An exciting collaboration between scientists at Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory in New York and the University of Cambridge has revealed that breast cancer cells can mimic blood vessels. This ability allows the cancerous cells to create exit routes from the tumour, allowing it to spread throughout the body. They have pinpointed the molecular signals that allow the cells to create these tubular networks within the tumour, which could be a promising drug target to slow the spread of breast cancer in the future.

We are still discovering how and why different cancers can spread more effectively than others. Brest cancer has a particularly high propensity to spread, making it dangerous if not caught early. The original or ‘primary’ tumour forms within the breast tissue. These tumours are extremely complex, formed not only of cancerous breast tissue cells but many other types of cells. Many aspects of a tumour can contribute to its ability to spread. Often, one tumour cell will mutate, becoming unique to the other tumour cells, which gives it the ability to leave the original tumour and enter the blood or lymphatic system. These transport systems then deposit escapees in other organs, forming metastasis.

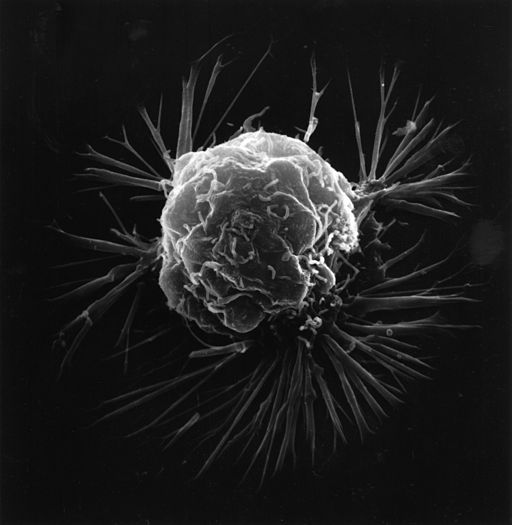

Using a mouse model of breast cancer, the researchers discovered that cancerous cells within the original tumour could transform into tubular networks, similar to blood vessels, allowing blood to flow around the tumour, supporting its growth. These channels also provide an escape route for tumour cells to flow out from the primary tumour, colonising in other parts of the body.

Their mouse model allowed the researchers to track the fate of similar types of tumour cells that have mutated in similar ways. They discovered that the tumour cells that mimicked blood vessels were releasing two unique proteins called Serpine2 and Slpi. These proteins were found to drive the formation of vessels and act as an anticoagulant to thin the blood, allowing it to flow freely. This suggests that these proteins may drive the ability of some tumour cells to spread throughout the body.

Interestingly, when the researchers looked at the role of these proteins in human breast cancer, they discovered them to be at particularly high levels in patients that had lung metastatic relapse. Overall, these discoveries help us understand how individual tumour cells transform to aid their own metastatic spread, and provide a potential therapeutic target to slow the spread of breast cancer in the future.

Edited by Debbie Nicol