Diversity Challenge: Where are all the underrepresented scientists?

Diversity Challenge is the brainchild of Luke Kristopher Davis, a physics PhD student at UCL, Faith Uwadiae, an immunologist at the Francis Crick Institute, and Kayisha Payne, Associate Scientist at AstraZeneca and founder of BBSTEM. Like many of the rising stars of SciComm, they first met on Twitter.

Luke watched an episode of 2018’s Christmas University Challenge where Anita Anand, Zoe Laughlin, Angela Saini, and Anne Dudlet represented the alumni of King’s College London. He was left wondering why the show doesn’t have more teams that look like this, and he wasn’t the only one.

I love quiz shows, but I’ve always found University Challenge to be particularly pale, male, and stale. I was disappointed but not surprised when Wendy Bradley revealed in The Guardian that the teams aren’t chosen based solely on their general knowledge credentials, but that they must also be cast by producers. University Challenge hit the headlines after yet another all-male final in 2017; social media outrage ensued.

The producers seem to have learned from their public dragging over sexism; most teams in this year’s competition had at least one panellist who identifies as female (University of Edinburgh, York, and Darwin College Cambridge being the notable exceptions), but there were still 18 all-white teams competing.

And it isn’t just the panel after panel of young, middle-class, white men that’s grating. The subject matter has also been a cause for concern. Sure, the questions are about renowned scientists, engineers, artists, and composers, but they’re mainly about prominent men. The show has since attempted to redress the imbalance by asking more questions about women but has been met with complaints that the quiz is now harder. Of course it is. Minorities who have made great contributions to their field have long been overlooked by textbook editors and university course coordinators. And what about the racial imbalance – how many black and minority ethnic scientists did you learn about at school? I wasn’t taught about any.

In stark contrast is the premise of Diversity Challenge. Luke, Faith, and Kayisha wanted to create a quiz show featuring diverse science communicators but also to raise the profile of underrepresented scientists whose contributions are less well known. After gaining support in the form of Wellcome funding, they invited members of the public to submit questions (via Twitter, naturally) about their favourite black and brown biologists, women engineers, LGBTQ+ mathematicians, disabled nanotechnologists, and Asian and minority ethnic physicists. Angela Saini also showed her support by signing copies of her books which were awarded to two lucky people who sent in questions.

Luke created a question generator using the database of questions and random sampling. After weeks of fact-checking by the team, it was time for an epic crafting session involving yogurt pots, washing tablet boxes, and dome buttons. The dome buttons were inserted into the pots and connected to a Raspberry Pi (a small single-board computer, initially developed for teaching computer science in schools) through soldered wires and resistors. And ta-dah! Players would now be able to buzz in when they think they know the answer.

The quiz would be hosted by Suze Kundu, a nanochemist (“by trade and quite literally”), writer, presenter, and head of public engagement at Digital Science (you might know her better as @FunSizeSuze on Twitter). But before the competition kicked off, we had a series of talks from invited speakers.

First up was Siena Castellon, an autistic, dyslexic, and dyspraxic 17-year-old with ADHD. She told us how she had been “lulled into believing that sexism and misogyny were a thing of the past” but was bullied and dismissed by her teachers and peers at King’s Maths School. She was ridiculed both for being a girl and for being neurodivergent. Despite STEM being well suited to the strengths of many people with autism, Siena was treated like she was defective. Her teachers tried to prevent her from sitting the AS economics exam. In emails Siena released on Twitter, her teacher stops just short of accusing her of “cheating” in class tests but diminishes her hard work. Other students were not treated in this way – her teacher just couldn’t believe that someone like her could perform well in an exam on her own merits. Siena had to sit the exam as an external candidate at another college. She got an A.

In other words, if I did well it didn’t count. What’s worse being the only student in the class told I was not “allowed” to take exam or having my hard work / knowledge discredited by an accusation of it being “cheating” when I simply took the exam the teacher designed & gave us? pic.twitter.com/PZfZnLEre6

— Quantum Leap (@QLMentoring) October 3, 2019

Having a wealth of experience in advocating for herself, Siena founded Quantum Leap Mentoring to support other young people with learning differences. She is the creator of Neurodiversity Celebration Week, the first of which will be the 16th-20th of March, 2020. Siena had a negative school experience due to her differences, and she isn’t the only one. With 15% of UK students having a learning difference, Siena wants schools to stop focusing on what those children can’t do and start to acknowledge the positive aspects of neurodiversity. She urges us all to confront the biases we may have about people who are different to us.

Next we heard from Charlie Wand, a bisexual trans chemist/chemical engineer. He told of the frustrating double-standards LGBT+ people can face, such as being told not to “shove” their sexuality into colleagues’ faces at work, while having to listen to the same (straight) colleagues talk about their spouses with wedding photos proudly displayed on their desks. Many don’t feel comfortable enough to be out at work, but hiding your true identity can also take up a lot of energy. He pointed us to a report by the Institute of Physics, Royal Astronomical Society and Royal Society of Chemistry which found that 28% of LGBT+ respondents had thought about quitting their job because of the climate or discrimination.

We then heard from Madina Wane, a PhD student at Imperial College. She told us how excluding underrepresented groups in science and innovation can actually compromise safety. An excellent example of this is crash test dummies; they’re man-sized, and, as a result, women wearing seat belts are 47% more likely to be seriously injured in a car crash than men are. Seat belts were introduced in the 1960s, so why is it that today these inequalities still exist? ‘Female’ crash dummies exist but they are just ‘male’ dummies scaled down – and they’re usually put in the passenger seat. Who is involved in research and innovation matters. If you want to find out more about this, I’d recommend reading Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez.

Elli Harpum told us that she always wanted to be a physicist despite not having any scientists in her family. She’s faced numerous obstacles. At school, she was told by a teacher that she was crap at maths (the same teacher that gave the boys extra lessons). After accepting a PhD position, she was told that she couldn’t do experiments in a wheelchair – this effectively stopped her from doing the PhD. She was then informed that her supervisor didn’t want to work with her anymore because of this (which is illegal, by the way). She’s had very different experiences at different institutions and now has a PhD at a university where she is fully supported.

Lastly, we heard from Abbie Bray about her impostor syndrome. The first in her family to get GCSEs, she was told by a careers advisor that she couldn’t handle university. She, like a lot of working class people in academia, spends a lot of energy masking her accent. People make assumptions about her, and at various events she’s been mistaken as a secretary and even as a sex worker. She believes university staff need training on impostor syndrome and how to best support students from working class backgrounds. Impostor syndrome can be brought on immediately if students feel like they’re just there to meet a quota.

Abbie’s experience made me wonder how much of impostor syndrome is self-doubt and how much is being surrounded by people who make you feel like you don’t belong. The overwhelming message from all of the speakers was that those from underrepresented groups need to do a hell of a lot of extra work to participate in science. Why are so many people being excluded?

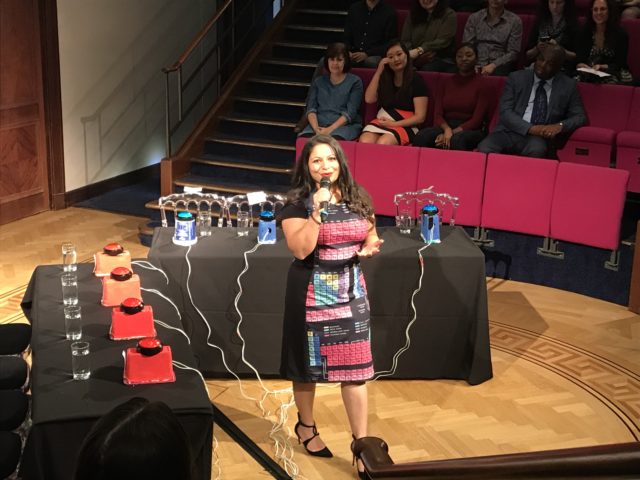

Suze Kundu takes to the floor (rocking a periodic table-print dress), and it’s time for the teams to go head to head – who would have the most diverse STEM knowledge? Suze welcomed the audience to the Royal Institution and introduced the teams.

On the red buzzers was team captain Chris Jackson, a TV presenter and earth scientist at Imperial College. He was joined by Alfredo Carpineti, an astrophysicist, science journalist, and founder of Pride in STEM, Jessica Boland, a lecturer of functional materials and devices at the University of Manchester, and Lakechia Jeanne, a biomedical scientist and founder of Girls In Science.

The blue team was captained by Natalie Cheung, a civil engineer who was awarded the YMCA Young Leader of the Year 2018 and University of Manchester Medal of Social Responsibility in 2019. Her teammates were Nira Chamberlain, a senior data scientist, mathematician, and the president designate of the Institute of Mathematics, Esther Odekunle, a senior scientist at GlaxoSmithKline and science communicator, and Cathy Abbott, a neurogeneticist at the University of Edinburgh.

“Who was the woman behind the famous HeLa cell line? No conferring!”

CATHY ABBOT BUZZES IN

I was worried this would feel a bit like an exam, but I began to relax – at least I knew the first answer.

If you only read one pop-sci book this year, make it The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot. Henrietta was a black woman whose cervical cancer cells gave rise to the first immortal cell line and revolutionised medical research. Her story was absent from history books for many years, with some textbooks even referring to her as Helen Lane. This was illustrative of how black and minority ethnic people’s contributions to science were overlooked, or even erased, by influential white scientists.

Her cells were taken in 1951. Another 45 years passed before the first annual HeLa Women’s Health Conference was launched to recognise “the valuable contribution made by African Americans to medical research and clinical practice”. But since then, have things really changed? Several studies show that racism in academia is still rife. In February, 2019, there were over 12,000 white male professors working in UK universities. The number of black British women with that title? Twenty five.

10 POINTS TO TEAM CHEUNG

The questions did get harder from here but both teams excelled. Every science student knows about Newton, Einstein, and Edison – I dare any University Challenge team to go up against these contestants.

The event was fresh and exciting with a nail-biting finish where Team Cheung were only just pipped to the post. I looked around; the whole audience were on the edge of their seats.

You might think that the contributions of underrepresented scientists being omitted from history is, well, history. But why is it that in 2019 a true representation of current student populations is being obscured from our TV screens? Diversity Challenge would make riveting TV – the homemade buzzers only added an extra layer of drama. I think we can agree that the University Challenge selection process is out-of-touch if it’s lagging behind comedy panel shows in the diversity stakes.

If the availability of diverse student communities isn’t the issue, what exactly is causing this imbalance? Producers can claim that women, LGBT+, and BAME students aren’t putting themselves forward for auditions, but it isn’t enough to just state that you welcome diversity. What are you actually doing to make people from underrepresented groups feel welcome? We all have a responsibility to make everyone feel included.

The organisers of Diversity Challenge showed just how rewarding it is when you make that extra effort. It was so much more than a game show. The night was exciting and educational (I even got a bit emotional). It doesn’t matter if you don’t know all the answers – nobody gets all the answers on University Challenge either. But it’s everyone’s responsibility to learn about underrepresented scientists and to educate ourselves and others. Most importantly, the event was a call to action, showing just how much more we all can do for equality, diversity, and inclusion.

Luke has made his question-generating code publicly available via GitHub. Where will the next Diversity Challenge event be held? Watch this space….

Twitter: @DiversityChall

The organisers of Diversity Challenge would like to thank all those who have helped with the project in any way.

This article was specialist and copy-edited by Sonya Frazier.