Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it

The current COVID-19 pandemic shook the whole planet in a matter of weeks and changed our daily lives as we knew them. Changes like social distancing and lockdown have made us feel that this crisis is like nothing else we experienced before and while that is probably true for most of us, the planet itself has had its fair share of epidemics and pandemics from which we learned valuable lessons that we still use today.

1. The Black Death: The beginnings of germ theory and public health measures

The most devastating pandemic in history is considered to be The Black Death, which affected an estimated 30-60% of the population at the time1. The terrifying nature of the pandemic lay in the speed with which it claimed the lives of its victims with most people dying within two days to a week of developing symptoms. Most researchers now believe there were three types of plague at the time, each with slightly different symptoms – but all including a high fever. For the bubonic plague symptoms included headaches, painful joints, nausea, vomiting and the appearance of puss-filled tumours called buboes (hence the name ‘bubonic plague’). The second type was the pneumonic plague that affected the respiratory system resulting in the coughing of blood. The third type of plague was the septicemic plague which caused an infection of the blood resulting in multiple blood clots forming throughout the body and starving the tissue of oxygenated blood, forming purple skin patches.

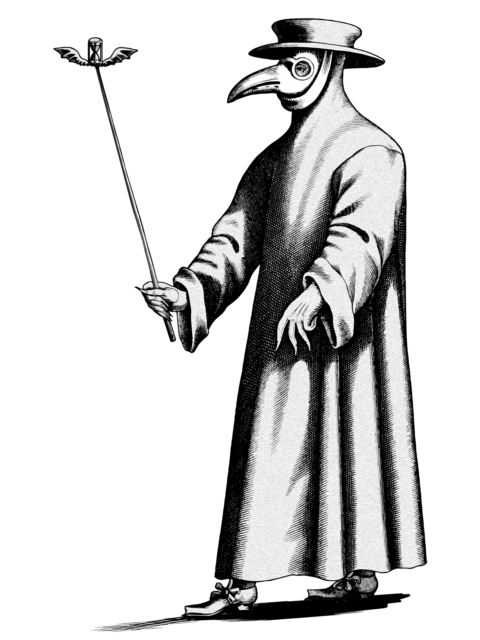

It is generally believed that the Yersinia pestis bacterium caused the Black Death but at the time the general public and medical staff were clueless about viruses, bacteria and how diseases spread. Even the concept of hygiene was incomparable to what we are used to today, with human and animal waste a common sight in homes or on the street. The most popular theory of spread and contagion at the time was “miasma theory” or “bad air theory” – claiming that poisonous air from sick (or decomposing) bodies was spreading the disease. Therefore, their method of avoiding contagion was to hold flowers, incense and fragrance in or around their nose to remove the “bad air”. This was so popular at the time that it became part of the plague doctors’ well-known uniform, with a mix of aromatic herbs and flowers being kept in the beak. Even though it wasn’t the actual smell causing the disease, they were right that many diseases are spread by being in close contact with a sick person (through germs from sneezes and coughs in the air or on contaminated surfaces) and therefore, “miasma theory” was a good precursor to the currently accepted germ theory. Despite the theory having its flaws, by removing the cause of the smell (for example the compulsory burial of bodies) they were sometimes inadvertently removing the bacteria that was causing the disease.

Doctors also advised fleeing to other cities or retreats where the air was clean. However, this was only possible for the rich, leaving the poor and middle class behind to suffer mass casualties. Unfortunately, some things never change and a parallel could be drawn to the health-inequalities surrounding the current COVID-19 pandemic where the rich ‘escaped’ to their second homes while the working class stayed at home and put their lives at risk by continuing to work in healthcare, food retail, delivery services and other key industries.

But on a more positive note, the Black Death also saw the introduction of public health measures at population level designed to control the spread of the disease, such as the introduction of the currently in use ‘quarantine’ method. Nowadays the excessive use of air travel makes us more susceptible than ever to the fast spread of disease outbreaks. Similarly, back then the plague was originally spread by merchants and their cargo travelling by sea from port to port2. Therefore, some cities banned strangers from entering if they had come from a town that had suffered an epidemic. Limits on public gatherings were also implemented3. Italy established a 40-day quarantine period that became the standard for the next 300 years4 (even the word ‘quarantine’ comes from the Italian word ‘quarantena’ meaning forty days). In some cases, infected houses were identified and quarantined for a fixed period of time. In other cases, the victims were sent to special, separate “hospitals” (called pesthouses or lazarettos) built outside the town borders and their contacts were traced and isolated.

At the time, medicine was helpless in the face of the plague, due to a lack of understanding of germs, bacteria and viruses or effective therapeutic interventions, but the above-mentioned public health measures became an important lesson on how to deal with and slow down an emerging pandemic, with most of these still being used today.

2. The case of Typhoid Mary: How carriers with no symptoms can spread disease

The story of Typhoid Mary is a great example of how an unaware carrier with no symptoms can cause a disease outbreak (or quite a few in her case). This famous case was described in detail by George A. Soper, a civil engineer from New York’s Department of Health that was hired to investigate a typhoid outbreak in the summer of 19065. The outbreak took place in the house of a New York banker, where his family of three plus seven servants lived. Six out of the eleven occupants got sick. In his search for the source of the outbreak, he considered “the overhead tank, the cesspool, the privy, the manure on the lawn, the food supplies, the bathing and the sanitary condition of the neighboring property to the people in the house”. Due to his past work on epidemics, Soper was familiar with the idea of ‘carrier people’ and through a process of elimination he came to suspect the cook, Mary Mallon. But how could the whole household become infected from the cook when the process of cooking should be enough to kill bacteria and make it harmless? Well, after using the toilet on a fateful Sunday afternoon, rather than washing her hands in the sink she instead, in the words of Soper, “cleansed her hands” in the dessert she was making for that night’s dinner, a dessert that did not need cooking – ice cream and peaches. Unfortunately, the cook was already gone by the time he figured this out…

Image Credit: Lupo via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-NC-ND- 2.0)

Soper completed some research through the agency that hired Mary and it turned out she had been responsible for spreading typhoid to a whopping total of seven households. The engineer managed to track her down after a few more of these curious outbreaks occurred at rich households that hired a cook. Unfortunately, she did not react well to his suggestion that she cease cooking forever or have her gallbladder removed to stop the spread (the bacteria that cause typhoid fever cling to gallstones). She was outraged at his accusations and insisted she never had typhoid nor gave it to anyone else. As a consequence, she was placed in an outside isolation ward. She eventually was released under the condition that she swore she would never cook again and would attend regular 3-month inspections. However, she quickly disappeared, breaking the promise and infecting several other people. She was later caught again and put in isolation in a little bungalow outside a hospital where she lived for the rest of her life. The total number of typhoid cases traced to Mary Mallon was 53, including 3 deaths, but there were likely many more. An important lesson can be learned from the case of Typhoid Mary which also applies to the current COVID-19 pandemic: asymptomatic individuals can be unaware that they carry a dangerous bug but can spread it to others rapidly.

3. The response from authorities during a pandemic can shape the spread of disease and the behaviour of the public

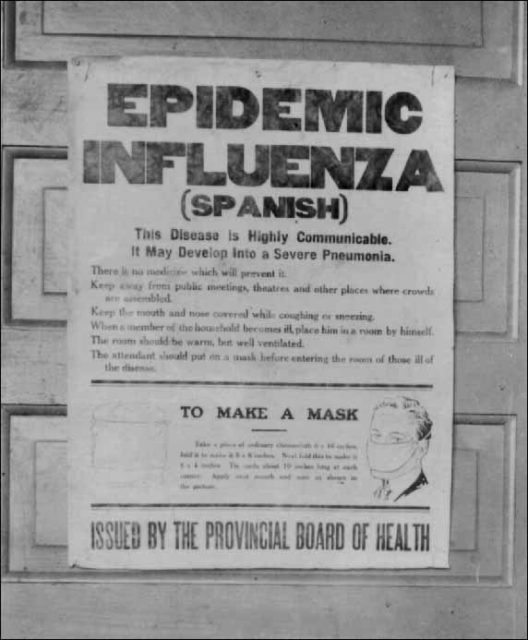

The Spanish flu hit the world in 1918 and infected approximately 500 million people (around a third of the total population at the time) with a death toll estimated between 17 and 50 million6. In fact, the death toll was higher than that of WWI. One of the biggest lessons learned from this pandemic was that the authorities’ response can massively influence the spread of an infectious disease and also the public’s behaviour.

Image Credit: Alberta Board of Health via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-NC-ND- 2.0)

Take for example Philadelphia, one of the hardest-hit cities in the US. As this outbreak happened at the end of WWI it first hit soldiers and through them travelled home to Philadelphia. However, this didn’t stop the authorities from holding a massive parade in which around 200,000 people took part. Three months later 13,000 people had died and hundreds of thousands got sick7. However, officials in another US city, St. Louis, responded in a completely different way which might have had a resounding effect on the spread of the disease in their area. They cancelled a similar parade and their death toll peaked at around 7008.

However, the Philadelphia authorities could be accused of more than just a lack of action – their lies and silence affected not just the spread of the disease but also the behaviour of the public9. Philadelphia authorities decided to keep silent, not print lists of the dead and to tell the public the disease was just the “same old fever and chills”. This strategy only inflicted terror and as a consequence, rather than listening to untrustworthy authorities, people started to believe horrific rumours and isolated themselves completely. People stopped coming to work, affecting the railroad system (needed for supplies), the telephone network (needed for communication) and the grocers (needed for food). People began starving to death because everyone was too afraid to bring food to the sick. In contrast, San Francisco officials printed a newspaper announcement on the full front page advising people to wear masks. Here, food continued to be delivered and the sick were still cared for. Furthermore, when the city police asked for 4 volunteers to remove “bodies from beds” 118 offered their help. The contrast between these two cities highlights how important the authorities’ honesty is for public health.

I like to think that we learned a lot from these pandemics and that these lessons have been applied to the current COVID-19 crisis, but there is always room for improvement. Similar to the public health measures set up during the Black Death we are currently on “quarantine” or ‘lockdown’. A few countries have closed their borders and most public gatherings have been cancelled or postponed around the world: Wimbledon, the Olympics and UEFA’s European Football Championship, to name a few. We also learned a lesson from Typhoid Mary which has been applied by many individuals who isolated in their homes despite not showing symptoms in order to protect those more vulnerable to the virus. Lastly, while the authorities eventually stepped up and cancelled big gatherings and enforced lockdowns all over the world their response was too slow. Only time will tell if the public felt the officials were trustworthy during the Covid-19 pandemic, but an increase in the number of people believing fake news makes me think the history of 1918 is repeating itself to some degree. What is for sure is that we are still learning and the current crisis will just make us better prepared for the next one!

This article was specialist edited by Ailish McCafferty and copy-edited by Rachael Sulaiman

References

- The Black Death: A History From Beginning to End. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IGKfDwAAQBAJ

- Lessons from the history of quarantine, from plague to influenza A. doi:10.3201/eid1902.120312

- Responses to plague in early modern Europe: the implications of public health. https://about.jstor.org/terms

- What caused the Black Death? doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.024075

- The Curious Career of Typhoid Mary. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19312127%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC1911442

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_flu

- The 1918 Spanish Influenza: Three months of Horror in Philadelphia. doi:10.5325/pennhistory.84.4.0462

- www.history.com/news/spanish-flu-pandemic-response-cities

- Avoiding the mistakes of 1918. doi:10.1038/459324a