Glasgow Skeptics: “What Phrenology Teaches Us About Ourselves”

Phrenology is a largely derided 18th-century pseudoscience, which uses the shape of a person’s skull to predict aspects of their personality. It seems then to be the perfect topic for a group of sceptics to dissect, and the large turn out for Professor David Price’s talk 1 reflects an interest in doing so. Debunking trash science is a sceptic’s bread-and-butter, but acknowledging that some good could come from it might not always be as easy, particularly with a topic with as unsettling a history as phrenology.

As David puts it; “Phrenology could be told as a tale of the good, the bad, and the ugly – some good comes from it, some bad, and some very, very ugly.” If you have heard of phrenology before then you will likely be aware of the ugly side; historically, it has been used to justify deeply racist and entirely baseless viewpoints. But the good may be less familiar.

David’s talk began with a little history to the topic. We heard the humorous tale of Jacque Alexander Tardy, a failed pirate whose exploits were meticulously recorded during his trial. After his death, his skull was disinterred, and certain bumps on his skull were associated with “destructiveness”, explaining his yearning for a pirate’s life. And the reason anyone ever cared to look at this? Phrenology.

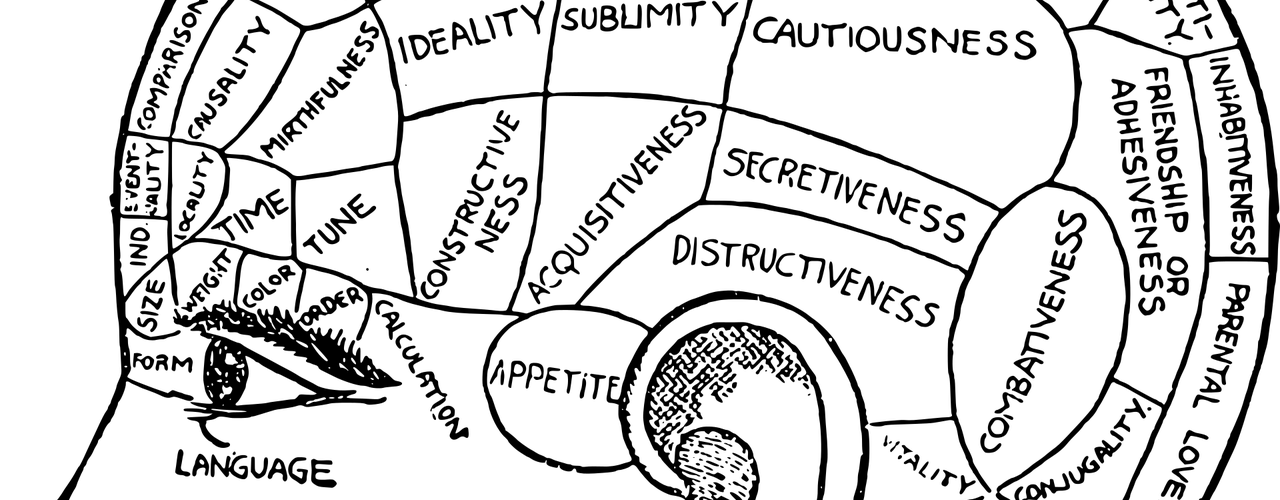

Phrenology was first proposed by Franz Joseph Gall in 1798, and he attributed five central ideas to the theory:

1. That the brain is the organ of the mind (David was quick to point out that while this may not seem ground-breaking to us, it was an unusual idea at the time);

2. The brain is split into faculties, and different regions of the brain relate to different functions;

3. The size of the organ (or brain area) is a measure of its power;

4. The shape of the brain is determined by the makeup of these areas;

5. The skull takes its shape from the brain; therefore, the shape of a person’s skull can be used to determine the size of their brain regions and, hence, their personality.

If you have ever studied neuroscience you may notice that number 2 on that list is not so far from the truth: regions of our brain do have different roles – for example, damage to the visual cortex can result in visual impairment. However, the phrenologists believed that there was much more granularity in this and that different brain regions related to specific personality traits. The bulged area of Tardy’s skull that was attributed to his “destructiveness” tends to be smooth in people of Senegalese descent and led phrenologists to make the sweeping characterisation that this entire race of people must be “mild and agreeable”. This is not only terrible science but also woefully biased. Another example of this scientific racism emerged in 1839 when Samuel Morton attempted to justify his ideas by measuring skulls of men and women of different ethnicities and compared the sizes to determine intellect. His eye-rollingly predictable conclusion was that the “white American man” was “superior”.

This then begs the question: “how could this possibly have led to any good”? Dr William Brown, a prominent Scottish psychiatrist of the 1800s, believed in phrenology, and through this, he advocated for the idea that mental illnesses had a physical basis. He pioneered the idea of moral medical treatment 2 and introduced a scheme called “art in madness”, where he encouraged art as a therapeutic outlet (art from this time can be viewed in the Crichton collections). While some of his ideas may seem parochial now, he was revolutionary by treating patients in mental care institutions with humanity.

Since then, phrenology has been widely condemned and empirically disproven. The first paper to use modern neuroimaging techniques to assess phrenological methods found that there was no value in the pseudoscience and summarised this in an incredibly brief results section, simply stating: “The phrenological analyses produced no statistically significant or meaningful effects.” 3

Given this, it may seem that there is no need to challenge phrenology, as it has already been thoroughly discredited. However, it does carry some important lessons into today’s scientific practice. While David began his talk by acknowledging the title – “What Phrenology Teaches Us About Ourselves” – and answering with “not very much”, he did impart some wisdom that we have arguably learned from it. Through studying the mistakes of phrenology and its proponents, we do learn something about the way our brain works. Phrenology is a laughably extreme example of a phenomenon that we can all be guilty of: confirmation bias.

David illustrated this by way of a “Private Eye” style spot-the-difference – where two people, armed with the same information, come to opposing conclusions. In this case, two phrenologists of the 1800s both believed that African people who had been forced into slavery in the US had a skull morphology that indicated a “docile nature”. Caldwell, an advocate of slavery, used this to argue that people of African descent required an owner, as they could not be left to their own devices; his opponent argued that this characteristic meant they should be protected from slave owners. It highlights a familiar issue – no matter the data, interpretations can be shaped to fit what we want to believe.

Confirmation bias is still an issue that scientists can fall victim to – after all, “scientists are human, just like anybody else[…] just with letters after their name and an inflated sense of their own opinion.” And regrettably, phrenology is not an idea that has completely gone away. While not covered in David’s talk, it is worth noting that a new tech company, Faception, is attempting to use machine learning methods and “face analytics” to determine a person’s personality. Worryingly, they claim that it can help to detect a “potential terrorist” or a “potential criminal” just by their face. It is easy to imagine how this could go terribly wrong and further fuel biases already present in society.

When asked if there were any areas of science that David felt were particularly at risk of confirmation bias, he spoke of the limitations of studies of humans that cannot, for various ethical reasons, have a case-and-control, as it may not be possible to introduce an intervention.

A take-home message, then, that is particularly on-brand for the event: be sceptical and, if you’re a scientist, be open to the idea that your hypothesis might just be wrong.

This article was copy-edited by Beth Waddington.

I was trying to find a person who would be in a position to clearly browse

me about this matter and was fortunate enough to find you.

Thanks a lot for the detailed reason, you drew attention to a very common issue!

Although I share your opinion for the most part,

I believe that a few things are worth using a more detailed appearance to understand what is

going on.

“And regrettably, phrenology is not an idea that has completely gone away. ”

” just with letters after their name and an inflated sense of their own opinion.”

you mean like a PHD student ? well ok .