Meditations on mindfulness: all it’s cracked up to be?

In recent years, the shortcomings of many of the pharmaceutical treatments used for mental illnesses have been nudged into the spotlight. The weaknesses have always been there, of course, but ever increasing prescriptions has led to an upturn in public interest. The fact that we don’t know precisely how anti-depressants work has made ideal circumstances for ignorance and tabloid scaremongering. Combined with more people experiencing these drugs’ seemingly scattergun efficacy, this has led many to seek an alternative to drug therapies.

Psychological therapies have always went side by side with pharmaceutical intervention as a key treatment option, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) being the most prominent in recent years. CBT focuses on changing negative thought patterns which contribute to the symptoms of depression, anxiety and other mood disorders and for some it is a very effective treatment. Brain and behaviour is a two-way street: the brain both affects and is affected by our thoughts and experiences. Thus, changing the way one thinks can alter brain activity in a broadly comparable (yet probably distinct) way to psychotropic drugs 1.

Unfortunately, it is not only drugs which suffer problems in performing on the night. Reliable evidence for CBT’s efficacy is hardly abundant and studies are often poor quality – meta-analyses of this evidence often cite a lack of good, consistent experimental design as well as low numbers of participants and studies2. There is no gold standard when treating many forms of mental illness – what works wonders for one person can leave another feeling frustrated, misinformed and, crucially, still unwell. Many patients will know the struggle of attempting one form of anti-depressant after another or seeing therapist after therapist. Finding the right drug or doctor for each patient can involve a lot of trial and error, and it is understandable that the public expect the ‘experts’ to know better.

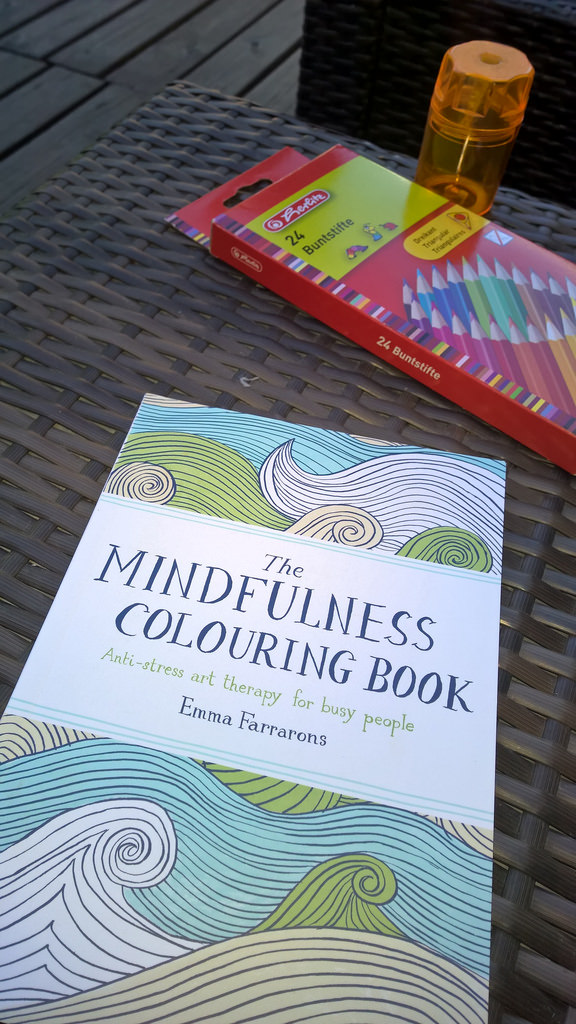

Psychological therapy does benefit from one key publicity charm – it is all natural. Perhaps due to this wholesome, brown-bread-factor, alternatives to drugs will always be fashionable. In vogue currently is mindfulness – a branch of therapy centred on focusing, encompassing meditation and awareness of the self and the present moment 3. Its popularity means that now you can pop to your local Tesco and pick up a Mindfulness Colouring Book, containing a variety of patterns to help you achieve zen-calm. Apps represent another ubiquitous option to get your daily dose, more often than not on the basis of a paid subscription.

The mindfulness colouring book, which might help those suffering from mental illness, or might just be a good excuse to do some nostalgic colouring in.

Credit: Helen Penjam via flickr (CC BY 2.0)

NHS-issue mindfulness comes in the form of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioural therapy (MBCBT), a series of sessions which focuses on the feelings involved in depression: downward spirals and oppressive thoughts which contribute to negative and destructive thought patterns. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has long endorsed MBCBT, and recent news reports have been overwhelmingly positive, including much emphasis on a publication in the Lancet suggesting that MBCBT provided similar outcomes in terms of relapse compared to long-term courses of anti-depressants 4.

But how much of the recent zeal for mindfulness is rooted in science, and how much is marketing? Studies into MBCBT have produced many positive indications over the years. One literature review concludes that mindfulness-based therapies can provide an ‘effective intervention’; another less glamorously sums it up as ‘moderately effective’ – but crucially when comparing the performance of drugs, CBT and other behavioural therapies for anxiety, stress and depression there was no difference found between the three treatments 5.

On the other hand, a major study found no significant differences between patients using MBCBT and those receiving cognitive psychological education – similar to MBCBT but lacking the mindfulness component – calling into question whether mindfulness is simply piggybacking on the general success of psychological treatment. The same study also highlights the lack of evidence for MBCBT being successful in milder forms of affective disorder 6. If mindfulness is ineffective in mild cases, is an app likely to benefit the majority of those buying it?

Overall, the evidence is mixed. Recently, the number of studies published in the field has been huge, with many positive findings (as summed up in the aforementioned review papers). The volume of positive findings is encouraging for advocates of mindfulness, but others believe some of the research has not been reliable enough 7. But it seems clear that for some forms of affective disorder, mindfulness has the potential to produce similar results as drugs. Even if the evidence is inconclusive, if it can be as effective and doesn’t involve taking nasty chemical pills, then what’s the harm?

Well firstly, there are the rarely-discussed side effects: a study of both amateur and experienced meditators found almost two thirds reported at least one adverse effect and 7% described ‘profound’ adverse effects – for example anxiety or depression 8. More recently, a neuroendocrinological study found that subjects participating in mindfulness exercises (as opposed to a cognitive training control program), reported while feeling less stressed, had higher levels of biological stress markers and cortisol as well as higher blood pressure 9. It isn’t hard to imagine how acknowledging our thoughts, rather than distracting ourselves from them, may distress some people rather than calming them.

The hype itself must also be considered – when a treatment model, no matter how effective, is taken out of professional hands, it becomes problematic. Recent mainstream coverage reflects the pedestal mindfulness sits on in some circles – it is revered as a cure-all against a backdrop of pharmaceutical mistrust. Mindfulness is now hugely marketable; big money spinners include books, apps and private sessions, sometimes offered by people without the necessary training and expertise to deliver the therapy safely. While the availability of these may benefit some, the financial motivation must be kept in mind; when money is involved, unscrupulous people often seek to exploit the vulnerable: in this case, patients desperately seeking a cure. Whilst many advocates of mindfulness act in good faith, the adverse side-effect of fostering suspicion of medicine gives opportunity to the less-well intentioned. Thus, the mindfulness bandwagon risks endangering some of the people it aims to help. In the field of mental health, misinformation is sadly both rife and potentially devastating.

Mindfulness clearly has an important place as treatment – and for those for whom the drugs don’t work for, it is important that viable alternatives are available. But presenting it as a panacea benefits no-one but the folks selling the colouring books at Tesco.

This article was specialist edited by Olivia Kirtley and copy edited by Michael Differ.

References

- For a summary of how psychotherapies affect brain functioning, see this article from the Psychiatric Times: http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/psychotherapy/how-psychotherapy-changes-brain

- Cochrane reviews provide meta-analyses of medical research. Many conclude a lack of quality evidence for CBT in treating depression, such as: http://www.cochrane.org/CD008705/DEPRESSN_third-wave-cognitive-and-behavioural-therapies-versus-treatment-as-usual-for-depression

- More general information on mindfulness can be found at http://oxfordmindfulness.org/about-mindfulness/ – an organisation with links to Oxford’s Professor Mark Williams, a key researcher in the field.

- The Lancet study, headed by Prof Williams, described both MBCBT and anti-depressants as providing ‘enduring positive outcomes in terms of relaspe’: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)62222-4/abstract

- The reviews mentioned are Piet and Hougaard, 2011: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21802618 and Khoury et al., 2013: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23796855

- This major study also involved Oxford’s Prof Williams: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24294837

- Amongst these voices are Catherine Wikholm and Miguel Farias. Wikholm wrote a Guardian article (http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/may/22/seven-myths-about-meditation) discussing meditation myths, and the pair are the authors of The Buddha Pill – a book further discussing the potential problems relating to mindfulness.

- This study was conducted in the early 1990s – recently others have called for deeper research into these adverse effects and who may be vulnerable to them: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1428622

- The authors of this study speculate that mindfulness training might ‘foster greater active coping efforts’: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24767614