The Impact of a Name: Our Passive Response to Climate Change

“A rose by any other name would smell as sweet”, Romeo so eagerly suggested of his ill-fated lover in the Shakespearean classic. But was Romeo wrong? What if the name we label something with defines it in the public eye? Take your own name for example – the first thing most people learn about you is your name and at that stage they start to build a mental profile about you. Perhaps they know someone that has the same name and they start to link traits between you, without actually knowing you at all.

And what if this phenomenon extends to our politics? Climate change has been used interchangeably with global warming to describe the evolving period of warming that the Earth has been going through for as long as I can remember. Yet, in 2009 a study investigating the public understanding of “climate change” in comparison to “global warming” 1 found that only 1% of people surveyed were unaware of the terms and their implications. Interestingly, referring to the problem as global warming “evoked more concern” than climate change. So people do react to each name differently.

At the time that paper was published, 63% of Britains saw global warming as less serious than other issues, and you will not be surprised to read that the opinions of political and business elites presented on news outlets have a significant impact on the general public’s perception of issues 2. Does referring to the challenges our environment faces as “climate change” really engage you in the seriousness and the shared responsibility we should all feel? Would our opinions and feelings of the problem be different if we called it something closer to what the real cause of the problem is, rather than the outcome? For example, take the 1960s tragedy which occured when a drug used to reduce morning sickness during pregnancy led to limb deformities in infants. This event is not named for the resultant phocomelia, but for its cause, Thalidomide. It follows that our environmental issues should be referred to in the same way, and I would propose “The Human Pollution Pandemic”.

Over the past 30 years there has been little doubt about the downward trend of the biosphere: global temperatures are increasing; sea levels are rising with an increase in surface sea temperature; the frequency of natural disasters is expected to increase, as is the magnitude of the events; bleaching of coral reefs is becoming ever more widespread; and more species than ever before are predicted to be “committed to extinction” by 2050, reducing biodiversity and disrespecting the integrity of our world. While there is an understanding that we are responsible for these issues for the most part, we still allow ourselves to be passive in our response to it, even while understanding how damaging it will be in the future. It’s doublethink, and we prefer it that way.

This sort of doublethink has become prevalent in our modern society. In 2016, Oxford Dictionaries designated “post-truth” as its word of the year, defined as “circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”. Steve Tesich, the famous Serbian-American playwright, first used the phrase in an essay in 1992 relating to the disdainful way in which Americans had reacted to the uncomfortable truths that appeared following the Watergate scandal. He wrote “In a very fundamental way, we, as a free people, have freely decided that we want to live in some post-truth world” 3. While the Watergate scandal has mostly been left to history (although with the Trump Administration, maybe we can expect Watergate II any day now?), our ability to shy away from uncomfortable truths, such as the mortality of the Earth and our responsibility for its accelerated demise, continues to shock and amaze. The problem we face is that climate change has already gone too far and we cannot allow ourselves to ignore the facts any longer; the seriousness of it demands that we make it a priority.

A recent study has looked in detail at the driving forces behind changes in the Earth’s climate over the past 4.5 billion years. Since the 1950s, global temperatures are estimated to have increased at a rate equivalent to 1.7 Celsius per century. In the 4.5 billion years prior to the ‘50s it fluctuated by 0.01 degrees per century, meaning humanity’s impact on climate change is 170 times greater than traditional natural drivers, such as volcanic eruptions, Milankovitch cycles (the changes in the Earth’s physical movement in space), albedo (the amount of heat reflected by the Earth), and sea temperatures 4. We don’t just rival Mother Gaia, we have dominated her. This research underlies calls to declare the end of the Holocene period of Earth as being prior to 1950, with the current period being labelled the Anthropocene to reflect the significant human impact in accelerating the changing the state of the planet.

Our pollution is everywhere: chemical pollution is widespread in seawater and freshwater; greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have surged to new concentrations and are now 145% higher than they were pre-industrial revolution 5; the rubbish we dump pollutes ecosystems everywhere in the world.

Photo of East Beach, Henderson Island. Credit: Tara Proud.

But if we think that it’s only the environment that is affected, we are very wrong. The impact on global health of humans is extremely significant too.

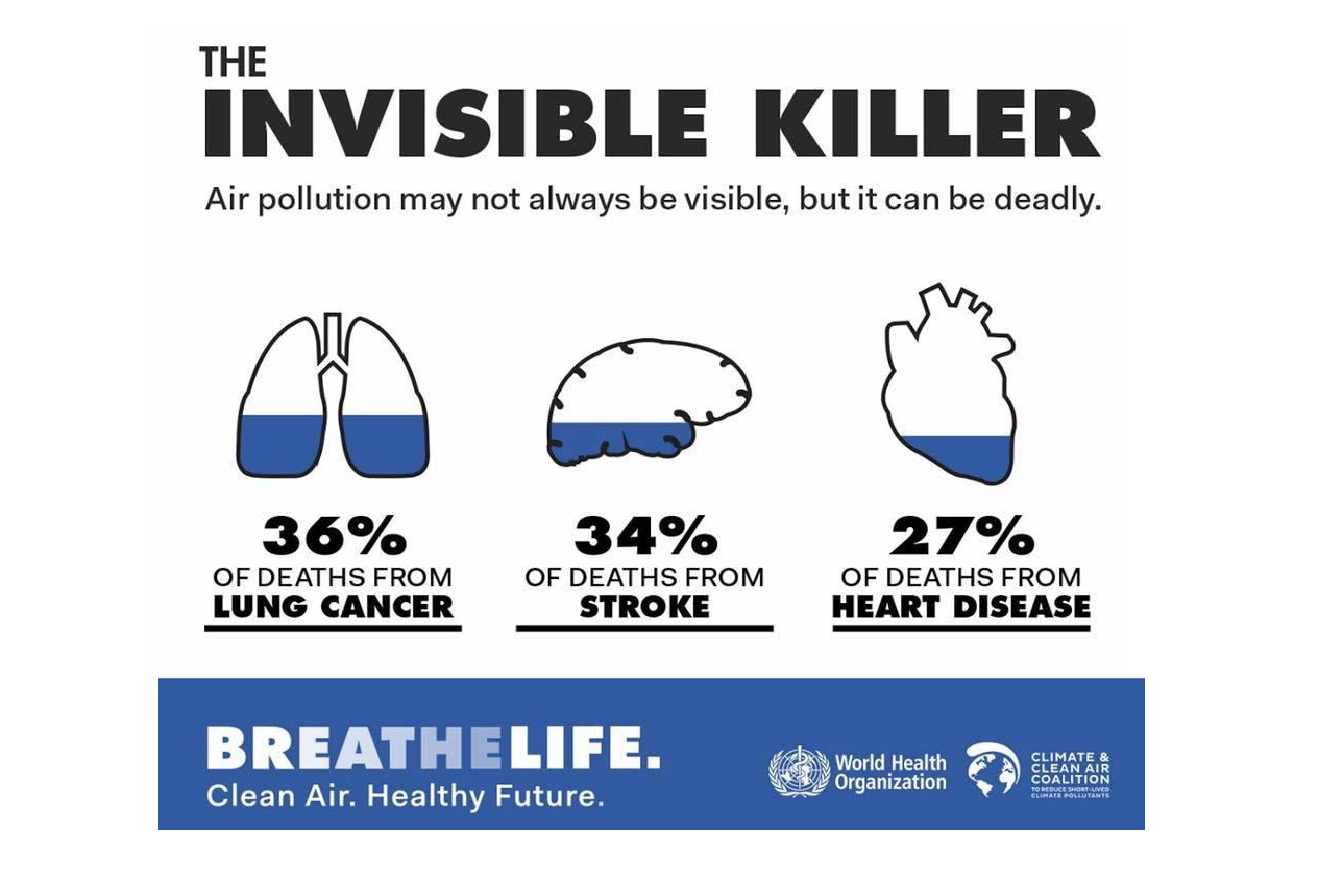

Between 2010 and 2016 the World Health Organization (WHO) compiled a worldwide study into the amount of air pollution across the Earth. They concluded that every year more than 7 million people die as a result of poor air quality (air with significant particulate matter found within it) 6 This figure is expected to double by 2050 7. On top of the study by the WHO, The Lancet Commission calculated that at least 9 million people die annually as a direct result of exposure to polluted water, soil, and air 8. This accounts for at least 1 in every 8 deaths globally as a direct result of pollution; significantly more than AIDS (approx. 1,500,000) and malaria (approx. 500,000). Can we really refer to this level of mortality as “climate change”? I think we are a long way beyond that. Let’s take a look and compare to the most significant pandemics the world has experienced:

- The Spanish Flu – estimated over 21 million dead 9

- The Black Death – 50 million deaths (14th century) 10

- The Plague of Justinian – 25–50 million dead 11

- The Antonine Plague – approximately 5 million deaths 12

- The Plague of Athens – 75,000-100,000 people died 13

With human pollution causing the deaths of over 9 million people every year (with some estimates as high as 62 million), this could already be classed as one of the largest pandemics in human history, and it shows no signs of slowing. This doesn’t even factor in the impact we have on biodiversity within the world as a whole, which is also likely to negatively affect human life.

Image Credit: World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/en/)

While global climates have been proven to change naturally, and have done so predictably throughout history, it is no longer an option to ignore the scientific proof we play a role in this. In the truest sense, what we are experiencing is some kind of pandemic. It is not just affecting the population of humans of the world, it is more like the most dangerously mutated virus you can imagine, affecting all organisms and ecosystems on the planet. The only species capable of finding a cure, is ourselves. In 1971, when Edgar D. Mitchell was returning from the lunar mission Apollo 14, he saw the whole Earth out his window and realised that to “solve the eco-crisis… a transformation of consciousness” was needed. Almost 50 years later we are still waiting for this transformation to happen politically and, while the world is in turmoil, millions more people will die. It appears that though we may be able to quietly distance ourselves from the environmental risks posed by global warming, perhaps considering risks to the health of the global population will evoke a more urgent response to the problem. Remember the response to the anticipated bird flu epidemic? The reaction to the threat to human life was incredible. Tamiflu was mass-produced and stockpiled immediately, at the cost of millions of pounds and, in the end, we never even needed it 14. That is the response we need to the pollution pandemic.

Paul Valéry, a French poet with a passion for scientific speculation, wrote in 1937 that “the trouble with our times is that the future is not what it used to be”. The future we were promised wasn’t meant to be a battle to regain control of our environment, it was meant to offer hope and opportunity to reach the furthest possibilities of human ingenuity. Think of the futures imagined in movies like Back to the Future: hoverboards, flying cars. Instead we have the beginnings of Mad Max. The world has become stuck in an infinite loop of existing behind the lies we choose to digest from the mouths of those we want to believe know better than us. But, by accepting the scientific truth in front of us we will accept that ‘The Human Pollution Pandemic’ is here, and we can objectively look at where we have come from, and make the changes necessary to positively impact the world we live in.

Humanity has solved countless seemingly impossible problems in history and now we face our greatest challenge yet. Can we accept our blame and work together globally to make our world a better, healthier place? Or do we follow the status quo and trust in policy makers to fix it for us? The only “transformation of consciousness” likely to take place if we select the second option is that it will become every nation for itself and our global situation will only get more desperate and extreme.

This article was specialist edited by Jonathan Bowes and copy edited by Kirstin Leslie.

References

- https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662506073088

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10584609.2017.1380092

- Tesich, 1992, “A Government of Lies”, The Nation. 6, Jan 1992, 12-14

- http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2053019616688022

- https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/greenhouse-gas-concentrations-surge-new-record

- http://www.who.int/airpollution/data/cities/en/

- doi: 10.1038/nature15371

- https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/pollution-and-health

- http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dm18fl.html

- Ole J. Benedictow, “The Black Death: The Greatest Catastrophe Ever”, History Today Volume 55 Issue 3 March 2005

- Rosen, William (2007), Justinian’s Flea: Plague, Empire, and the Birth of Europe. Viking Adult; pg 3; ISBN 978-0-670-03855-8.

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4381924.stm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19787658

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-26954482