The future of COVID-19: an end in sight?

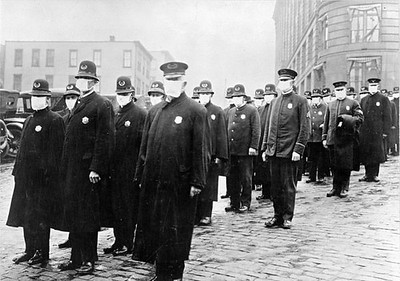

One hundred years ago, cities recovered from the final wave of the Spanish Flu. No other pandemic in modern history has had the potential to match its tragedy with approximately 50 to 100 million fatalities1. That is, until COVID-19 spread this year. The pandemic we find ourselves in now is not as unprecedented as often said, which becomes apparent when looking at the history of diseases. So by looking back, we might be able to predict the future.

What will the next year look like?

It is likely that 2021 will be similar to the past six months. To lower the fatality rate, social distancing, masks and other measures – also used during the Spanish Flu pandemic – will have to be obeyed to avoid hospitals filling up with patients2. Fortunately, the prospects of developing a vaccine are good; usually authorisation of vaccinations with clinical trials and production takes between 15 and 20 years3, yet there are currently 44 potential vaccine candidates already being tested on humans4. In the meantime, we can benefit from the additional protection of social distancing: other illnesses like the common flu and colds have extremely low transmission rates this year5.

Five years’ time

Since we may expect a vaccine in 2021, the following years will involve production and distribution6. A well organised distribution is key to control the pandemic development. Experts are trying to figure out how to reach the most efficient population immunity with limited vaccine production and resources.

Most likely, vulnerable groups such as frontline workers and immunocompromised people will be given access to treatment first7. That is, if the country which develops the remedy first makes it available worldwide and does not resort to ‘hoarding’8. The best case scenario is that by 2025 enough people will be immune to SARS-CoV-2 to stop the rapid infection rate characteristic of a pandemic.

Looking ahead to 50 years

Can we expect to reflect on COVID-19 as we do the Spanish Flu now?

The bad news is that following COVID-19, we may need to return to the lockdown lifestyle in the not to distance future. In the past, pandemics of this magnitude occurred roughly every century. But it appears that the time intervals in between dangerous viruses emerging are becoming increasingly smaller9. Many causes are contributing to this phenomenon, the main being the growing global population density and deforestation10.

As humans develop civilisations and travel in widely unexplored habitats, their contact with feral animals increases, providing more opportunities for viruses to jump from animals to humans. At the same time, disrupting ecosystems for urbanisation leads to the spread of animals like rats that carry many pathogens easily transmitted to humans11.

Hence, in preparation for future outbreaks it is crucial that governments reinstate preventative committees for pandemics. Beyond this, continued funding of research and development of laws addressing deforestation will be key to continued protection over the next 50 years. Otherwise, the chances are high of the next virus pandemic lurking just around the corner.

Edited by Alex Brumwell and Frankie Macpherson

References

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/03/how-cities-flattened-curve-1918-spanish-flu-pandemic-coronavirus/

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/dena-history-pandemic.htm

- https://www.health.ny.gov/prevention/immunization/vaccine_safety/science.htm

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker.html

- https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/08/how-will-covid-19-affect-coming-flu-season-scientists-struggle-clues

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-51665497

- https://www.rki.de/SharedDocs/FAQ/COVID-Impfen/COVID-19-Impfen.html

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01063-8

- https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/basics/past-pandemics.html

- https://edition.cnn.com/2017/04/03/health/pandemic-risk-virus-bacteria/index.html

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02341-1