tone for the deep-exploration of history, culture, and scientific racism which unfolds throughout the book.

Meeting countless historians, biologists, and experts, Saini underlines that scientifically, we may all be the same species, but it is human power structures driving wedges between us. In the first chapter, ‘Deep Time’, Saini travels to Australia. The colonialist legacy left by Europeans is still felt to this day and bred an inherent mistrust of the ‘savage other’. And science hasn’t done anything to change this. Scientific papers on ‘racial hygiene’ drove the holocaust1, while eugenics programs led to the forced sterilisation of hundreds of women of colour2. Even now, there are scientists who continue to undermine efforts to rebalance racial inequality. If you thought all science was objective, you’re wrong.

Scientific research mimics subjective views held by scientists. If we have biased scientists, we’ll inevitably end up with biased science. And this has been true for centuries – ‘modern’ science rose from Euro-centric colonialism and imperialism3, and has projected its racist ideals far and wide. Saini interviews Jonathon Marks, Professor of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina, who says that race science itself emerged ‘in the context of colonial political ideologies, of oppression and exploitation’. This was further reinforced in slavery, where ‘black diseases’ were invented to account for slaves trying to free themselves from their torturous lives in the US.

Saini deftly navigates between the origin of eugenics (believing gene variants make one inherently better than another) to a curious and shocking academic journal, Mankind Quarterly. Mankind Quarterly is still publishing fringe race science in 2019, funded by dwindling, but nevertheless nefarious sources. It received praise from US president Ronald Reagan, and publishes ‘evidence’ of ‘scientific’ discrepancies in IQ between races, amongst other shocking un-truths. This exemplifies that anything using biased scientific methods can describe itself as ‘scientific’, therefore reinforcing falsehoods about race. Race science never really went away. Instead it sits festering, driven by blinkered academics, including Mankind Quarterly’s Assistant Editor, Richard Lynn of Bristol University (Ulster University recently withdrew his emeritus professor status following a complaint that he advocates sexist and racist views).

In Chapter 6 – ‘Human Biodiversity’, the rise of easily accessible sequencing technologies is covered, considering how the now age-old race difference argument is being rinsed-and-repeated in a new, technological age. The Human Genome Diversity Project4 in 1991 set out to sequence small ‘splinter groups’ of society: Kurds, Native Americans, and the Basques. Unfortunately, Saini points out this is simply replacing ‘race’ with ‘population’, and ‘racial differences’ by ‘human variation’. It seems that even in this ‘objective’ and technologically-driven age, scientists aren’t immune to internalised racist beliefs.

Moving on,‘Caste’, the third-to-last chapter, shakes us back down to the harsh reality of India’s modern-day social stratification system; further reinforcing that race-lead discrimination still runs rampant in even the most technologically advanced countries5. It may go without saying that British colonists reinforced this system. We got to move on, India didn’t6. Children from ‘lower caste’ backgrounds have been forced to clean toilets at school, and the majority of students in the top universities are still from ‘upper castes’7. She deftly points out that differences in nutrition, education, healthcare, and stress levels directly impact a person’s ability to perform to specific tests. If you haven’t had access to a variety of positive indicators such as social class, nutrition, education, you’re not going to do as well. The better access you have to these things, the better you do in life. This has nothing to do with a person’s race, it has everything to do with systemic societal oppression.

In short, this book is timely. Recent upswings in racist, populist, and authoritarian politics has fuelled an increase in ideological white supremacists, who frequently rely on ‘race science’ to add weight to their otherwise vapid arguments. As a white geneticist from the UK, this book forced me countless times to sit with the uncomfortable history of my ancestors, and to acknowledge how my chosen subject has forced people across the world into suffering. This book is in equal parts arresting historical storytelling, and an urgent call to action. Saini urges Superior’s readers to systematically assess their racial privilege, and vigorously critique what science presents as objective truth.

Unfortunately, at the time of writing, rampant racism from the far-right on Twitter has lead Saini to make her account private. She reports, “In the last few days I’ve seen a concerted, deliberate attempt by a network of alt-righters to discredit my work. In the process, they laid their racism so bare that it utterly backfired”. If that’s not evidence that this book is timely, important, and true, then I don’t know what is.

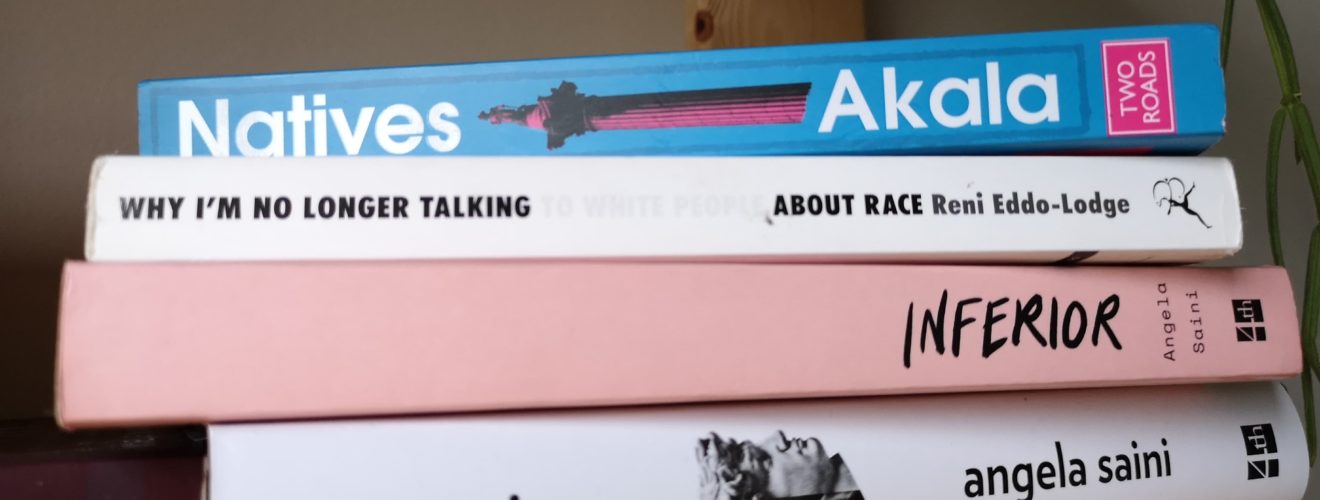

If you would like to read any of Angela Saini’s work, she’s published by Fourth Estate. If you want to learn about the history of racism and imperialism, check out ‘Natives’ by award-winning orator, rapper, and novelist, Akala. Finally, if you want to understand the history of racism in the UK, read ‘Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race’, by award-winning writer, Reni Eddo-Lodge.

This article was edited by Katrina Wesencraft.

References

- https://www.fasebj.org/doi/abs/10.1096/fj.08-0202ufm

- http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/unwanted-sterilization-and-eugenics-programs-in-the-united-states/

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/topics/reference/colonialism/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/nrg1596

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-35650616

- http://www.historydiscussion.net/history-of-india/eighteenth-century/life-during-eighteenth-century-in-india-indian-history/6347

- https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043303?journalCode=soc