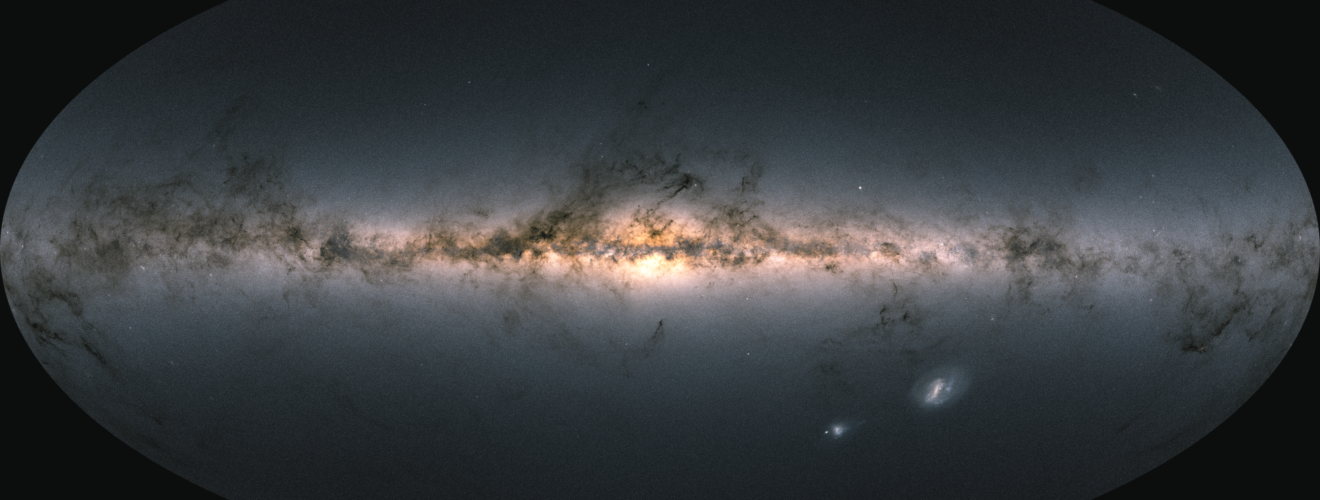

Gaia: A decade in space, mapping the Milky Way and more

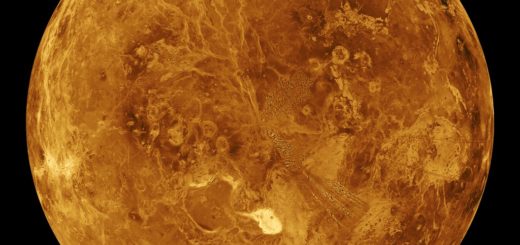

Our Milky Way galaxy is home to 100 billion stars, with some estimates reaching as high as 400 billion[1]. By observing these stars with the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gaia space observatory, astronomers are expanding our understanding of our galaxy’s formation and evolution. Gaia was launched on 19th December 2013 for a five-year mission which has been extended to 2025[2]. Gaia’s primary aim is to produce the most precise and complete three-dimensional map of the Milky Way.

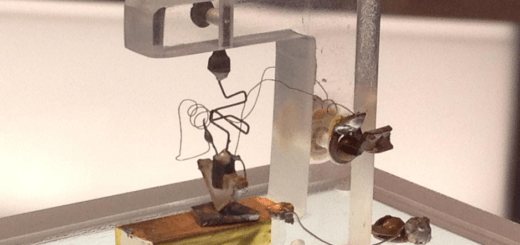

Gaia contains two identical optical telescopes which direct the light it observes to its three instruments[3]. The astrometric instrument is used to determine a star’s position in the sky, its distance from Gaia and its speed as it moves across the sky. The spectrometer measures how fast objects are moving away from or towards Gaia (their radial velocity). Lastly, the brightness and colour of a star are measured using the photometric instrument. From this, an object’s change in brightness and its temperature, mass, chemical composition and age can be determined.

Gaia’s observations began in 2014 and have since delivered a plethora of data through five data releases; the latest being in October 2023[4]. Gaia has mapped nearly two billion celestial objects, including over 1.8 billion Milky Way stars, positions for 156,823 asteroids in our solar system and more

Gaia’s data can inform us about our galaxy’s past and future. In 2018, a team of astronomers led by Professor Amina Helmi of the University of Groningen studied a sample of seven million stars catalogued by Gaia and found that a subset of 30,000 were moving in the opposite direction[5] [6]. These findings were consistent with computer simulations of how stars would behave after two large galaxies merge, and so they concluded that the Milky Way merged with a large galaxy around 10 billion years ago.

When Gaia surveys the sky it also finds objects outside our galaxy. One such example was the data release of potential quasar candidates. Quasars are the luminous centres of distant galaxies where supermassive black holes are consuming the surrounding gas[7]. Studying distant quasars can give us clues about the evolution of the early universe.

The next data release is not anticipated before the end of 2025, with the final legacy data release not before the end of 2030. Therefore, Gaia will continue to shape our knowledge of the Milky Way and beyond for years to come.

[1] https://www.sciencefocus.com/space/how-many-stars-are-in-the-milky-way

[2] https://sci.esa.int/web/gaia/-/47354-fact-sheet

[3] https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Gaia/Science_instruments

[4] https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Gaia/

[5] https://www.rug.nl/news/2018/10/astronomers-discover-the-giant-that-shaped-the-early-days-of-our-milky-way

[6] https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Gaia/Five_fascinating_Gaia_revelations_about_the_Milky_Way

[7] https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-resources/what-is-a-quasar/

Edited by Hazel Imrie

Copy-edited by Rachel Shannon