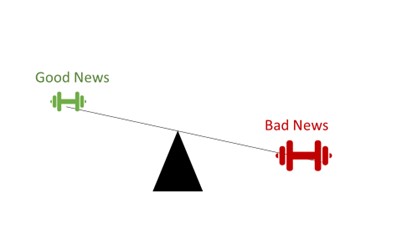

Not all news is created equal. We are wired to react to bad news quicker, stronger, and for longer. We also perceive negative news in more varied ways than we do positive or neutral news. This effect is even more pronounced for personal experiences[1]. Rozin and Rozyman (2001)[2] studied this effect in a variety of fields, in both humans and animals. They also provide several theoretical explanations for this so-called negativity bias[3].

From an evolutionary perspective, it makes sense that we have a negativity bias. Our ancestors likely relied on their ability to respond quickly and effectively to negative situations to survive, in both individual and group contexts. In our hunter-gatherer past, where every day presented potential dangers, success had to be achieved consistently, while failure could occur just once. This asymmetry may be the root of negativity bias, with individuals genetically-predisposed to paying more attention to negative news surviving longer and passing on their genes.

However, instincts that served us well in the hunter-gatherer days might be troublesome in today’s ‘era of the global village’ where news is instant and often unreliable. This problem is further accentuated by social media algorithms designed to maximise engagement. Negative news and emotions tend to generate more engagement than positive or neutral content. As a result, negative news and emotions are disproportionately promoted on social media. This can have negative effects on mental health and wellbeing, as noted by studies such as those by Rosen et al. (2013)[4] and Jha et al. (2016)[5]. Conscious efforts need to be undertaken to minimise these effects through awareness of the negativity bias and by maintaining a healthy dose of positive news in our media consumption.

The Power of Bad[6] by psychologist Roy Baumeister and New York Times journalist John Tierney discusses the implications of negativity bias in our daily lives and ways to counteract it. For example, it notes:

- We don’t reward people adequately for going the extra mile, but tend to be severely critical of those who fall short.

- The ‘sandwich approach’[7], quite widely used in giving feedback, recommends that criticism should be sandwiched between positive comments. However, due to negativity bias the positive comments tend to be forgotten by the recipient. This results in undermining the feedback, and has a deleterious impact on the relationship between the employee and the manager.

Awareness of cognitive biases such as the negativity bias will help us better navigate life by harnessing their power and minimising the potentially damaging consequences.

[1] Vaish A, Grossmann T, Woodward A. Not all emotions are created equal: the negativity bias in social-emotional development. Psychol Bull. 2008 May;134(3):383-403. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.383. PMID: 18444702; PMCID: PMC3652533. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3652533/

[2] Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296-320.

[3] The negativity bias, neuroplasticity and how to rewire the anxious brain #LewisPsychology

[4] L. D. Rosen, K. Whaling, L. M. Carrier, N. A. Cheever, and J. Rokkum. 2013. The Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale: An empirical investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 6 (November, 2013), 2501–2511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.006

[5] Jha, A., Lin, L. & Savoia, E. The Use of Social Media by State Health Departments in the US: Analyzing Health Communication Through Facebook. J Community Health 41, 174–179 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-015-0083-4

[6] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/44902133

[7] https://hbr.org/2013/04/the-sandwich-approach-undermin

Edited by Hazel Imrie

Copy-edited by Rachel Shannon