The war against superbugs continues, as antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remains one of the most urgent global health threats according to the WHO. This November, World Antibiotic Awareness Week (WAAW) aims to “increase global awareness of antibiotic resistance and to encourage best practices among the general public, health workers and policymakers to avoid the further emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance”1. I attended a student-run conference on AMR to hear about the latest in the field, and to find out what we can do to conserve antibiotics.

The Silver Bullet

Antibiotics were a brilliant accident that changed the world, revolutionising modern medicine and preventing millions of deaths across the globe. In 1928 Alexander Fleming, a Scottish researcher working with the influenza virus at the time, left his staphylococcus culture plates in the lab while he was on holiday (he was commonly described by his colleagues as careless!). He returned to find his plates had moulded, and that the mould had prevented his bacteria from growing. Fleming had discovered an antibiotic — namely penicillin — a bacteria-killer that was eventually developed into a medicine to treat streptococcal septicaemia in the 1940s, and then went on to become the most widely used antibiotic in the world to date. Antibiotics are now used globally to treat bacterial infections in humans, animals and crops. So what happened to the so-called “magic pill”?

Resistance Strikes

Antimicrobial resistance occurs in bacteria when they are repeatedly exposed to medicines such as antibiotics and subsequently evolve to fight back. This renders the medicine, in effect, useless. We can think of this as an evolutionary arms race: we expose bacteria to antibiotics to kill them, creating what is known as a “selective pressure” on bacterial species to quickly adapt in order to survive. Routine exposure speeds up this race, and eventually, one bacteria will have some adaptation that will render it resistant to an antibiotic’s mechanism of killing. This bacteria will divide, spreading its resistance genes to its colony and beyond by a process called horizontal gene transfer, which is when bacteria pass genetic material to unrelated organisms. This allows bacteria to quickly acquire useful traits from other bacteria nearby, including antibiotic resistance genes. Us humans then need to find a new antibiotic with a new mechanism to fight back. Up until the last decade we did just that, finding variations of new antibiotics at least every year. However, bacteria, as the class of life from which all others originates, have pretty clever and extremely quick ways to adapt, evolve and ultimately beat us by a mile in the arms race. With new antibiotics losing their effectiveness even quicker than the ones before, and the slow-rate at which new medicine can go from conception to human consumption, it has become unsustainable, and unprofitable, for pharmaceutical companies to continue looking for new antibiotics. As such, there has not been a new class of antibiotics discovered since 19622. The number of multi-drug resistant bacteria is, however, multiplying.

An Unlikely Ally

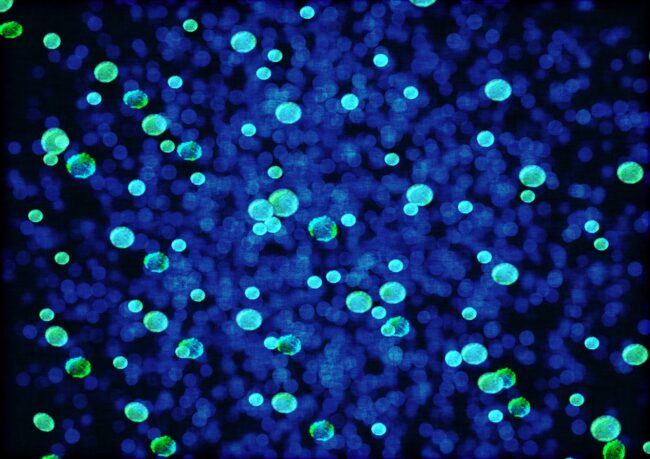

One of the most interesting talks from the AMR conference was given by Professor Liz Sockett of the University of Nottingham, who is searching for innovative solutions to the antibiotic crisis. Liz’s lab studies the bacterium Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, which is predatory to other bacterial species. These friendly bacteria have been found to attach, invade, replicate and then burst open other bacteria, including the antibiotic-resistant pathogens that threaten human health3. Here, we have our unlikely ally in the superbug war — bacteria themselves. Can we use these predatory bacteria serve as an alternative medicine to eliminate pathogenic bacteria infections?

In Professor Sockett’s lab, Bdellovibrio have been injected into living host animal models, and successfully killed Gram-negative pathogens living inside the infected host. They have studied the inflammatory response in the host after Bdellovibrio injection, and found that there is little negative reaction. In fact, Bdellovibrio appears to help the host even more by stimulating the hosts own immune response against the pathogen. Although friendly, Bdellovibrio is still recognised as foreign in the host, and are cleared out by the security guard cells, macrophages, after 48 hours. However, this is still enough time for our friend Bdellovibrio to do its work, and act as an effective treatment against bacterial infections. Professor Sockett and her team are now looking to make the move to humans. So far, there have been positive signs, including successful treatment in zebrafish embryos and human cell cultures, indicating that Bdellovibrio can be used as a dose in future medicine safety trials.

At the end of her talk, Professor Sockett left us with an anecdote about a community that when sick, were told to take water from a so-called “healing spring” known amongst the local people to act as a natural treatment for bacterial infections. The magic healing spring has, you guessed it, Bdellovibrio living in it. In fact, Bdellovibrio are found globally in nature and man-made environments. Although there are many hurdles to overcome before our friendly bacteria allies are used as a medicine, it is both exciting and comforting that new solutions are being sought. In the meantime, what can we do to prevent antibiotic resistance spreading?

Become an Antibiotic Guardian

The future of antibiotics depends on all of us. Common treatments for minor injuries and infections to treatments for cancer and preventing infections from surgery all rely on antibiotics. As such, without working antibiotics, modern medicine is under serious threat. To slow resistance, unnecessary use of antibiotics needs to be cut across all sectors, globally. Students, scientists, health care professionals and all members of the public can choose their pledge and become an antibiotic guardian here4. As an antibiotic guardian, you are committing to take action to help prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. This can be by spreading awareness, educating your peers, only taking antibiotics exactly as prescribed or by participating in collaborative antibiotic resistance research. Let’s take our doctors advice, spread awareness and help keep our antibiotics working.

This article was edited by Kirstin Leslie.