Tale of the Tiny Chromosome

At some point in your life you will have met or known someone with Down’s syndrome. Every 1 in 800 people have an extra, tiny chromosome 21 but what exactly does this extra chromosome mean for them?

What exactly is Trisomy 21?

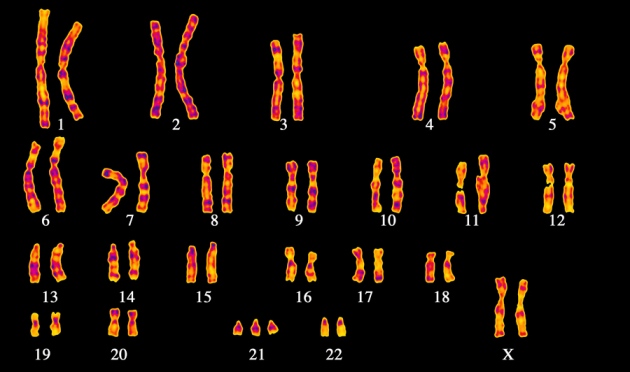

First described by John Langdon Down in the year 1886, Down’s syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by an extra chromosome 21, also known as Trisomy 21. Each of us are made up of 100 trillion cells which contain the code of life -DNA. The DNA, encoded in the language of the four letters A, T, G, C (known as bases), contains every recipe needed to make the proteins and everything else required for a functional individual. These long stretches of DNA in every cell are condensed to a great extent and divided into chromosomes, each with different sets of genes. Our species of humans have a total of 46 chromosomes, in 23 pairs.1 Any addition or deletion of any of those 46 chromosomes will lead to an excess or deficiency in certain genes (genes are nothing but DNA!), and there are consequences for these additions and deletions. Disorders such as Huntington’s disease occur when there are too many bases in a particular gene but what about if there is an entirely extra chromosome? Most foetuses end up still-born or in early miscarriage. Only an excess of chromosomes 21, 18, 13, and X are viable.

Spectral Karyotype of a female with trisomy 21. Image credits: http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2014/03/01/marthe-gautier-another-woman-scientist-trivialized/

What are its features?

Babies born with Down’s syndrome have a characteristic face with a flat nasal bridge and single crease on their palms. They have delayed development with learning difficulties, and most also have speech problems and social/behavioural issues. Some also have hypothyroidism (an underactive thyroid gland), cardiac issues, and coeliac disease. Those born with Down’s syndrome are also predisposed to developing Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, with a small percentage having a risk of leukaemia.2

How does an extra chromosome 21 affect you?

Chromosome 21 is the smallest chromosome in humans, with around 200-300 genes, spanning 48 million base pairs. Ironically, most of these genes are not dosage sensitive. As we know, we have 2 copies of each gene called alleles; and evolution is so wonderful that most of the time, the cells can work with only one or even three functional copies. An excess or deficiency in the dosage of these gene products does not affect the cell. However, problems arise for genes that need both copies- this is called dosage sensitivity and these genes are haploinsufficient. The proteins made by these genes must be at their optimum level, with an excess or deficiency leading to cell dysfunction.3 Research has shown that an excess of only a few genes from that entire chromosome lead to most of the features associated with Down’s syndrome, and yes, those two genes are dosage sensitive. It is also intriguing that almost 50% of the people affected with Down’s syndrome develop Alzheimer’s disease by the age of 50.

But, where does that extra chromosome come from?

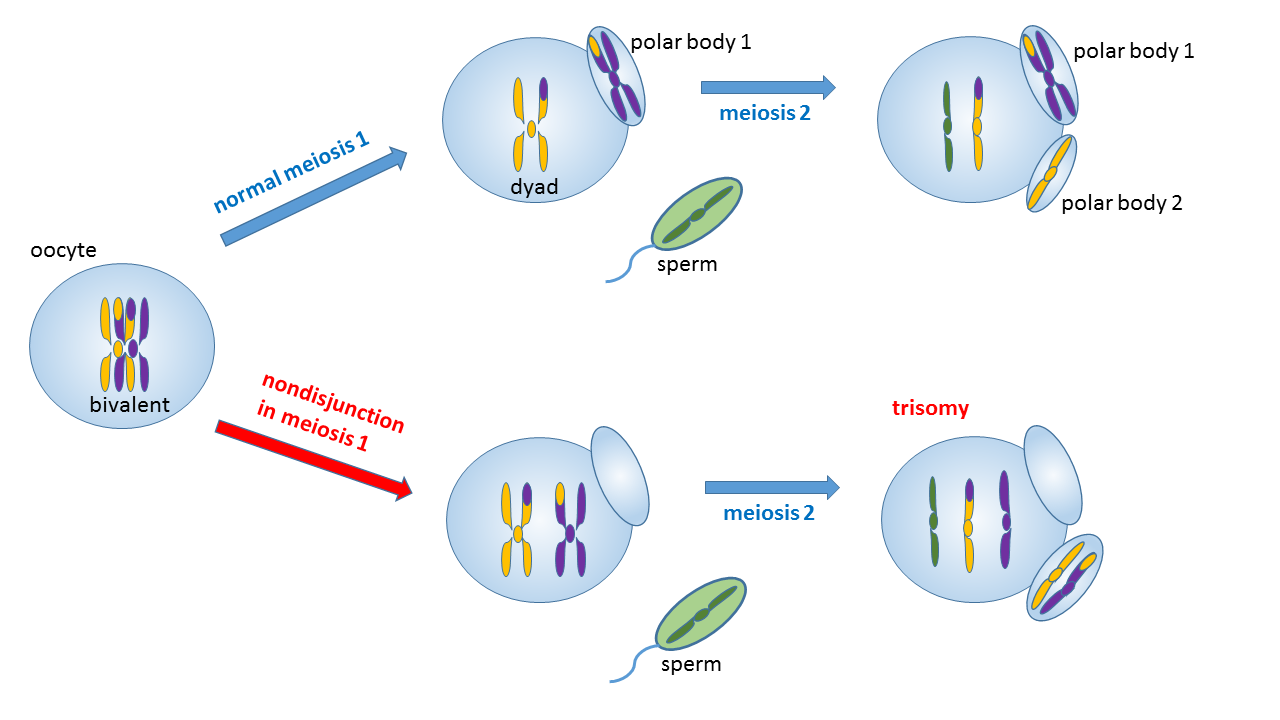

Out of the 46 chromosomes we have, 23 chromosomes comes from our mum, and the other 23 from our dad. However, a special type of cell division called meiosis (reduction division) occurs in our gametes, so that each egg or sperm will have only 23 chromosomes. This is nature’s way of making sure the number of chromosomes is intact in a species. Sometimes, however, during this division, the chromosome 21 pair doesn’t separate. This is called non-disjunction. If this happens in the mum, her egg will have two copies of chromosome 21 and when this fuses with the dad’s sperm (which has one copy of chromosome 21), the zygote ends up having three copies of chromosome 21. This divides to form a whole new life with an extra chromosome. This doesn’t always happen in the egg as the non-separation can also occur in the dad’s sperm. There are also people who have mosaic Trisomy 21: they inherently have two different cell lines, one with two copies of chromosome 21, while another have three. The effect depends on where all the trisomy 21 cells are present. These events are spontaneous, and hence one does not inherit Down’s syndrome in such cases.

Non-disjunction in an oocyte (egg cell) leading to trisomy. Image credits: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trisomy_due_to_nondisjunction_in_maternal_meiosis_1.png

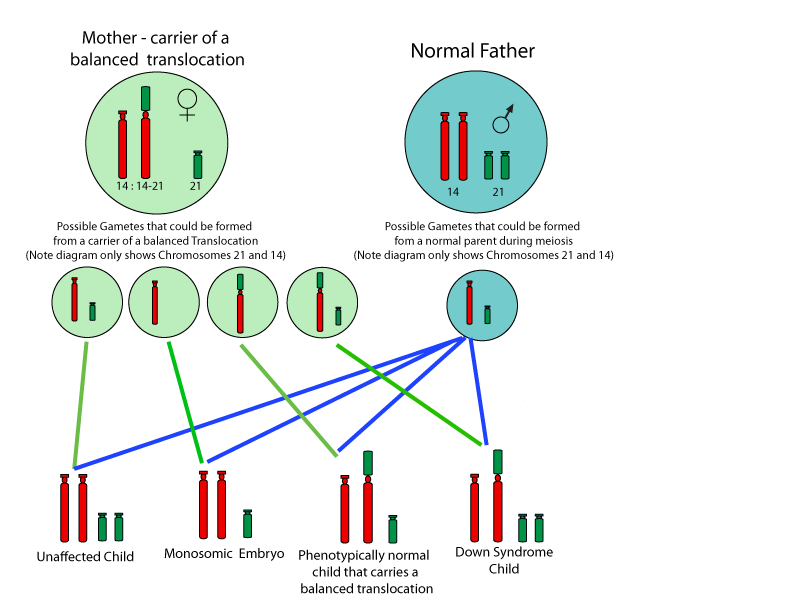

In 5% of cases, one parent is a carrier and has a ‘balanced translocation’. This means that one of the chromosomes breaks and becomes attached to another chromosome so, the person technically has a normal copy of all the genes and is completely normal. But, when their gametes are formed, the gamete that receives the translocated chromosome will end up having extra genetic material from chromosome 21. This form is thus hereditary and can recur in the family.

Segregation of gametes with a balanced translocation of chromosome 21. Image credits: http://lens.auckland.ac.nz/index.php/Aneuploidy_and_Related_Biotechnologies_Discussion_2009

There is a scientific reason behind Down’s syndrome, and it is not anyone’s fault. Those with Down’s syndrome have the same sentiments as every other human being, and it is important to understand and respect that. Awareness about the risks and prenatal tests available for chromosomal disorders is important. With scientific advancements and cutting edge research around the world, our knowledge of the dosage sensitive genes in chromosome 21 is constantly improving. we hope that, one day, there will be potential therapies that will allow us to better manage this condition.

References

- More about what DNA and chromosomes are can be found here: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/handbook/basics/dna

- More on the features of Trisomy 21: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/down-syndrome , http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/943216-overview

- An in-depth paper on gene dosage can be found here: http://www.pnas.org/content/109/37/14746.long

Thanks for finally writing about >Tale of the Tiny Chromosome | theGIST

| The Glasgow Insight into Science and Technology <Loved it!