Wait and See: A New Approach for Making a Champion

The concept of genetic favouritism or ‘innate talent’ is often the basis for talent identification programmes, and these programmes can be quite successful. It was thorough testing at young ages (and organised doping) that allowed Eastern Europeans to be such powerhouses during the Cold War. In fact 80% of Bulgarian medalists in the 1976 Olympic Games were the result of thorough talent identification processes 1. Similar models are now implemented in the UK, where thousands of youths are churned through football academies with the hope of producing a champion and, as any Scottish football fan would know, it hasn’t yielded the best results. However, what if academies are forcing youths to specialise too early? What if we waited until later in life before specialising our athletes?

Over £60 million is spent on youth football (8–18 year olds) per year, and of the 10,000 plus boys that enter these academies, less than 1% become elites. On top of that, there is psychological pressure on the young players. A quarter of 13–16 year olds in soccer academies experience complete psychologically-defined burnout 2. This suggests that turning up the pressure and seeing who makes it out of the programme may be the completely wrong approach. There is also a physiological argument to be made against such tough methods. Humans have a combination of fast twitch and slow twitch muscle fibres. Fast twitch muscle fibres allow any athlete to be fast and generate more power, whilst slow twitch fibres are better suited for endurance. The catch being that fast twitch fibres are more prone to injury 3. So by turning up the pressure, football academies could be injuring their fastest players, taking them out of the equation. Thus, we could end up with a situation where less favourable athletes with more slow twitch fibres are making it through these programmes. Clearly an alternative approach needs to be considered.

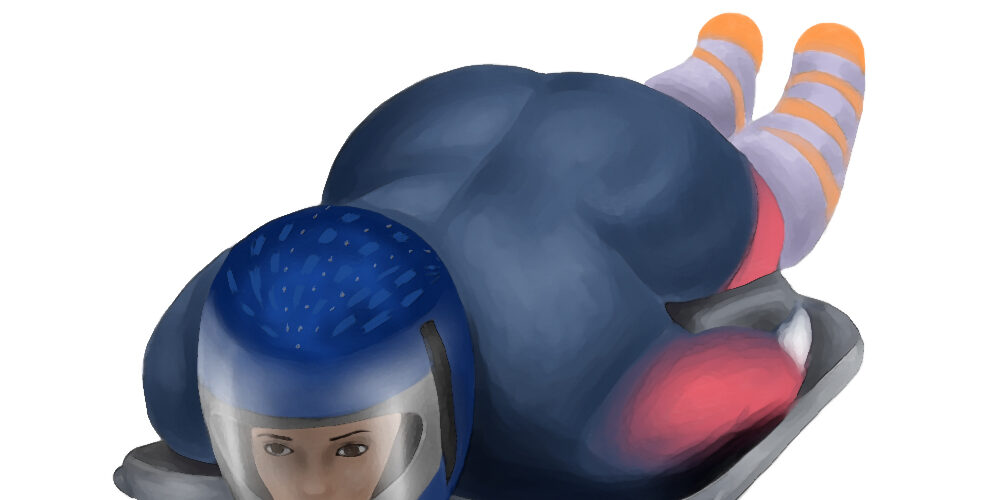

In the early 2000s, the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) set the goal of creating an elite Winter Olympic athlete in just 14 months. A very noble goal, considering that Australia is pretty devoid of ice and snow. Nonetheless, the AIS produced a female skeleton athlete, Michelle Steele, who finished thirteenth at the 2006 Turin Winter Olympics. Beyond dry-land training, her preparation consisted of just 300 start simulations and around 220 training/competition runs; while 58% of the skeleton training was completed in simulation format, 42% was full top to bottom completion/training runs. The AIS model for talent identification was simple: athletes completed a 30 metre sprint at a designated testing centre, and filled out forms detailing their personal interests and training histories. Those with the fastest times and a background in a similar sport won a spot on the team 4. Steele previously placed fourth at the Australian Surf Lifesaving Championships in 2004; a sport that also involves running really fast and throwing oneself onto a board. Lizzy Yarnold, a British skeleton athlete, hails from a similar background. Yarnold was originally a heptathlete, and was recruited by UK Sport’s Girls4Gold programme at age 20 before taking gold in skeleton at the 2014 Sochi Games. Yarnold and Steele are not alone in getting a late start. A retrospective study of Australian senior national athletes showed that 28% reached their elite status within four years of starting the sport for the very first time at the mean age of 17 years old 5, and had participated on average in at least three sports prior.

Bad Day on the Pitch (Original Artwork Illustrated by Natalia Novakovic, Commissioned by Christian C Nyberg)

This late-start model might be more viable for a sporting organisation; it avoids all those pesky adolescent issues with mental and physical maturity, enables athletes to attain elite status faster and allows the organisation to make a return on the prior investment in these athletes from other sports. The Great Medalist Study 6 conducted by UK Sport supports such a conclusion. Those identified as super-elites, i.e. world championship winners and/or Olympic medalists, specialised in their sport on average just before their 20th birthday, compared to non-medalist elites who specialised earlier at the mean age of 17 and a half years old. In addition, super-elites spent just under 1,000 more hours than elites doing another sport alongside their main sport. This correlates with another UK study 7 that found that individuals who competed in three sports at the ages of 11, 13 and 15 were more likely to compete at a national level later in life than those that had participated in only one.

By forcing children to play just one sport, organisations could be missing out on the physiological and psychological advantages of playing multiple sports. By following the strict single sport guidelines put in place by football academies, organisations run the risk of pushing out players like Leicester City’s Jamie Vardy, who was dropped by an academy at 16 for being too small, while looking for the next Lionel Messi. The fact is that the data shows that elites not only specialise later in life, but also participated in more sports prior to their main sport. It raises the question: why are academies pigeonholing athletes and trying to predict whether a young teenager will be the next Ronaldo at an age when that athlete has not matured both physically and mentally? Clearly, this single-minded approach has not worked, and organisations like football academies should consider taking inspiration from other sports and trying a different approach.

This article was specialist edited by Kristina Zilieva and copy edited by Rebecca Laidlaw

References

- The paper investigating current and previous talent identifcation programes can be found here: http://researchrepository.napier.ac.uk/2493/

- The study looking into junior football players and burnout can be found here http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/74965/2/Hill%20(2013)%20JSEP.pdf

- A study into muscle injuries and fiber types can be found here: http://www.brighamandwomens.org/research/labs/traumaresearch/MoorePublications/Chan%20Reperfusion%202004.pdf

- The scientific paper that investigaes the AIS talent program can be found here: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02640410802549751#.V4I4tJOLTBI

- A further look into the study regarding previous sports and particpation can be found here: http://cev.org.br/biblioteca/factors-affecting-the-rate-of-athlete-development-from-novice-to-senior-elite-how-applicable-is-the-10-year-rule/

- A published report of the The Great British Medalist Study: A Summary (2016) can be found with the UK Sport and the English Institute of Sport, (2016)

- The articles discussing previous sports participation during adolescence can be found here: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02640414.2012.721560#.V4JKW5OLTBI