Mind Games

Apps like Lumosity, Memory Trainer or Brainmetrix all promise to provide more or less the same things: scientifically designed games which lead to better memory, increased intelligence, attention span and problem solving abilities, as well as prevention of neurodegenerative illnesses. Such websites are filled with testimonies of satisfied customers and confident researchers, but the average user might have a hard time discerning between reliable scientific findings and bold advertising.

The consensus on these games and training tools is still being built. First of all, the brain is an extremely complex organ and its inner workings are yet to be entirely deciphered. The ubiquitous umbrella term of “intelligence” covers an array of functions and properties, which differ in terms of mechanism and conventional acknowledgment. Confidently advocating that a certain game increases intelligence might not be exactly true, but it can be vague enough to not qualify as a lie either. Even the concept of memory is not as straightforward as it sounds. Memory can be involuntary and fleeting or it can be focused on a specific piece of information, it can be short-term or long-term, it can be spatial, emotional or visual and it can be influenced by factors such as genetics, stress and habits established across the span of a lifetime.

Some claims of such companies are more striking and detailed than others, but all of them revolve around the same cognitive processes, mainly attention or spatial and working memory. Many of these statements are also put forward with the alleged oversight of specialists. Lumosity has even set up something called the Human Cognition Project, an ongoing collaboration with universities around the world, which is supposed to lead to better designed games and more reliable data regarding their actual effects.

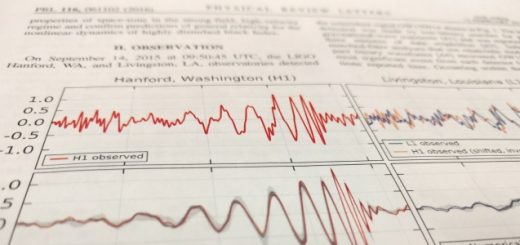

But evidence on the efficacy of these training tools is still contentious. On the Lumosity webpage we can find a list of completed and ongoing studies which demonstrate the web games’ effectiveness on various cognitive functions. One of them was carried out on breast cancer survivors, who normally suffer from cognitive problems following chemotherapy, and assessed their scores in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, a popular neuropsychological test which appraises executive function. 1 Over a period of 12 weeks prior to the test, a fraction of the subjects trained with the games commonly found on the company’s website. Afterwards, this group and a control group both sat the test. This study, which was published in the journal Clinical Breast Cancer, showed that the group which had used Lumosity games for training scored much higher than the control group. Another study involved web-based cognitive training tools in which visual attention and working memory were heavily exercised and found that individuals who played these games performed increasingly better in the following cognitive assessment. 2

Image Credit: Emilio Garcia via Flickr ( License )

Other positive studies related to brain training tend to variate on the same theme and show subjects performing better and better within specific parameters. However, there is a quite a bit of research questioning the transferability of these skills. One paper published in The Journal of Neuroscience. 3 expands on the effect of active training on inhibitory control, which is a complex of mechanisms crucial for many mental processes and ultimately for task performance. The study, which was carried out by Elliot T. Berkman and colleagues, suggests that performing the task given by a game improves the ability to perform that specific task (which is to be expected), but it can’t translate to other cognitive functions. Coincidentally or not, it is possible that in the breast cancer study the games the subjects were training with were designed to improve the exact skills that the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test was meant to assess later on.

Another problem in this field is the difficulty in designing blind studies, which is vital for unbiased results. In a blinded study, the participants are not given any information about the study being performed or the expected results, as this might influence subjects and lead them to perform differently. But these games have been quite heavily advertised and their purpose is quite obvious even if one has never laid eyes on the adverts; therefore, creating a blind study becomes quite a challenging task and the results obtained elsewhere can easily be questioned.

Despite the insufficient amount of research and the contradictory findings, many people seem to be pleased with the effects of brain fitness tools. It could be that the tasks the games employ are actually improving cognitive functions or, surprisingly, that said functions did not require improving in the first place. Perhaps one of the least advertised possible benefits of brain training is that it might supply users with a cheap, fun way to gain a significant amount of self-confidence, which can lead to better performance in-game and elsewhere.

One important issue to point out is that if these types of exercises indeed deserve recognition across some task-specific capabilities, this recognition should probably be extended to many more games which are not marketed as brain fitness. Strategy, role playing and adventure video or board games are abundant in tasks which employ problem solving abilities, attention, forward planning or cooperation with other players. Furthermore, childhood games involving numbers, colour coordination or vocabulary play a pivotal part in early development. Take a few steps back and your notion of brain training could encompass all activities that stimulate the mind, from learning to play an instrument to reading this article, and most of them don’t even require a monthly membership.

Mind Games by Teodora Aldea was copy edited by Charlie Stamenova.

References

- Shelli Kesler (2012) Cognitive Training for Improving Executive Function in Chemotherapy-Treated Breast Cancer Survivors. Clinical Breast Cancer Volume 13, Issue 4, Pages 299–306

- Joseph L. Hardy et al, Enhancing visual attention and working memory with a Web-based cognitive training program. Mensa Research Journal, Vol. 42(2)

- Elliot T. Berkman et al (2014) Training-Induced Changes in Inhibitory Control Network Activity. The Journal of Neuroscience, 1 January 2014, 34(1): 149-157; doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3564-13.2