Can We Give Biotech the Green Light?

The Victorian Bar at the Tron Theatre is perhaps not the most likely place to go for a passionate debate about science on a Monday night, but Glasgow Café Scientifique is all about getting science out of the lab and into society; giving the public a chance to engage with scientists in an informal setting where their questions and opinions will be heard. At this special Café Scientifique event as part of Glasgow Science Festival, we met three experts in the field of biotechnology, and heard how this cutting-edge science can have a place in a ‘green’ Scotland.

What is biotechnology?

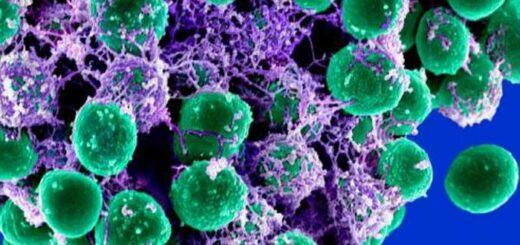

Biotechnology is about using biology to solve problems facing our health and planet. This ranges from using microbes to make useful products like medicines, to developing crops and livestock to improve food supply or sustainability. An important part of biotechnology is using genetically engineered microbes, plants and animals to take advantage of solutions already ‘invented’ by nature. Biotechnology researchers take these solutions and make them more efficient or apply them in new ways that can benefit society.

The experts

Dr. Louise Horsfall is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Edinburgh. She explained how she’s trying to genetically engineer bacteria to mop up metal ions from liquids or soil and package them into stable nanoparticles, to be used as catalysts or antimicrobials. This approach can be used to clean up copper waste from alcohol production – an important issue in the home of the whisky industry – or decontaminate plants used to absorb metal ions from polluted soil. Horsfall thinks biotechnology is about making something useful at every step of the production process, so nothing is wasted.

Prof. Helen Sang is a research professor at the Roslin Institute, birthplace of Dolly the sheep. She told us about her research on genetic modification in chickens, which she believes will become an increasingly important protein source as the world population grows and the sustainability of red meat is called into question. Prof. Sang described research that aims to engineer a bird flu resistance gene into chickens. The gene mimics a small part of the flu virus and stops it from making copies of itself, so it can’t spread. Prof. Sang wants to see a widespread acceptance of genetically modified (GM) technology so we can use it to tackle animal disease on a large scale.

Dr. Donald Bruce is an ex-nuclear energy researcher who now runs an independent consultancy on the ethics of emerging technologies. He has advised on the ethics of many biotechnology developments including GM crops, cloning and genome editing. He spoke about the case of Zeneca’s GM tomato purée, released in British supermarkets in 1996. The better tasting, cheaper product was clearly labelled as GM, and was broadly accepted until a media backlash changed public opinion. Bruce believes that public support for GM depends on the balance of perceived risks and reward, and that this varies for different applications.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/coreytempleton/14138686480

Image credit: Corey Templeton via Flickr

After hearing from the panel, the floor was opened to the audience for a lively debate…

What is the biggest barrier to GM technology, and how can we overcome it?

Following on from his introductory comments on risk and reward, Bruce suggested that the biggest barrier is that the western public can find it difficult to see the overall benefit to many GM products, especially in the case of food supply. When they weigh the benefits against the perceived risks (to health and to the environment), they don’t see a net gain from using the technology. So we need to either reduce the perceived risk, through long-term research and education, or increase the benefit, for example by making GM products a cheaper alternative. What if we used GM in areas where it’s easier to see the immediate benefit, like in medicine? Prof. Sang pointed out that biotech already is more accepted when it’s used to treat disease. ‘Biologic’ medicines like the breast cancer drug Herceptin are made using genetically engineered cells. New gene editing technology has recently been used to treat leukaemia. Progress in these areas will hopefully help to highlight the benefits of genetic engineering and open the door to other applications.

What role have the press had in the public perception of GM?

A huge impact, according to Donald Bruce. A 1999 campaign by Greenpeace, other NGOs and the UK press systematically destroyed the public’s faith in so-called ‘franken-foods’. The ‘mad cow disease’ epidemic throughout the nineties didn’t help – even though it had nothing to do with genetic engineering, it made the public wary of what they were eating and mistrustful of government recommendations. Even now, the media have a requirement to be balanced, even when the majority of scientific opinion supports one side. While there is no scientific evidence for harm to health so far, the negative attitudes persist.

Are regulatory restrictions hindering our use of genetic engineering?

The experts explained here that although genetic engineering is allowed in research, GM crops require approval from the European Food Safety Authority before they can be grown on EU soil. Currently very few crops have approval, and member states can opt to ban their cultivation on an individual basis. Interestingly, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all have a complete ban on GM crops, but England does not. Horsfall explained that this reluctance doesn’t stop at food crops – an arsenic-sensing GM bacterium that can identify contaminated drinking water has been awaiting approval from the European Commission for four years. Coming back to the risk and reward concept, this technology does not have obvious benefits in Europe, but could be lifesaving in poorer regions of India, Bangladesh and Nepal. Dr. Bruce commented that “If it’s not acceptable in Europe then we shouldn’t have it” is a misleading idea – we shouldn’t stop other countries from adopting solutions that are appropriate to them.

So what have we learned? Biotechnology and genetic engineering have many uses, some of which can clean up the environment or improve sustainability. The question is not “How is genetic engineering bad for the environment?” but “How can it be applied to help us achieve our environmental goals?” Yes, government policy prevents the use of GM technology, but this is based on public opinion and a misguided attempt to protect Scotland’s ‘green’ reputation.

It’s the public we need to convince if we want to use these technologies ourselves, but even that shouldn’t stop us from developing tools and solutions for problems further afield. And how do we persuade the public? With open and intelligent debate like we’ve heard tonight. Another Glasgow Science Festival success.

Glasgow Café Scientifique is a regular event that runs on the first Monday of each month: http://www.gla.ac.uk/events/cafescientifique/

More information on ethical issues in genetic engineering: http://www.actionbioscience.org/biotechnology/glenn.html

Scottish Government page on GMOs: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/farmingrural/Agriculture/Environment/15159