Why Are Plastics Not Biodegradable?

Biodegradable substances can be broken down by microorganisms at a molecular level. Since the chemical bonds found in non-biodegradable plastics don’t occur in nature, microorganisms are unable to break them down1. As they don’t biodegrade, they continually break down into smaller pieces through a process called elemental exposure. The average time for plastics to break down via elemental exposure is around 450 years2, and this is why plastic waste is a problem. Once they break down into to pieces smaller than 5 mm they are known as ‘microplastics’.

Where Do They Come From?

Microplastics come from two sources: the breakdown of plastic waste and industrially manufactured microbeads. Plastics in the marine environment are exposed to UV radiation, cycles of wetting and drying and microorganisms. Prolonged exposure to these physical, chemical and biological processes cause the plastics to become brittle. The weakened plastic will produce microplastic sized chips and flakes as the weather bends and flexes it.

Industrially-produced microbeads, used in many cosmetic products, pose as big a problem as microplastics made via environmental breakdown. Microbeads, being a cheaper alternative, have replaced many of the natural abrasives such as salts, bamboo, and nut shells. Microbeads are smoother, less effective exfoliators, which have been claimed to be used to sell more products. Cosmetic microbeads are washed down the drain and into the open water, as the filters in water treatment facilities have proven incapable of catching them3. Once in open water, their effect on the environment is not limited to ruining the aesthetics of beaches and sea views. The danger lies in their ability to accumulate harmful and toxic chemicals, known as persistent organic pollutants (POPs).

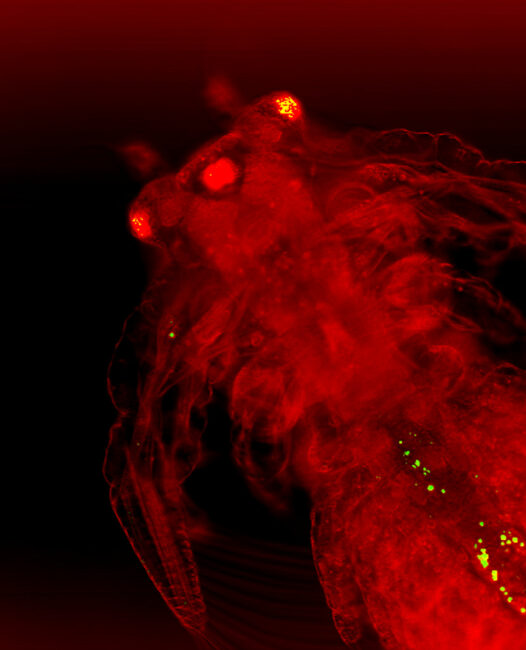

Image credit: The Plastic Oceans Foundation (CC BY-NC 2.0 License)

What Are POPs & Why Are They A Problem?

POP is a collective term for chemicals (characterised by their resistance to photolytic, biological and chemical degradation) that make it into the environment4. POPs primarily come from the runoff of pesticides, industrial chemicals and their by-products5. As POPs resist degradation, they can accumulate in the oceans and are attracted to the surfaces of microplastics6.

On the surface this may not seem like a problem but studies have shown that corals, zooplankton and crustaceans789 are unable to distinguish between actual food and microplastics. Since these animals are part of the global food web, microplastics, and the POPs on their surface, can accumulate in large concentrations in fish, blocking their gills and digestive tract and allowing POPs to accumulate in their fatty tissues10.

Drawing illustrating how the cycle of microplastics, in the environment. Image credit: Fraunhofer Institute for Environmental, Safety, and Energy Technology UMSICHT (CC BY-NC 2.0 License)

What Is Being Done About It?

Around 63% of plastic waste comes from packaging. Other sources of plastic waste such as automotive, construction and agricultural industries, as well as households contribute to the problem, but their input is small in comparison to the problem of plastic packaging11. Despite packaging being the biggest contributor to the amount of plastic waste, it has been cosmetic microbeads that have received recent attention. There has been great pressure from environmental charities and lobbyists urging government and industry to ban the use of microbeads in cosmetics.

The good news is that these actions are paying off. Although no government has placed an outright ban on using microbeads, Canada is moving towards it (having reviewed over 130 scientific papers) and a consensus from both parties that legislation is required12. The Australian government have already taken strong action and banned the supply of lightweight plastic bags with the states of New South Wales and South Australia, having agreed to phase out microbeads13. In Europe it was the Dutch Minister of Environment, Jacqueline Cramer, who set the ball rolling, calling for the European Union to ban microbeads. Following this, earlier this year, the European Commission launched a study to determine whether EU regulation is needed14. Furthermore, as of March this year, the UK government has published a report assessing the impact of microplastics exposure in fish, therefore assessing the environmental and commercial impact on fish15.

Governments around the world are beginning to take notice of the microplastic issue. Many have already taken steps to better manage macro-sized plastic waste. From councils implementing separate recycle bins to companies using recycled materials in their products. In 2013, a total of 464,433 tonnes of plastic waste was collected and over the past 20 years nearly 50 billion bottles were saved from the landfill16. It is hard to say how much of this was actually recycled but it is a step in the right direction.

With legislation on the use of microbeads hopefully on its way, the cosmetic industry has sensed the changing winds and have begun removing microplastics from their products. Whether large multinational corporations such as Unilever, Johnson & Johnson, L’Oréal, Procter and Gamble and Asda (who have begun removing them thus far)17 return to a natural, or entirely new, alternative remains to be seen.

What Can Still Be Done?

Microplastics are a global issue, meaning there is not a single solution. It will require everyone: from the individual, to corporations, to governments to make changes in the way we use and dispose of plastics. Pressure from groups like the Plastic Soup Foundation, Fauna & Flora International and the Marine Conservation Society have helped bring the issue of microbeads to the attention of the public and government. It is now likely that microbeads will be removed from cosmetic products and legislation put in place to restrict their use.

There are other things that can be done to help. The first, and most obvious, thing we can all do is to recycle our plastic waste. Clothes that are made from synthetic fibres like polyester produce microfibres in the wash, washing these garments less often will reduce the amount of microfibres they release into the environment18. Until all cosmetic products are free from microplastic, we should try and limit our use of these products. To help with this, the Plastic Soup Foundation & Stichting De Noordzee have produced a free mobile app that allows the user to check whether a particular product contains microbeads. For the app and for more information about microbeads, check out beatthemicrobead.org.

However, there needs to be a greater effort made to improve the ways in which we recycle. This comes down to improving education about the issue at all levels, from citizen to government. At the moment, recycling schemes vary from council to council, as the budgets and resources vary between regions. In an ideal world there would be a standardised recycling scheme. This scheme would reduce confusion about what can and can’t be recycled, as well as allowing industry to better design packaging with this strategy in mind. With the oceans collecting our plastic waste, there needs to be more done to clean up the marine environment. Examples of this could be through volunteering schemes, government initiatives or corporate publicity. Microplastics and the general issue of plastic waste is something we all contribute to. Unless we work together, the problem can, and will, only get worse.

References

- Natalie Wolchover, livescience. Why Doesn’t Plastic Biodegrade? (accessed 25th August 2015)

- Kari O’Connor, postconsumers. How Long Does It Take a Plastic Bottle to Biodegrade? (accessed 25 August 2015)

- Eric T. Schneiderman. Unseen reat: How Microbeads Harm New York Waters, Wildlife, Health And Environment. New York Office of the Attorney General. 2014. (accessed 25 August 2015)

- Ritter L; Solomon KR; Forget J; Stemeroff M; O’Leary C. Persistent organic pollutants. United Nations Environment Programme. 1997. (accessed 17 August 2015)

- Stockholm Convention. The 12 initial POPs under the Stockholm Convention. (accessed 17 August 2015)

- Takada, H., 2006. Call for pellets! International Pellet Watch Global Monitoring of POPs using beached plastic resin pellets. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 52 1547- 1548 (accessed 25 August 2015)

- Akpan, Nsikan, Science News. “Microplastics Lodge in Crab Gills and Guts.” (accessed 25 August 2015)

- Alison Pearce Stevens, Student Society for Science. (accessed 25 August 2015)

- Jean-Pierre W. Desforges, Moira Galbraith and Peter S. Ross. Ingestion of Microplastics by Zooplankton in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2015. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00244-015-0172-5 (accessed 25 August 2015)

- Plastic Soup Foundation. Microplastics: scientific evidence. (18 August 2015)

- European Commission. Plastic Waste: Ecological and Human Health Impacts. 2001. (accessed 26 August 2015)

- Michael Graham Richard, Treehugger. Canada to say ‘no thanks’ to plastic microbeads in personal care products. (accessed 19th August 2015)

- The Hon. Greg Hunt MP, Minister for the Environment. Taking action to tackle harmful marine debris. 2015. (accessed 26 August 2015)

- Ned Stafford, Chemistry World, Europe mulls laws to tackle Microplastic scourge. (accessed 19 August 2015)

- T. Katzenberger and K.Thorpe. Assessing the impact of exposure to microplastics in fish. Environment Agency. Project Number: SC120056, 2015. (accessed 26 August 2015).

- Recoup. Uk Household Plastics Collection Survey 2014. (accessed 26 August 2015)

- Beat the Microbead. Companies that have pledge to stop using microbeads.(accessed 19th August 2015)

- Gregg Treinish, National Geographic. Fleece to Food: Explorer Gregg Treinish on Microplastics. (19 August 2015)