COVID-19 vaccines, safe or rushed?

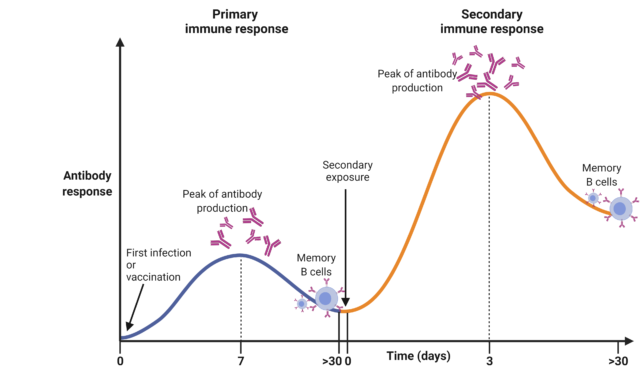

To understand why vaccines are necessary, we first need a very basic understanding of the immune response. When a person is ill, for example, because they have been infected with a virus, the immune response develops in two stages. The first stage is called the innate immune response, which is composed of a group of cells that try to contain infection as soon as it occurs. We can call them the “foot soldiers”. The second phase of the immune response, the adaptive phase, takes longer to occur and it is composed of the T and B cells, and the antibodies. We can call them the “cavalry”, and they are more effective when killing the virus. So, the vaccines use a harmless form of the “enemy”, which in this case would be the virus, to activate the immune system and “train your cavalry” against it. Therefore, vaccination allows the adaptive immune system to be prepared and respond much faster than when a person is infected for the first time.1

(Diagram created by Author using BioRender, 2021)

Currently, there are three vaccines that have been approved against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic and the current situation we are living in. The fact that there are multiple vaccines is highly beneficial. One of them might be more effective in a population group, for example, the elderly, than the others, as the immune system from different age groups differ. In addition, they address the problem of manufacturing doses due to the high demand.

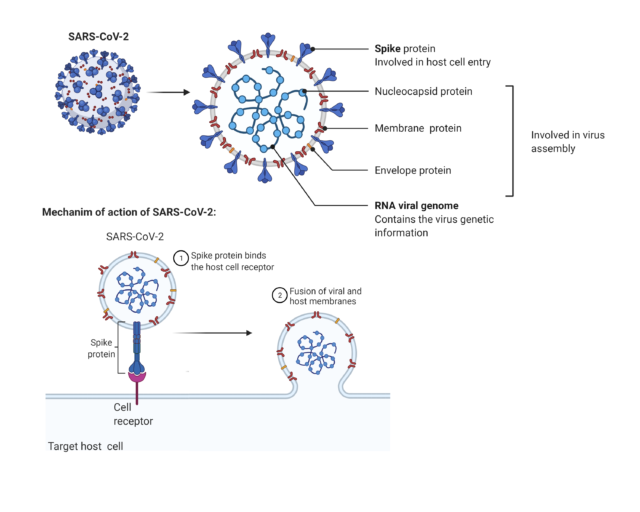

A classic approach to vaccination uses the full virus, which is dead or attenuated. This may present some health risks due to possible reactivation of the virus, or may not elicit an immune response big enough. Now we have more sophisticated and innovative vaccines, which deliver the information necessary to make the spike protein to our cells, either via a harmless modified viral vector (AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine) or a transcript (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccine). This means none of the vaccines can cause COVID-19, since they do not have the virus.

(Diagram created by Author using BioRender, 2021)

The viruses take advantage of the infected person’s cells to produce the different molecules that make them up using a transcript (RNA) with their genetic information. Amongst the several proteins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, its spike protein is the key that allows the virus to infect our cells. So antibodies targeting this protein may protect us by stopping the virus from entering the cells. The vaccine delivers the genetic information for the spike protein only to our cells, which will produce the protein, our immune system will recognise it and react to it2. This will lead to the production of antibodies able to recognize the actual virus and stop it by binding its spike protein.

A big concern of the population understandably has been related to the safety of these vaccines3. So, aside from the fact that these cannot infect you with the virus, it is important to know that:

- The vaccines have gone through extensive clinical trials and have been assessed by organizations independent from the pharmaceutical company. However, it is important to take into account no medicine is risk-free. Even the paracetamol prospect has a long list of side effects. Nevertheless, these organizations have ensured that the vaccine is safe, and the benefits greatly outweigh the risks.

- Aside from the information to train our immune system against the virus, the vaccines are mostly made with water; preservatives and stabilisers to maintain the quality of the vaccine and prevent contamination, which are often naturally found in the body or food at much higher levels. They most definitely do not contain any 5G to spy on all your web searches.

- The vaccines have not been rushed, and they have followed all the procedures necessary. Usual delays are due to funding, ethical approval, volunteer recruitment or production. However, the emergency situation due to COVID-19 has trumped all bureaucracy; international doctors and scientists have collaborated and worked hard to develop the vaccine; governments and funding bodies provided great financial resources; volunteer numbers were very high, which allowed for exhaustive clinical trials; and manufacture was run as the same time as the clinical trials to speed up the process. Moreover, there are other examples of vaccines produced under a year, like the seasonal flu vaccines.

- The viral vector used in the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine is a virus that has been weakened and manipulated to not be able to replicate.

- The use of mRNA vaccines builds on the knowledge of their use for other diseases since their use in cancer showed good preliminary results4. In addition, the mRNA vaccine is in clinical trials as a vaccine against other viruses, like the Zika virus5. While viral vector vaccines have been used for other diseases, such as Ebola.

The mRNA from the vaccine will be degraded naturally within hours, as it is a highly delicate molecule. Moreover, it cannot alter a person’s DNA, since it cannot enter the cell nucleus where the genetic material is located.

The vaccines show high effectiveness, especially the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, and they have been shown to protect efficiently from severe COVID-19 disease. It is worth noting vaccines do not have to be 100% effective. For example, the Salk polio vaccine was 70% effective against type 1 poliovirus6.

Two doses are needed in each of the different vaccines, in order to provide long-lasting protection. The only side effects that have been reported – soreness, swelling at the site of infection, tiredness or a slight fever – are non-lasting and indicate that the immune system has been activated. Hence, the vaccine is completely safe7.

Although vaccination is extremely effective for the majority of the population, there is a possibility to have COVID-19 after being vaccinated, due to the variation in the immune system of each individual. In addition, some people might get infected before the vaccine has had a chance to act since the immune system can take up to 14 days after vaccination to develop immunity against the virus. Currently, it is not yet known how long immunity to COVID-19 from the vaccines will last. So far, the results from the clinical trials indicate ongoing protection8.

Usually, the vaccines are not only beneficial to us but by vaccinating ourselves we are protecting others, through a concept called “herd immunity”. This protects individuals who can’t vaccinate, such as young children or people whose immune system is weakened like individuals with cancers undergoing chemotherapy. So, if few people are vaccinated, the virus can infect many individuals and spread very fast. If a high number of people are vaccinated the number of people who can be infected is very small, thus reducing the virus spread. At the moment, it is not clear whether vaccinated individuals can infect other people. Therefore, it is crucial that you wear a mask, follow the social distancing measures and wash your hands regularly to prevent the spread.

It is key that we all vaccinate when we have our opportunity. Even if you have had the COVID-19, scientists are recommending that you vaccinate. Firstly, because there have been cases of reinfection. Secondly, because it is currently unknown how long immunity will last, and the vaccines are likely to provide immunity equally or longer than normal infection. If you already have some immunity, the vaccines can boost your immune response to make it more effective9.

Regarding the new variants, it is not yet known the efficacy of the vaccines to them. However, it is likely that they will provide some level of immunity or that they will have to be slightly modified to provide better specificity to that particular strain. Hence for the moment, the vaccines are our best opportunity against the infection. Currently, they are a personal protection, but only if used by a large part of the population. Vaccines can relieve pressure on the health system and lead us back to our normal lives.

For more information on the vaccine process, the author recommends that you check out “How to make a vaccine in record time” from the University of Oxford10

This article was specialist edited by Giuditta De Lorenzo and copy-edited by Domante Rabasauskaite

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279396/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41401-020-0485-4

- https://www.immunology.org/sites/default/files/BSI%20resource_A%20guide%20to%20vaccinations%20for%20COVID19.pdf

- https://www.cancerhealth.com/article/covid19-vaccines-mrna-technology-one-day-help-treat-cancer

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04064905

- https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/blog/60-years-polio-vaccines

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/expect/after.html

- https://www.immunology.org/news/immunity-and-covid-19-what-do-we-know-so-far?fbclid=IwAR1QWa0XyIxBausfdiCqF-ygL5CR9jUSIXiJ7LwqXsUm0mZMLMB1Lr05OYA

- https://www.immunology.org/sites/default/files/BSI%20resource_A%20guide%20to%20vaccinations%20for%20COVID19.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ddDiyIKUP0M