Scientists from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York have revealed that cancer cells are able to colonise the brain by grabbing on to blood vessels and ignoring death signals emitted by other brain cells 1.

This important finding, published in the prestigious journal Cell, is a step forward in our understanding of how cancer cells spread from the original tumour to other organs in the body. Cancer spread, or metastasis, is the main reason people die from their cancer. For this reason, we need to understand how cancer cells do this in order to stop them.

To spread, cancer cells invade the surrounding tissue and when they reach the blood vessels, they use them and the lymphatic system as a highway. They can ‘hop off’ at organs along the way where they make additional colonies. Very few cells are able to colonise the brain as they must cross the blood brain barrier, a highly selective barrier that protects the brain. But what allows these few cells to do this?

Using models of lung and breast cancer, Dr. Massagué and his team have discovered that some cancer cells use stealth tactics to grow in the brain unnoticed. Normally the most common cells in the brain, called astrocytes, release a chemical death signal that forces the cancer cells to self-destruct. By focusing on a group of genes previously linked to metastasis, they discovered that the special cancer cells that escape destruction do so by secreting a protein called Serpin. This combats the death signal, allowing these cells to survive and colonise the brain.

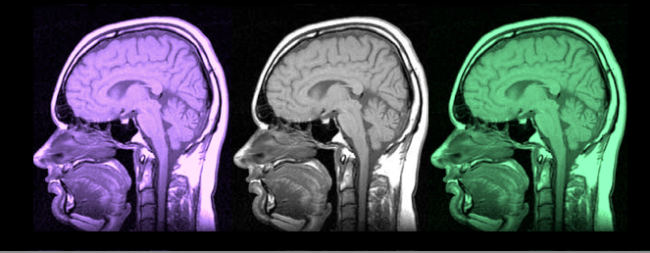

By imaging brain tissue, the group could see the cancer cells that were able to grow in the brain. Amazingly, these successful cells were able to cling onto blood vessels in the brain and grow around them, gaining nutrients and protection, eventually forming a tumour. If the cells can’t cling in this way, they fall off and are destroyed by astrocytes.

Since the ways in which these few cancer cells take hold in the brain are the same in both lung and breast cancer, it may suggest a common factor important for metastasis to the brain. These findings change the way we look at metastasis formation, and provide new avenues for therapeutic intervention, either by boosting the bodies natural defences or by preventing tumour evasion of death signals.

Edited by Debbie Nicol