Competition has always been a major aspect of academia. We compete to achieve a place in the university and course of our choice; then we compete to get the highest grades in Undergrad or Masters so that we can apply for PhD scholarships. Throughout postgraduate degrees, we compete against the clock to get our research done, while also continuing to gain other skills, such as teaching experience or writing for award-winning student magazines. After that, we compete for post-doctoral research posts, fellowships, grant-funding, and eventually, permanent academic positions. It’s a constant battle.

That’s not to say that academia is entirely exempt from collaborative experiences. From tutorial groups and the dreaded ‘group projects’ we come to know and loathe in undergrad, through to working as part of research groups collaborating on papers, all the way through to massive international studies with multiple research groups working together. But competition can overshadow this. Unfortunately, deciding who claims first author on a paper is not always as straightforward as “whoever spent the most time working on it”, with overbearing Principal Investigators stepping in. Even in research groups with the healthiest working environments, external competition can lead to cut corners, rushed analyses, and inappropriate levels of replication; all to get research findings out first.

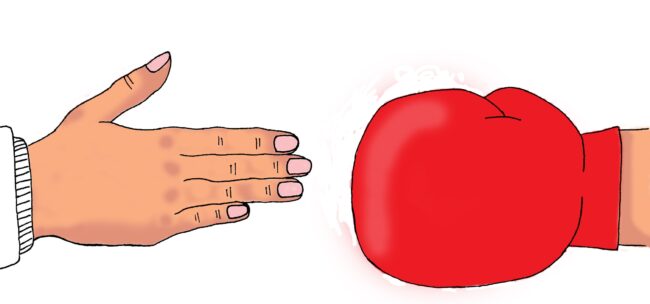

If the aim of research is to further our collective knowledge, is it time we took a step back from competitive academia and worked toward a more collaborative scientific community? Or is a little competitive spice exactly what’s needed to motivate people toward ground-breaking, Nobel-prize worthy research?

Competitive Academia

Certainly, some competition can be healthy – and I say that as a dangerously competitive person, known best in my family for crying at snakes and ladders and being ‘slightly-too-into’ pub quizzes for it to be fun for my teammates. Competing to have your work published in the best journals means that you need to complete it to the highest possible standards, so it holds up to scrutiny. A competition based system should lead to grants being awarded to the best people for the job; research groups with a proven track record of quality research in a given field. Competition can also help to prevent confirmation bias1, as multiple research teams with different vested interests work on similar research, rather than one team working to disprove a hypothesis in line with their expectations.

However, if this were a perfect system, we would never end up with questionable research making it out into the public domain. The competition to beat other research teams and publish findings quickly could mean that dodgy analyses are rushed to publication, as described in an anonymous piece written for The Guardian, which may not be unfamiliar to many academics2.

Competition can often ignore important aspects of scientific discourse. The lack of prestige associated with replication studies or for studies with negative results may mean that they are not picked up by the big journals. Negative results are extremely important in clinical settings; identifying a drug, vaccine, or diagnostic test that is not cost-effective is vital for health boards to make decisions on spending. Additionally, negative findings are important in identifying methods which fail in a particular context: for example, in anti-psychotic research, several groups identified that a commonly used mouse model was ineffective when testing for alterations to depression. Had this been published sooner, it could have saved time and money for those repeated attempts that used the same failed model3. If we do not publish negative results, it could lead to publication bias and a loss of important information in a given research field4, or, more worryingly, it may lead researchers to tweak statistical analysis continuously until they identify a result that is more exciting. To avoid this damage, publishing such information should be recognised for its value to the scientific conversation. Introducing grants for carrying out replication experiments and prizes to reward good quality research that results in negative findings can help generate this much-needed interest.

Pushing for the most prestigious awards and for publication in the most well-renowned journals can also lead to undue pressure for researchers. There is, as ever, a dark side to competition. Academia is notorious for overwork, long hours, and high levels of stress; with some reports citing that full professors work an average of 45% longer than their contracted hours, an estimated 55 hour work week5. Problematically, many academics still encourage this extreme sort of work ethic.

Collaborative Academia

Nevertheless, academic research isn’t just about competition. Collaboration is alive and kicking, and it is ever expanding – particularly in the fields of biotechnology, where cross-talk between biologists with engineers can lead to new innovations, and in computing and data sciences, where researchers (and non-academics) share coding methods via platforms such as GitHub.

International collaborations have been hailed as producing some of the highest quality research, based on the citation factor that papers receive6. Some researchers have even made calls for the Nobel Prize to be altered so that teams of researchers can be recognised, rather than the current cap of three scientists, to reflect the changing, collaborative environment in which research now operates78. But it’s important to be aware that part of the success of collaboration lies in grant funding from international research councils, and, as the UK hurtles toward Brexit, it is more pertinent than ever to ensure that these opportunities are not lost.

International collaboration is particularly important in the field of Virology; without it, efforts to eradicate smallpox would not have been successful, and eradication of polio would not be within reach as it is now. Equally, collaboration does not always need to exist purely within academia. Vaccine programs include everyone from The World Health Organisation, the health boards within different countries, Non-Governmental Organisations, and the researchers developing interventions and monitoring their success, right down to the individuals who consent to be vaccinated. Complex conditions, such as rabies, require collaboration across sectors, such as agriculture, veterinary health, as well as medicine, in order to prevent transmission between the animals which spread the disease to humans.

Collaboration has always been embedded in academia. We learn from our supervisors, lab-mates, post-docs, peer-reviewers, teaching staff, and administrative staff. Without support, we could never make it through the academic minefield. Personally, the part of my thesis I’m most looking forward to writing will be the acknowledgements section, because there is zero chance I’d still be sitting in this office, writing this, if it weren’t for dozens of others helping me at various stages.

Competition vs Collaboration

Undoubtedly, the research community has much to gain from collaboration; but the view that “competition = bad; collaboration = good” is too simplistic. There can be positive forms of competition, such as Three Minute Thesis, where people explain their entire PhD in an engaging way, with just one powerpoint-slide and three minutes. It helps to push researchers out of their comfort zone and develop new skills, as well as disseminating scientific research to a wider audience. And there can be collaborative forms of competitions (it sounds like an oxymoron but bear with me): hackathons, popular within the tech community, are events where teams are pitted against each other to solve a particular puzzle, and it can generate some hugely innovative ideas. Glasgow City Council recently hosted hackathons to solve issues in public safety, energy, health, and transport9. These events often involve people from local councils, tech companies, universities, and businesses with a vested interest in the subject matter. The pooling of funds and resources to set up an intensive competition can bring together people from different sectors to generate ideas, leading to future collaborations that may never have come about serendipitously.

It is easy to feel jaded with academia from time to time; the publication process, constant competition for grants, and red-tape can all be intimidating. And it’s true that we owe it to our funders – and by extension, taxpayers – to ensure that research is carried out in an efficient way. Competition is an important part of that – it gives us something to strive toward – but competing for the sake of accolades and glory can distract from the joint endeavours of scientific discovery and can be detrimental to research. Publication of negative results, sharing of methodologies, and large international projects can all help to shape the new, collaborative face of research. But as a naturally competitive person, I advocate that we hold on to some of the healthy aspects of competition as we move into our new, collaborative utopia.

This article was specialist edited by Mollie Wilson and copy-edited by Emily May Armstrong.

References

- https://iai.asm.org/content/83/4/1229

- https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/2018/jun/15/is-competition-driving-innovation-or-damaging-scientific-research

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3917235/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-017-07325-2

- https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/if-you-love-research-academia-may-not-be-you

- https://www.timeshighereducation.com/opinion/collaboration-and-competition-essential-research

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/sep/30/nobel-prize-fails-modern-science

- https://www.nature.com/articles/497557a

- http://futurecity.glasgow.gov.uk/hacking-the-future/