What peer research brings to mental health science

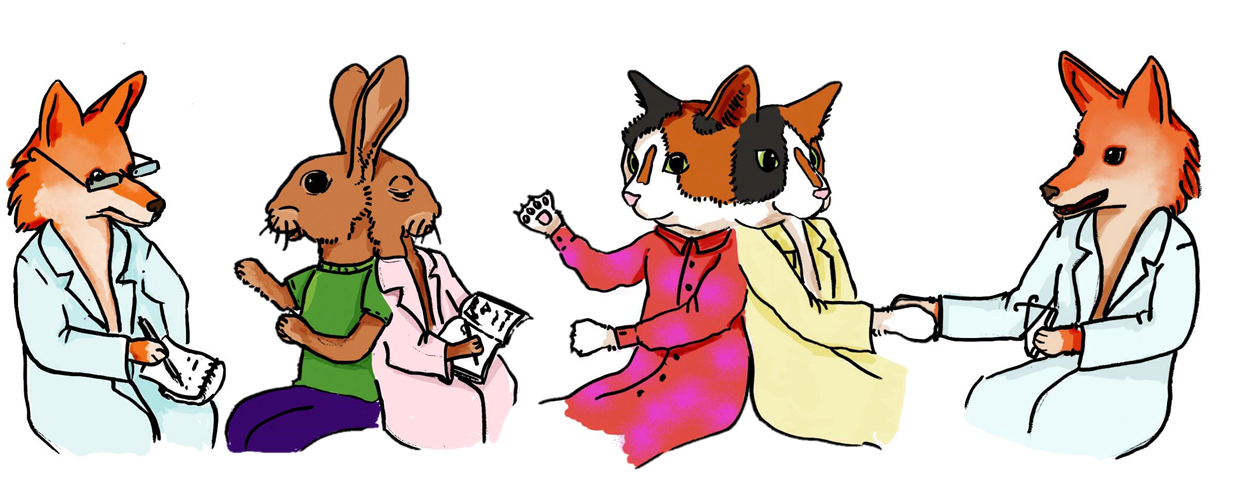

It is (probably) widely agreed that not all scientists wear white coats and work in labs. But, as highlighted in a previous theGIST article1, human beings often behave the same as those around them. When it comes to science, if we really do all do the same thing, this can have a powerful impact on what sort of research questions get asked and what science gets done. Research groups which prioritise diversity (including ethnic, gender, disability and academic background) were suggested by Nature in 20182 to be “more likely to pursue questions and problems that go beyond the narrow slice of humanity that much of science is currently set up to serve”. People who have experienced mental health problems may face barriers in the “traditional” route of undergrad, masters, PhD, years of postdocs and fellowships, and then becoming a principal investigator in charge of running clinical trials for serious mental health problems. However, this does not mean that people impacted by mental health conditions do not deserve a strong seat at the table when it comes to science concerning them

Beyond asking broader questions, a diversity of experience within a research group can have a powerful impact on how research in patients is conducted. Say you are in an A&E department receiving treatment following a suicide attempt. You are approached by a researcher who is developing a psychological intervention which might help, and they would like to evaluate this in a clinical trial. You consent to take part, so you sit down and write a “safety plan” as part of the trial. After filling it in, the safety plan that you created together with the researcher is handed to you. It is printed on generic paper. You are discharged, and the health service also gives you a plethora of papers about various medical stuff. It is likely, with what has just happened, that your mind might just be on other things. You then take the large bunch of papers home. A week later, a researcher calls and asks about the safety plan. You need to fish for it among everything else you were given on that day; sounds frustrating right?

What if someone with personal experience had been involved in designing the study? Having experienced treatment in hospital following a suicide attempt in the past, Suzy Syrett is aware of not being able to remember things clearly and just how much paper actually gets handed over to you following a crisis event. In her role as a peer researcher, she synthesises experiential knowledge into rigorous research methodology. The science of perception suggests that human beings notice items that stand out in some way even if their mind is exhausted. So, the safety plan is now in an unlabelled bright green envelope, which makes it stand out from everything else people are given post-discharge. Now, researchers can ask trial participants to look for their green envelope, and follow-up phone calls can carry on with the correct information to hand. This is just one recent example of the positive impact that Suzy has brought as a co-investigator on a clinical study. theGIST caught up with her to learn more about how she does science.

How did you get into being a peer researcher?

“I’m forty-six, and I’ve been under the care of mental health services since I was seventeen. I’ve spent a total of two years of my life as an inpatient in acute psychiatric wards and have written three books talking about my mostly positive experiences of engaging with mental health services – both as an inpatient and an outpatient. As a result of the books, I began giving presentations about my experiences, and it was at a conference where I was presenting that I met Professor Andrew Gumley. We talked, met a few more times, and then he asked me if I’d be interested in joining a study research team as an external consultant. He wondered whether my insights and reflections on my own experiences might play a beneficial role in ensuring that the needs of the participants in that study were being kept to the front of the team’s thinking at all times. I was fascinated by this idea and gladly accepted the invitation.”

How can being a peer researcher shape the science of mental health?

“In my opinion, the attributes that can make a peer researcher invaluable to the successful running of a clinical trial are as follows:

(1) To have the insight and self-awareness of which personal experiences have useful relevance to the study at that particular moment and why.

(2) To have a clear understanding of the various stages of a clinical research trial plus knowledge of individual roles and duties of the research team.

(3) An overarching motivation to ensure the needs of the trial participants are heard, and their voice is kept at the core of the research teams thinking at all stages of the trial.

(4) To have the confidence and ability to articulate and share our unique perspective in an informed and relevant way to shed light on any participant issues and use that perspective to help problem solve. Hopefully, this also broadens the awareness and insights of other members of the research team of what it is like to live with these conditions.

(5) The self-awareness, mutual respect and humility to accept that your lived experience is only one perspective and to always keep in mind that the experiences of other researchers working on a study can be different to yours while fully embracing that every single lived experience out there is just as valid as yours.”

Are there any challenges to being a peer researcher?

“I’ve had a few negative comments from some mental health professionals over the years, both due to their misplaced concerns that somehow working in mental health research would directly make me more unwell, but also some professionals looking uncomfortable when I tell them what my job is. Could that be due to a perceived shift in the patient/professional power dynamic? You’d have to ask them. I had some private concerns that my role might be treated as tokenistic by people in research teams I hadn’t worked with before, but I’m delighted to say that’s never been the case. While I’m aware this does happen, as not all academics are as accepting of the peer researcher role as they might be, I’ve been extremely fortunate with everyone I’ve worked with thus far. I suppose the elephant in the room that needs a mention as it has definitely got in the way of me being able to do my job at times is my own mental health issues. I had never worked before taking on that initial consultant job eight years ago, and, over time, a huge part of being able to be a peer researcher of the quality I expect from myself has been figuring out and accepting my limits. This process certainly isn’t just unique to me – I think everyone goes through it to some degree – but the long and short of it is I’ve learned that to do my job well, I need to ensure I have the time and space away from work to spend time with my husband, relax, empty my brain, catch up on sleep, see my psychiatric nurse and do all the things I need to do to keep myself well.”

“One of the massive benefits of the role – something I never expected or anticipated – is that it has given me the rare opportunity to reframe some of the more difficult and painful experiences I’ve been through in my life due to my mental health issues. To be clear, these experiences will always hold their weight of trauma and pain for me. But now, as I share them in meaningful ways in research studies and trials, there’s the hope that maybe, in a tiny way, they might be part of why someone else receives a treatment or benefits from a new finding because of an outcome from a research trial I worked on.”

You’ve worked across several clinical studies now. How has your role changed over time?

“It’s been amazing! And I think my progress and the growth of my role as a peer researcher is much more about the benefits the role brings to all aspects of clinical research trials than a reflection of anything particularly specific to me. The role started out as a fairly minor one and definitely in a more limited advisory capacity. That has changed significantly, and I now find myself involved in a myriad of ways from helping to write funding applications to qualitative analysis to improving methodology and how we communicate with our participants as well as being in increasing demand to become involved in other studies and trials.”

The role of the peer-researcher is an important one, and something that will hopefully expand as we realise its value. When science welcomes diversity, it may just result in research that more beneficial for everyone.

This article was specialist edited by Tuuli Hietamies and copy-edited by Sonya Frazier.