What springs to mind when you think about memory? Whether it’s a string of dates from World War II, a fond recollection of a beloved family pet, or even a vague thought of what you ate for breakfast this morning, our memories are the basis of everything we know and everyone we care about.

We tend to regard our memories as film-like reproductions of past events which are filed dutifully away, ready to be replayed on demand. It is therefore rather frightening to consider that the foundations of who we are instead rely on delicate and intricate patterns of neural connectivity, which can easily be thrown off balance. Additional information and beliefs can invade memories and perhaps even permanently alter them. In fact, when given additional suggestive information we believe to be true, the brain fills in any gaps with things that match this belief.

For example, in one study 1 by the notable memory researcher Elizabeth Loftus and colleagues, participants were given an advert for Disneyland in which Bugs Bunny was featured. Subsequently, they were asked if they had met Bugs Bunny and shaken his hand on their trip to Disneyland. Despite the fact that Bugs Bunny is a Warner Brothers character, and therefore would not be found at Disneyland, a significant proportion of participants reported having met the character.

The misleading poster had been enough to trick the memory of some participants in the study. Psychic mediums, psychotherapists and law enforcement authorities have all been accused of employing similar techniques of introducing false or additional information, either inadvertently or deliberately, leading to false memories of events 2.

How can you protect your memories from invasion and why might they be so easy to infiltrate? It helps to know that memories are most fragile upon first forming. Brain cells, known as neurons, first form connections with one another to create a memory trace. A memory may constitute many different kinds of perceptual information such as sights, sounds, and smells, which depend on the activation of neurons from different brain areas. This information is thought to be stored in a brain area known as the medial temporal lobe (MTL). Here, memories undergo a process of consolidation, in which these connections are strengthened and become more stable. In this view, memory is akin to drawing an arrangement of lines on a piece of paper and continuously sketching over them with a pencil until they are permanently ingrained into the paper. While the traces of memory seem to be initially embedded in the MTL, this theory suggests that long term memory storage depends on the anatomical relocation of memory patterns to the outer cortex where they remain, perhaps for many decades.

However, a more recent theory known as ‘Multiple Trace Theory’ 3 suggests that when we recall a memory, the long term trace in the cortex and the MTL both become active for a short period of time. As the MTL is the site of consolidation, renewed activation (reconsolidation) may underlie the susceptibility of memory to alteration. To return to the same analogy, just as your pencil could veer off track and leave a mark outside the defined lines on every repeat drawing, our memories are vulnerable to losing a few details or adopting a couple of stray connections during these short windows of reactivation.

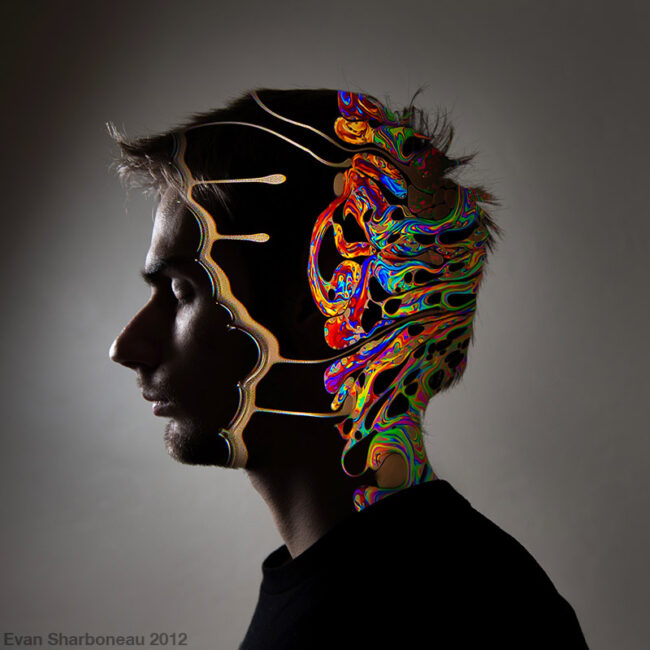

The beautiful complexity of our inner network

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nyphysicaltherapy/25814246922

What can possibly be good about the discovery that our brains are so prone to forming false memories? Some researchers believe that our malleable memories are adaptive and essential for the updating of information in our environment. Happy memories with a person you may now thoroughly dislike may not be recalled intact; instead, they may be clouded by the disdain you now hold for that individual as you remember them in a more negative light. In short, memory is reconstructive, not reproductive, but this may help us make sense of our ever-changing environments 4.

This flexible approach to memory also happens to be the foundation of a ground-breaking new approach to the treatment of mental illness, which you’d be forgiven for thinking was straight out of a questionable science fiction film. The removal of specific memories has been experimentally induced in rodents by activating the memory trace and utilising pharmacological interventions to prevent reconsolidation. In a now classic study 5, mice were conditioned to fear two distinct tones which were consistently followed with an electric shock. However, if mice were induced into a state of amnesia with a new experimental drug, and the tone was played, the fear memory was no longer reactivated.The following day, mice treated with the drug failed to respond to this sound but continued to show fear behaviours upon hearing the other tone, indicating that the memory appeared to have been selectively altered. You may be thinking that we are still very far from an “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” situation in which scientists can alter painful human memories. In the opinion of some scientists, you should think again.

In the realm of brain disorders, Alzheimer’s is perhaps the first which comes to mind when thinking about memory. However, many psychological disorders may be heavily based on positive or negative memory associations. Recently, scientists were able to use this technique to treat cocaine-addicted mice by interfering with positive memories of cocaine use 6. In the world of brain sciences, altering rodent memories has actually been demonstrated in a great number of studies stretching over the past decade 7. However, a new surge of research illustrating similar effects in human subjects has brought with it the possibility that such procedures could aid the treatment of psychological disorders. Can phobias be reduced through altering the fear associations which create them? Can Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) be attenuated by removing painful memories of the past? Can addictions be unlearned through removing the positive associations addicts form with drugs of abuse 8?

In humans, this unusual form of therapy has already been shown to be a useful tool in reducing phobias, and many studies are underway to test the efficacy of altering memory reconsolidation in other conditions. Memory extinction therapies may one day be available, paired with drugs designed to block the neural connections and chemicals required for memory formation, both of which may be prove to be effective new weapons against psychological illness.

Altering our memories is without doubt a daunting thought. Alongside it are some serious ethical and moral considerations which the scientific community and the general public will need to consider. Furthermore, some critics argue that such findings should be taken with a large pinch of salt. The techniques with the potential to alter memories in mice may not always work when faced with the complexities of the human brain. However, though we view our memories as precious things, it seems that they may be created to be updated. In a world in need of new approaches to mental illness, it may be a thought worth exploring.

This article was specialist edited by Gabriela de Sousa and copy edited by Manda Rasa Tamošauskaitė

References

- This study and others are featured in this review of Loftus’s memory research http://faculty.washington.edu/eloftus/2003Nature.pdf

- An insightful TED talk from Elizabeth Loftus herself on false memories: https://www.ted.com/talks/elizabeth_loftus_the_fiction_of_memory?nolanguage=en

- Both theories are discussed here http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11559-007-9003-9

- An easy to read overview of memory reconsolidation theories – http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982213007719

- http://www.nature.com/news/2007/070305/full/news070305-17.html

- Read all about it — http://gizmodo.com/scientists-use-light-to-alter-memories-of-cokehead-mice-1760548705

- A good summary of past, current, and future research in this area http://www.apa.org/monitor/2015/02/bad-memories.aspx

- An interesting video from Nature which describes how memory interventions may be useful in the treatment of alcohol dependence: http://www.nature.com/nature/videoarchive/addiction/index.html