Mothers are doin’ it for themselves: when males are optional in animal reproduction

One mystery has plagued gardeners since ancient times: how can a plant be healthy and bug-free one day, then coated in armies of aphids the next? The plot thickens — all the aphids are sisters of each other.

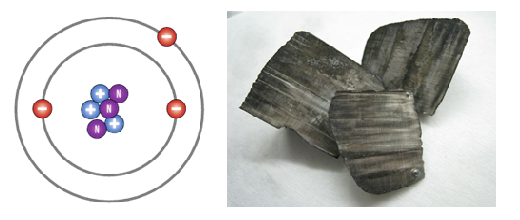

The answer lies in the mysterious and surprising phenomenon of parthenogenesis, the production of offspring from unfertilised eggs.

Aphid parthenogenesis is facultative: that is, they can reproduce both sexually and asexually, with or without male fertilisation. Other species known to use facultative parthenogenesis include water fleas (genus Daphnia), some pitviper species, and several shark species. In fact, quite a few animals have been found to dabble in a little casual parthenogenesis[1].

And who could blame them? Parthenogenesis can be a great strategy for filling up the world with your progeny. Is your species scattered thinly over a wide area, making mates hard to find? Try parthenogenesis. Need to boost your population quickly to make the most of a resource? Try parthenogenesis. In most cases, reproducing with no male input results in female offspring, a parthenote, which can also reproduce parthenogenetically, rapidly growing the population while sexually-reproducing species are still eyeing each other up and doing silly dances.

Given the opportunities parthenogenesis presents, it’s no surprise that some animals take it to extremes. Brahminy blind snakes only reproduce through parthenogenesis — there are no male Brahminy blind snakes[2]. Obligate parthenogenesis, where a species only reproduces parthenogenetically, is rare in the animal kingdom, and most commonly found in invertebrates[3].

However, for all the popularity and usefulness of parthenogenesis, it has an important drawback. A population of parthenotes lacks genetic diversity due to only inheriting their mothers’ DNA. Parthenotes will share similar strengths and weaknesses, including disease resistance, and will not be able to adapt to environmental changes as quickly as a sexually-produced population. Although parthenogenesis can help protect endangered species, the predisposition of parthenotes to the same diseases as their mothers make them more susceptible to extinction compared to sexually-produced offspring.

While parthenogenesis can be an effective get-rich-quick scheme for quite a few species, most animal species rely on sexual reproduction to produce genetically variable offspring. Males have their uses, after all.

[1] https://academic.oup.com/biolinnean/article/112/3/461/2415863

[2] https://www.jstor.org/stable/3891816

[3] https://academic.oup.com/evlett/article-abstract/1/6/304/6697453

Edited by Despoina Allagioti

Copy-edited by Rachel Shannon