Identity and Psychology: Part 2

Trigger warning: this article contains sensitive information regarding trauma/suicide.

If you have not yet read Identity and Psychology Part 1, find it here: https://the-gist.org/2019/06/identity-and-psychology-part-1/

The 2nd speaker at the ‘Our Society’ event was Professor Rory O’Connor from the Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow. He studied his PhD at Queen’s University in Belfast before moving to Glasgow to pursue his research career. He is a registered health psychiatrist who is broadly interested in wellbeing, particularly in the areas that lead to distress and devastating consequences, including suicide, which was the focus of his talk. Rory’s talk was engaging, fascinating, informative and provided a scientifically sound insight into some of the processes underpinning suicide.

Rory’s lab aim to identify key players driving suicidal behaviour by using epidemiology (incidence and distribtuion of disease) and research studies with people who are thinking about or have attempted suicide.

Rory started by providing statistics, which is always a great way to begin a scientific talk. We all know suicide is a huge problem, but hearing the real world statistics was frightening. 800,000 people die every year from suicide. Approximately 700 of these deaths are in Scotland. Rory highlighted that the rates are also very high in Northern Ireland, which added a personal sentiment to the talk as this is where he grew up. The statistic with the most impact shortly followed; the biggest killer of males under 50 years old is suicide.

So, many people may think about suicide and even consider it, but what factors influence people who go through with it and those who don’t?

The key is that there isn’t one explanation. Unsurprisingly, one of the biggest risk factors of suicide is suffering from a psychological disorder, most commonly depression. Rory described suicide as a ‘behaviour’ of depression which has devastating consequences. This was a concept that surfaced throughout the talk. If we consider suicide as a behaviour of depression, then it could develop in anyone suffering from depression. You would think this would convince society to focus more resources into suicide prevention? What is interesting is that only 4% of people who are treated for depression commit suicide. So it’s clear that intervention prevents the development of suicidal behaviour. Rory developed this idea by saying that for some, suicide isn’t a choice, it’s a behaviour, and ultimately a decision to end pain.

Rory went onto describe another risk factor of suicide; the ideation of suicide. Having your 1st thought of suicide makes it more likely for these thoughts to appear for a 2nd time. It seems simple, but, if you intervene early, it reduces the likelihood and frequency of these thoughts, thus reducing the risk of suicide. Rory stated that 30% of people with suicidal thoughts commit suicide, and this is the 30% that his research aims to understand.

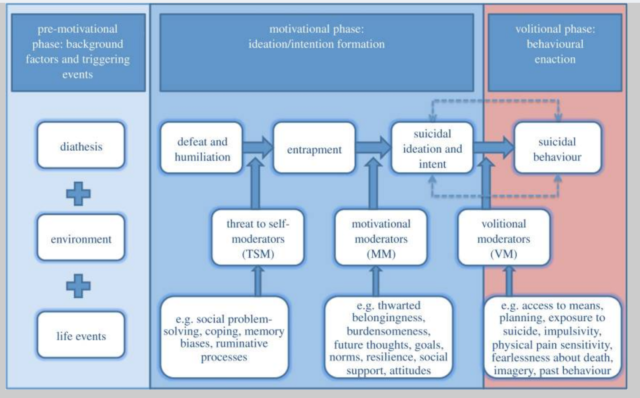

We were then introduced to the Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicide Behaviour, developed by Rory and colleagues. This model describes the steps involved in the transition from thoughts of suicide to attempt. It may sound obvious, but studying these steps and patterns of behaviours helps to develop methods of intervention and categorise risk for people at different stages of their transition from suicidal thoughts to action. The model has three phases: pre-motivational, motivational and volitional. Rory specifically highlighted social perfectionism as a common pre-motivational factor, which is particularly relevant nowadays due to social pressures. Social perfectionism usually involves an individual setting high personal standards, that are usually perceived as ideas that they think other people have of them. This feeds into the motivational phase because when a perfectionist experiences a life-changing event they feel more easily defeated, which can lead to an individual feeling ashamed, rejected and suffering from entrapment. You can see how this series of events can lead to a decline in mental well being. Rory goes on to describe 8 factors that govern the model, including impulsivity and mental imagery of death. You can read about these factors in Rory’s publication1.

To finish, Rory described his research relating to the stress hormone, cortisol, and its relationship with suicide. Cortisol is a vital hormone that we need for emotional regulation and problem solving and can be measured with a saliva sample. In his study, he had three groups of people: controls, people who have thoughts of suicide and those who have attempted suicide. First, he explained that the people who had previously attempted suicide had experienced high levels of childhood trauma (78.7%). He also found that those who had experienced high levels of childhood trauma had a blunted cortisol response when exposed to stressful stimuli (the stress test involved a cold physical stimulus and mental arithmetic to simulate a stressful situation). Ultimately, the study showed that the level of exposure to traumatic experiences during childhood can predict how much cortisol you release when you are in a stressful situation. This is fascinating and means that the stress response is highly relevant in suicide research. You can read more detail on this study here2.

Overall, Rory did an excellent job at providing insight into the mind of someone who is suicidal.

Importantly, he conveyed to the audience why it can be so hard for someone in this mindset to escape it, and therefore why research into the causes and stages underpinning suicide behaviour is so vital.

This article was edited by Sonya Frazier.