AI and mental health: big data and feelings

We have just survived Blue Monday. Apparently, the most depressing day of the year. According to the un-named ‘researchers’ quoted in every tabloid, Blue Monday is the day when, on average, we are the loneliest; feeling most overwhelmed by the weather and mentally crashing hard after the high of the holidays. This was supposedly calculated using a ‘formula’ taking into consideration weather, debt, stress levels, time spent relaxing, time since failing New Year’s resolutions etc. However, a quick google search will take you to numerous articles debunking it, calling it a commercial scam and highlighting how it is hurtful to people who suffer from mental health issues all year around. Bottom line being: mental well-being determination using such a simple formula is a hoax. The idea of being able to calculate the possibility of feeling low sounds good in theory, but it is not that easy or straightforward. Each of our life experiences are so very different, and we respond to our environment so variably. Therefore, a simple formula just won’t do, and estimating our mental well-being mathematically is still a great challenge. An algorithm to tackle this problem would have to be much more complex and able to adapt to ever-changing circumstances. This algorithm would have to be intelligent like a human, and powerful like a computer. Luckily, computer scientists have been working on something exactly like that for the better half of the last century.

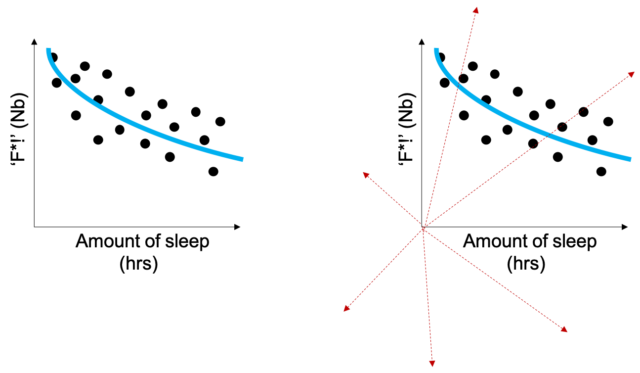

Artificial intelligence (AI) is essentially decision making performed by a machine that has been designed to mimic human intelligence by learning and solving problems. One branch of AI, machine learning, can be used to collect data, learn from it and predict future events based on it1. Why is it so promising? It’s the AI’s superior ability to process large amounts of data in a very short time. The human brain can easily process data in two dimensions (2D), however, AI can do it in hundreds. Here is an example: we could collect data and try to correlate the amount of sleep you’ve had the night before (to sort of pseudo-represent your physical well-being) to how you feel the day after (represented by, let’s say, the number of times you used swear words the following day). If we collect a sufficient amount of this data and plot it in a graph like the one on the left-hand side, we might see a curve correlating your general irritability with the lack of sleep (i.e. the less sleep you get, the more f-bombs you drop).

Credit: Anna Andrusaite 2019

If this curve is accurate, and a correlation exists, you would be able to predict how irritable you will feel just by how many hours you’ve slept the night before. This example is a 2D analysis of a data set that can be easily analysed by the human brain (i.e. one dimension is the amount of sleep, the second one is the amount of ‘f*s’ and ‘sh*s’). But what about all the other factors contributing to your irritability? AI could analyse correlations in hundreds of dimensions, as shown by the graph on the right and additionally also process images (i.e. the bags under your eyes). Furthermore, it can learn and adapt. If your New Year’s resolution was to stop swearing altogether, it could still predict how much you’ve slept based on the numerous other sets of data – for example, the number of times you’ve rolled your eyes at your annoying course mate. Simply put, AI is potentially a wonderful tool that can be used to understand our mental well-being patterns and process huge amounts of data very quickly. Most importantly, it can improve along the way, just like humans. Well, at least in theory.

Why is it important to understand what affects our mental health? Understanding something allows us to use it for our own benefit. Can we use all this knowledge about mental health to help others? Yes, we can, and therapists have been doing it for years. Counsellors use various techniques to help people develop tools to improve their emotional regulation. One of the most commonly used approaches to tackle psychological issues, such as anxiety and depression, is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). The general idea of CBT is to apply well-studied strategies and ideas to each individual patient and their experiences in order to improve their life quality and coping mechanisms. With society slowly clamping down on the stigma surrounding mental health, it has become more and more apparent that most people would benefit from some form of therapy at some stage in their lives. However, most people might not have the resources, time, or the privilege to be able to sit down with a therapist every couple of weeks. AI researchers and developers might have a solution for this. What if you had a therapist in your phone, accessible 24/7, always listening, never judging? As discussed in a recent article by Michael Rucker2, there is an increasing amount of platforms utilising AI to deliver therapy directly to your phone. Some are AI-based systems that resemble chatting with someone online, such as Tess3 or Woebot4. These AI operated platforms learn about you and your feelings, to be able to offer evidence-based CBT tools. However, others like Ginger.io5 integrate both AI and real therapists to offer a synergistic platform of support. This joint approach might be more reliable for the time being because, while there is a lot of promise in these technologies, no AI platform can fully mimic human interaction. It does not have a mind of its own, and it is likely to misunderstand social cues.

Additionally, AI can be used indirectly to aid your mental well-being. For example, scientists are using AI to try and predict depression based on social media activity and language used in Facebook posts6. The general idea of the project was to train AI using hundreds of thousands of Facebook posts from depressed and healthy people. After the AI was primed, it could detect cues of depression-like language in posts months before people were medically diagnosed. Studies like these could be very beneficial as early detection can increase the effectiveness of treatment for depression.

As per usual, with great power comes great responsibility. What about privacy policies and data protection? We could be one mistake away from making already vulnerable people even more vulnerable. Also the enormous risk of medical misdiagnosis in the context of both our health and the legal aspects associated with it has to be considered. Who would be liable if something goes wrong? At the end of the day, it has to be safe. There are a lot of hurdles yet to be jumped. Nevertheless, AI as a tool for studying, assessing and improving mental health services is indeed very promising. It would be a wonderful tool that could potentially help people who are not able to speak to others directly, but who are, however, in need of the interactions. The possible benefit of providing mental health assistance directly to people’s phones sounds very convenient indeed. And also, much cheaper than conventional mental health care. But will it ever completely substitute human interactions? Probably not. What if it takes a human mind to help another human mind? Maybe, AI can never fully ‘understand us’.

This article was specialist edited by Kym Bain and copy-edited by Laura Kane.