It is well known that bacterial resistance is growing at a worryingly rapid rate worldwide and, as such, has become a high priority for the World Health Organisation. It has been estimated that approximately 10 million people will die every year due to antibiotic resistance (AMR)1 and it has become increasingly imperative that we find novel interventions to circumvent this. Despite new anti-bacterial compounds regularly entering the market, the rate of AMR remains high and bacteria remain highly resilient in overcoming novel antibiotics. The need for a dynamic, actively evolving therapeutic has never been more necessary.

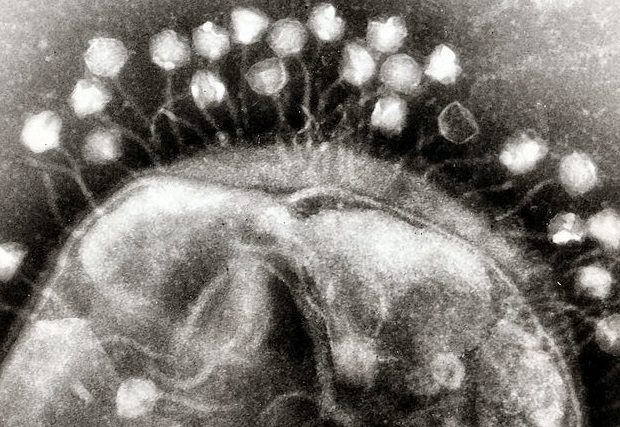

The answer to this could be bacteriophages: viruses that specifically attack bacteria. Each bacteriophage is specific to a particular strain of bacteria – for example, an Escherichia coli (E.coli) bacteriophage will only attack an E.coli bacterium. The name bacteriophage literally means ‘bacteria eater’ and their greatest strength lies in their ability to evolve with their host, therefore circumventing bacterial resistance. These handy viruses have been recognised for their anti-bacterial properties for many years – and the use of them has been termed ‘bacteriophage therapy’. Bacteriophages were first exploited for their therapeutic potential in the early 1900s by George Eliava, a Georgian microbiologist who founded the Eliava Institute in 1923 to push the development of bacteriophage therapy2. Currently, bacteriophages are being used to treat bacterial infections in which conventional therapies have failed, including bacterial Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the common cause of chronic lung infections. These unique treatments have remained isolated in Russia and Georgia but in 2005 were introduced to Poland, the only European country in which bacteriophage therapy is actively used. The advantages of using bacteriophages as an alternative to antibiotics are known widely in the science community: they have low toxicity due to their specificity to bacteria, they have a minimal impact on the normal flora which are important for gut health and which can be harmed by regular antibiotics, and there is a narrow window for bacterial hosts gaining resistance against their specific phage.

On paper, bacteriophage therapy appears to be a highly efficient alternative to current antibiotics. However, there are disadvantages associated with its global implementation. First and foremost, there is a requirement to convince a generally sceptical public, as many are unsure of what viruses are, how they could work as a therapy, and how they differ from bacteria. Bacteriophages also have a low target range, limiting possible alternative treatment options3.

Despite potential challenges, bacteriophage therapy is a compelling alternative to the conventional chemical antibiotics currently on the market. With greater public engagement and education, bacteriophages could be applied soon to tackle AMRs and provide more ammunition in our arms race against dangerous and highly resistant bacterial disease.

Edited by Kirstin Leslie

References

- World Health Organisation statement on bacterial resistance: http://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/en/

- For more information on bacteriophages, please visit: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC90351/

- For more information on the positives and negatives of bacteriophage therapy, please visit: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3278648/