I first began to understand Parkinson’s disease nearly a decade ago, when I was a still in school. My grandfather, an extremely kind and generous man who was accustomed to his active lifestyle as a farmer in rural Ireland, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in his seventies.

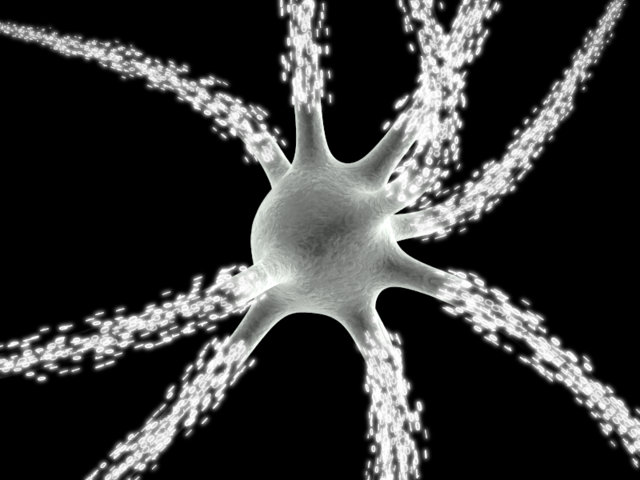

Parkinson’s is a progressive neurological condition caused by a lack of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain. This dopamine deficiency arises from the death of neurons, the cells responsible for the production of this chemical. As a result, communication between the brain and the body is less effective, leaving the patient with motor symptoms such as a tremor, rigidity and slowness of movement. Nearly 200 years after the discovery of this disease, we have no real understanding of why Parkinson’s disease develops. However, we do know it can be attributed to combination of genetic and environmental factors unique to each patient.

Now ten years on, my grandad manages his condition with a bewildering array of drugs, to be taken at varying times during the day and night, aided at all times by my grandmother. As a research scientist, I wonder what do we actually understand about this disease, and how can we advance its treatment?

A large group of collaborating scientists, lead from Harvard Medical School in Boston, have advanced the possibility of tailoring treatments to each patient’s form of Parkinson’s1O. Coleman and H. Seo et al, Science Translational Medicine, 2012, Vol. 4, Issue 141, DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003985.2. The scientists were able to remove skin cells from those affected and unaffected by Parkinson’s and program these cells to transform into basic cells called stem cells. As of yet these cells have no specific function, like those found in the developing embryo. The undifferentiated cells were then induced to become neuronal cells like those found in the brain. The group then studied these patient-derived neurons to understand how they function differently to those produced from those unaffected by Parkinson’s disease, and how well they respond to different treatments. They discovered that neurons from patients suffering from Parkinson’s were more likely to die after exposure to toxins that destroy the cells’ energy-producing components, suggesting these structures are weakened during the progress of this disease.

These cells could be a valuable tool to help deepen our understanding of why neurons begin to die in patients with Parkinson’s, and develop ways of keeping them alive for longer to delay onset of this disease. They could also be used to test which treatments are most effective for each patient, which would help determine sub-groups of patients of clinical trials of new drugs. Advances like these are crucial to help improve the lives of those suffering with and caring for those with Parkinson’s, like my grandparents. Hopefully they will pave the way to more effective treatments, leading to fewer drugs with longer-term effects allowing people like my granddad to do more of the things they enjoy.

Edited by Debbie Nicol