Damn, spider. Why you so hairy?

They may put Little Miss Muffet off her curds and whey – but a spider’s hairs are crucial to its survival.

Many people suffer from arachnophobia, a treatable phobia of spiders. But what is scary about small, harmless animals? For many people, it is the extreme fuzziness of spiders that imbues such fear. Spider fuzz is not only there to scare humans, however; spiders have many different types of hair covering their bodies, for all sorts of reasons from self-defence to combing silk.

Most hairs on a spider are organs, complete with a nerve supply and muscles at the base so that they can be moved. The sockets from which spider hairs grow are different shapes, allowing movement in different planes. There are so many different hair types that I cannot fit them all into one article, but the following are my favourites.

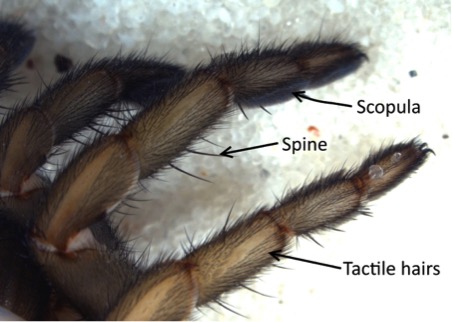

Tactile hairs

Touching one of a spider’s many tactile hairs causes it to bend, and to move in its socket. The socket is quite tight around the base of the hair, allowing only limited movement; however, since the hair also bends when touched, the spider receives plenty of information about the whereabouts, and velocity, of the stimulus 1.

Spines

Spines are modified leg hairs that are switched on and off by the spider’s haemolymph (blood) pressure. When the haemolymph pressure in a leg increases, the spines stand erect and become sensitive to impulses from their three nerves. When haemolymph pressure returns to normal, the spines flatten and are no longer sensitive. In addition to their sensory roles, leg spines can fulfil other tasks; for example, backwards-facing foreleg spines prevent captured prey from escaping. On the hind legs of some spiders, spines form a comb which is the ideal shape for manipulating silk 2.

Brushes

Jumping spiders have massive, complex eyes used in hunting, spotting potential mates, and appearing cute on internet memes. Those eyes have no lids, so the jumpers (and some other spiders) have to clean them using specialised brush-like hairs on their pedipalps.

Scales

Some spiders have dazzling colours caused by light reflecting from flattened, almond-shaped hairs called scales. Different patterns of ridges on the scales diffract light, causing the green, black and white patterns on male Cosmophasis umbratica and many other spiders. Jumping spider scales, in particular, reflect ultraviolet light in males. If a male C. umbratica can’t see any UV scales on another male (or his mirror image), he courts the other spider as though it were a female. Similarly, female C. umbratica ignore males whose scales aren’t reflecting UV light 3.

Urticating hairs

If you startle a New World tarantula, she will turn her back to you and rub it vigorously with her legs. The display looks quite cute, until you realise that she has dislodged a cloud of invisible, barbed hairs that stick in your skin and itch like crazy. The hairs can inflame sensitive areas such as the eyes and lungs, making a potential predator extremely sorry that it picked a tarantula as its meal. There are four types of urticating hair; all are pointed and barbed 4.

Scopulae

You may have noticed that, while some spiders fall into the bath and cannot escape, others happily walk upside-down on the ceiling. The difference between ninja-spider and pathetic bath-lurker lies in my favourite hairs of all: the scopulae. Look at the bottom of a tarantula’s foot, and you will see an array of hairs so dense that the spider appears to be wearing slippers. Each scopula hair has many, even tinier, hairs sticking out of it, each of which makes contact with the surface over which the spider is walking. These thousands of contact points take advantage of van der Waals forces: weak physical forces that, together, are extremely strong. The same forces are used by gecko feet to stick to walls 5.

A spider’s hairs are the tools of her trade. They provide her with the ability to hunt, mate, and eat. They are also essential to her function as a living bug zapper. So the next time you feel disgusted at the sight of such bizarre fluffiness, take a moment to ponder the sensitive, hairy world of spiders.

References

- Albert, J., Friedrich, O., Dechant, H.-E., & Barth, F. (2001). Arthropod touch reception: spider hair sensilla as rapid touch detectors. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 187(4), 303–312. doi:10.1007/s003590100202

- Foelix, R. F. (2010). Biology of Spiders (Third.). New York, Oxford: OUP USA/Georg Thieme Verlag.

- Hill, D. E. (1979). The scales of salticid spiders. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 65(3), 193–218. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1979.tb01091.x

- Cooke, J. A., Roth, V. D., & Miller, F. H. (1972). The urticating hairs of theraphosid spiders. American Museum novitates; no. 2498.

- Niederegger, S., & Gorb, S. (2006). Friction and adhesion in the tarsal and metatarsal scopulae of spiders. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 192(11), 1223–1232. doi:10.1007/s00359-006-0157-y