Brexit Brain Drain

The results of the EU referendum have come as a shock to many within the scientific community around Europe; after final polls released in the early hours of Friday morning predicted a significant lead by the Remain campaign, the news that the UK would be in fact leaving the European Union has been met largely with alarm and dread. Prominent figures within the community have long been voicing concerns that a vote in favour of Brexit could be a big problem for some of the foundations of scientific research. Funding, collaboration and attracting new talent form the core of most research institutions, and have allowed paramount discoveries and developments to be made.

So what makes researchers so worried now that the official result is to leave? With the support of Remain campaigners, multiple financial experts warned about a recession that could be triggered if the UK voted to leave. Although circumstances are still uncertain, the record-breaking crash in the financial markets since Leave support emerged at the last minute suggests that there may be less money available within the government to spend on areas such as research and development. The EU currently provides billions in research funding to the UK, with some estimates showing a net contribution of €3.4bn from the EU towards research and development between 2007 and 2013 1. An additional analysis between 2014 and 2015 found that “EU funding supported 8,864 direct jobs, £836m in economic output and a contribution of nearly £577m to GDP” 2. As part of this, the EU provides access to large funding pools such as Horizon 2020 that promote collaborative work, and there are several fields that are almost entirely dependent on funding from the EU to function.

As access to EU funding is removed, many researchers are deeply concerned that they may find themselves out of pocket if these funds are not replaced in any way by the government. Projects may find it much harder to find the resources to get off the ground, putting UK science at a major disadvantage compared to those within the EU or the USA, and unfortunately the disparity between current funding levels and those provided solely by the UK government may be too vast to replace. A report investigating EU funding for UK research, spanning from 2006 to 2015, concluded that “the UK is dependent on EU funding to a concerning level”, said Daniel Hook from DigitalScience, speaking to The Guardian in May 2016 3. The report found that information and computer systems, the area of research with the most funding in the UK, received 40% of its funding from the EU, while psychology and cognitive sciences received 25% in EU funding. When looking at the distribution of EU funding across the UK, some areas received as much as 86% of their funding from the EU.

The UK government is failing to keep up with average contributions by other countries into research: the average spent on research as reported by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is now 2.4% of GDP, but according to the organisation the UK spends just 1.7%. However, separate figures from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics find that this number was actually below 0.5%, which followed the freeze on the science budget in 2010, and as recently as March 2015 this figure was still at 0.48% of GDP 4

UK science is essentially being carried by EU funding and, if access was removed, it could be a disaster, as UK institutions may struggle to keep up with the global standard. Sadly, it doesn’t even seem likely that the UK would be able to negotiate much access after we formally leave, with only 7% of funding reaching non-EU members during the last 10 years. In the end, the deficit in funds is likely to lead to much fewer positions being available within research institutions, and especially so within academia where PhD graduates are already finding it hard to find work.

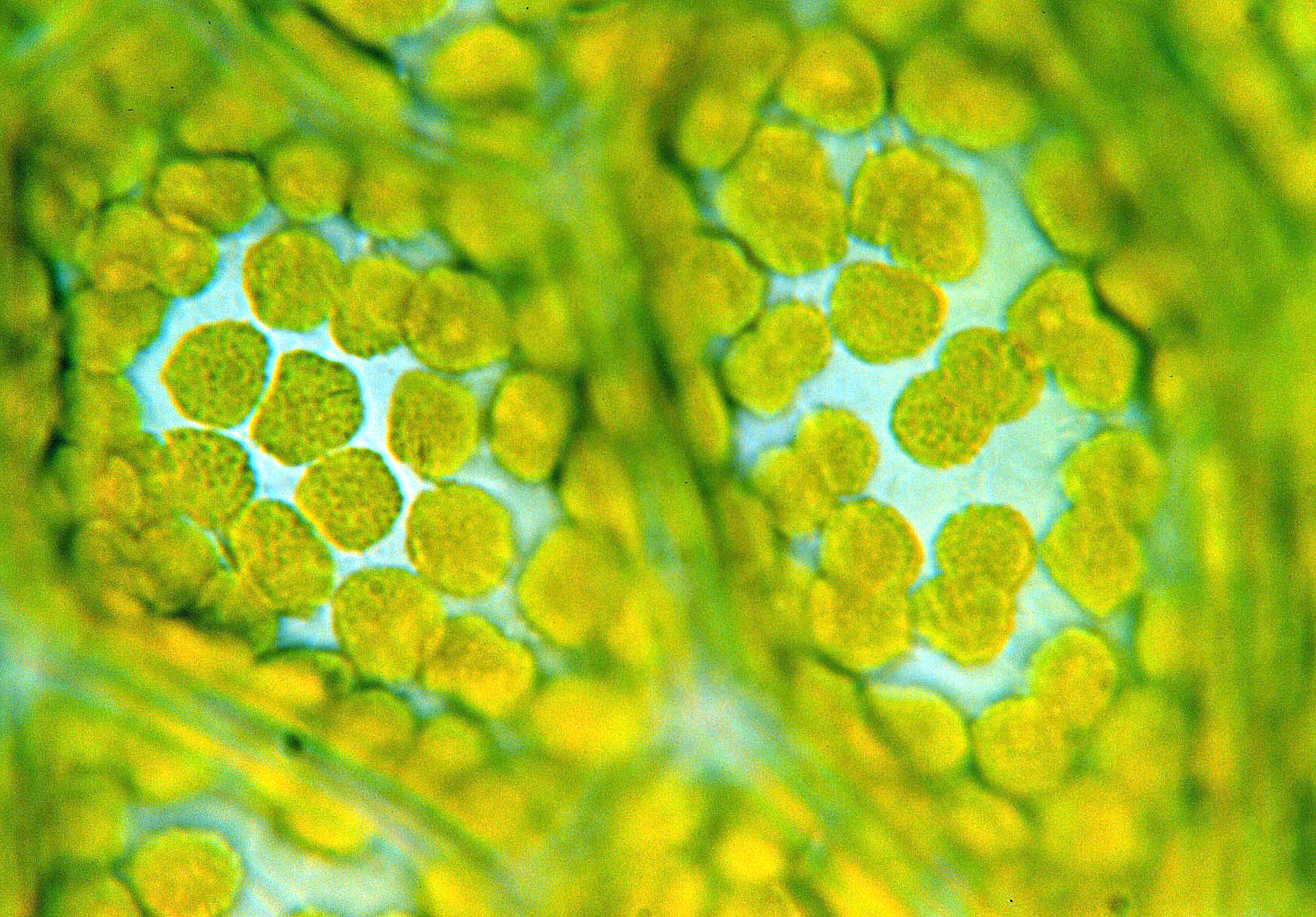

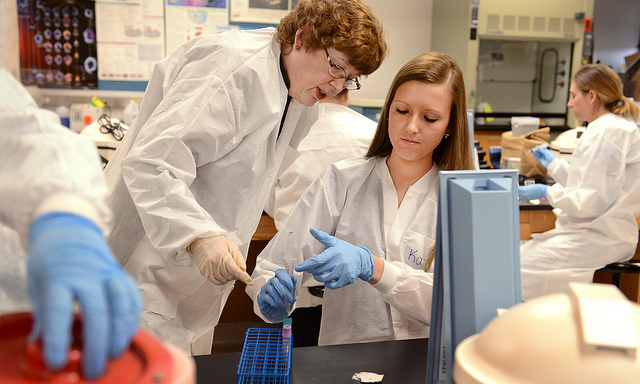

Universities may be left with less funding for research students Credit:Illinois Springfield via Flickr

The free movement of people within the EU, encouraged by schemes such as Erasmus, has been a blessing for both collaboration and in attracting the brightest sparks of their fields to UK institutions. If the deal made by the UK with the EU removes free movement, not only could it make it more difficult for UK researchers to work abroad, but universities and research groups would find it much harder to attract scientists at the top of their field to come and work with them. Many may instead simply opt to work in another European country where they can arrive and begin working almost immediately.

Even with the reduced feasibility of finding work in the UK becoming ever more likely, it is also possible that people may simply not want to live here after some of the recent debates in the referendum and the issues that emerged were at many times targeted towards immigration. Ewan Birney, the co-director of the European Bioinformatics Institute, speaking after the result said that the UK could still try and get access to big funds such as Horizon 2020 during the negotiations, but that there was a great sense that migrant workers are not wanted by people in the UK; “The overall mood which Brexit sends – that foreign nationals are not welcome – will I think be a deterrent to the top people coming here” 5. Understandably, if you were choosing to move your entire life to a new country, you would probably choose one where you felt like you would be more accepted.

Of course all of the negative impact on research and development could potentially follow on to other industries down the chain, such as environmental work, tech, and healthcare, creating a ripple effect. However, the biggest cause of worry for UK science is that we just don’t know yet. While negotiations are made between the EU and UK for the next two years, business is said to be largely as usual, but it will be how much access we still have to Europe, and whether the government plans to replace any losses in funding, that will decide how hard hit science is.

As a final note, it was disappointing to see how little the impact Brexit could have on science was featured in the referendum debate, as it was probably something that many readers of the GIST may have liked to hear discussed more. It is the indiscriminate, multicultural nature of the scientific community that makes it so admirable, and that personally makes me so grateful to be a part of it. Unfortunately, the issue seems to have gotten lost amongst heated discussions about sovereignty and immigration. As the fallout continues to cause one of the largest upheavals of UK politics in recent history, the outlook for UK research is simply becoming more and more uncertain. It is possible that something will be worked out to replace some of the lost funding, or the deal made with the EU might still include membership to the Schengen Area, but for now we simply don’t know, and we may not know for months, if not years, to come.

This article was specialist edited by Derek Connor and copy edited by Jessica Bownes

References

- https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/projects/uk-research-and-european-union/role-of-EU-in-funding-UK-research/

- http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/economic-impact-on-the-uk-of-eu-research-funding-to-uk-universities.aspx

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/may/18/brexit-would-threaten-world-class-british-research-major-report-warns

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/occams-corner/2015/mar/13/science-vital-uk-spending-research-gdp

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/jun/24/brexit-big-blow-to-uk-science-say-top-british-scientists?CMP=twt_a-science_b-gdnscience