The Conservation Beauty Pageant

I will be the first to admit that I am a fan of all things cute and cuddly. Send me a snow leopard adoption pack any day of the week, but a spider conservation trust? No thank you! We have an astonishing array of creatures and all of them contribute towards the big ecological system that is planet Earth. Yes some of them may be slightly aesthetically challenged, but does that mean we should ignore their plight? I have decided to dive into the murky realm of endangered species appeals, and I’m hoping you will join me.

Animals most often used in campaigns are named ‘flagship species’ due to their heightened status and public appeal. The support gained for these animals often benefits the ecosystems they inhabit, and by extension, the other animals, plants and people that live there too. There is no one list of flagships though, with choices varying from country to country depending on which species are the most high profile in that area. The work done to raise awareness for the plight of these animals is truly astonishing, but if we don’t widen the net, are we in danger of letting other species in trouble slip through?

All of these species are endangered, how many do you recognise? From top left: Banggai Cardinal Fish, Blue Whale, Abbot’s Booby, Egyptian Vulture, Pygmy Hippopotamus, Echidna, Golden Arrow Poison Frog, Fishing Cat, Red Panda, Cuban Crocodile, Coral Reef, Gharial. konjure via Flickr

This brings us to a rather important point: funding for conservation projects heavily depends on donations from the public. In 2013 alone, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) received almost US$87 million in individual contributions. Big hitters like WWF have a glut of animals ready for you to fawn over, but no mention of the blob fish, gob-faced squid or the UK’s own Fen raft spider. Yet these species are just as vulnerable as their loveable counterparts; just not so charismatic in photographs. Indeed, the blob fish is thought to be threatened with extinction due to the activities of ocean-bottom trawling. This proclaimed ‘ugliest animal in the world’ has just become the mascot for the Ugly Animals Preservation Society, a comedy group determined to raise funds forcreatures that are down on their luck. They need all the help they can get too, with most conservation charities preferring to focus on charismatic animals, such as tigers and whales, that draw the public eye. Additionally, research concerning the less-charismatic animals is rarely undertaken, due to the extreme lack of support from funding organisations.

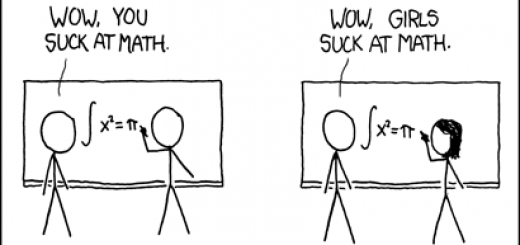

Public perception

Studying interest in different animals on Twitter suggests that there is a bias towards mammals, and larger animals in general 1. The polar bear is the obvious most-tweeted species, due to its status as the flagship representative of climate change. Who could ignore the sight of a polar bear cub on a melting patch of ice?! Other scientific research suggests that the threat status of the animal involved has absolutely no bearing on its likelihood of being chosen as a flagship, in favour of what appeals to the public most 2. Thus, we may be missing the opportunity to raise to the fore more endangered animals that belong to more diverse habitats.

This same group identified a potential 178 more so-called ‘Cinderella’ species, based on the same features which made their high-profile counterparts so appealing. The difference is that these animals are classified as critically endangered (the highest category for any at risk species), rather than vulnerable (like the polar bear). As their name suggests, the team think that these could be used as the new front runners in public campaigns; all they need is that wave of a marketer’s wand! Such schemes have worked before, like the Ugly Animal Awards (mentioned above) in which people voted for the ugliest animal on earth, encouraging the public to celebrate these animals warts and all. Yet however feasible this may be, the group speculate that they would not raise as much money as our traditional flagships because they are relatively unknown to the nation. It seems as if Cinderella species won’t go to the ball after all.

An endangered proboscis monkey lamenting his unfortunate nose (albeit the recent target of the Ugly Animal Society’s campaigns). Peter Gronemann via WikiCommons ( License )

The dark side of beauty

The scientific community seems in a quandary with the flagship debate as a whole, with many papers being published on the topic this year alone. It seems that the use of flagships could have untold effects, even harming the reputations of related species. Such a scenario took place in an attempt to save two parrots in the Amazon in the 1980s 3. The Sisserou parrot was put in the spotlight, its gleaming purple and green feathers becoming the symbol of the Dominican Republic. Whilst its sister species adorned flags and stamps, the Jaco parrot was left in the shadows, unfairly blamed for raiding farmers’ citrus crops. Its bad reputation grew and soon it became the expendable other, despite being a well-liked species that was popular as a pet before the campaigns. While neither would probably be around today were it not for the Sisserou parrot’s flagship programme, conservation groups should now consider more carefully the implications of ‘branding’ animals in such a way. Similarly, the little-known red panda originally held the name of panda, but was relegated to being referred to as the lesser panda due to the popularity of its ‘Giant’ neighbours.

Even when we are conserving Flagship species there are problems. For example, zoos often take these large animals from the wild in order to breed them in captivity. Their offspring are extremely difficult to release back into their natural habitat, where meanwhile no effort has been put into actively saving their homes. As it is easy to breed tigers in captivity, more money is being spent on this captive endeavor which might be better served in maintaining the forests in which they live. If wild tigers were cultivated more in their natural habitat, the profile of the area would be substantially increase and might even be easier to save (and so on in this positive cycle).

A new dawn of conservation campaigns?

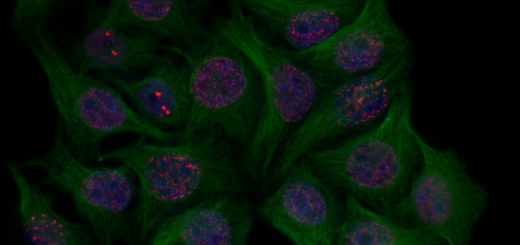

Current flagship campaigns do an excellent job of raising the profile of animals, habitats, and complex issues. They can work extremely well in today’s climate where budgets are stretched thin, especially for projects deemed ‘non-essential’. After all, we can’t possibly hope to save every animal in danger; there are simply too many! The Living Planet Report estimates that there has been a staggering overall decline of 52% in animal populations over the past 40 years alone 4. However, some would argue that we should be prioritising those animals that are scientifically useful or economically valuable. Equally, others feel the way forward is to systematically choose flagship species based on how ecologically important and genetically diverse they are, as well as whether they are appealing to the public, in an attempt to get scientists, marketing campaigns and projects to work together. Personally, I think animals should be conserved because they are fascinatingly complex, interesting and worthwhile, in spite of what they can provide us.

The age-old adage that one should never judge a book by its cover nonetheless serves its point. If we looked just a little deeper at these animals, we would see past their hairy legs and eight eyes, to something that serves a vital role in its environment. In fact they often serve a larger ecological role than current flagships, from the insects that pollinate our crops to the predators providing pest control. As a nation that usually loves to back the underdog, we may ask whether there is anything that can be done. The animals used in the Flora and Fauna International’s flagship species campaigns have been received with a great deal of success, including a range of reptiles, birds, invertebrates and plants as well as classic mammals. This gives us reason to hope that the success of campaigns doesn’t have to rest on whether the animal is cute or fluffy enough to provoke interest.

It’s hard work for scientists and conservationists to gain funds for animals that no one cares about. Therefore I urge everyone to get out there and explore the diversity of the earth for yourselves (online, in social media, tv, books, magazines, the list is endless); what you find may just surprise you. As for me, my own research has led me to the incredibly rare (and harmless!) Kaua’i cave wolf spider. This Hawaiian cave dweller has completely lost its eyes in the evolutionary process (so is sometimes referred to by locals as the blind spider) and there are only 6 populations thought to be left in the wild. It might give me nightmares to see in the flesh, but I certainly hope it stays around to inspire the next generation of spider enthusiasts.

Specialist edited by Vicki Smith and copy edited by Barry Robertson.

References

- Roberge J-M. Using data from online social networks in conservation science: which species engage people the most on Twitter? Biodiversity and Conservation. 2014

- Smith et al. Identifying Cinderella species: uncovering mammals with conservation flagship appeal. Conservation Letters. 2012

- Douglas LR, Winkel G. The flipside of the flagship. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2014

- Report from WWF: Living Planet Report 2014.