theGIST Reports: Travels in Lands that Don’t Exist, a Presentation by Professor Iain Stewart

Image Credit: Rock365 via Flickr ( License )

The cliché response to any mention of geology in everyday conversation is, “Rocks and stuff right? Boring!” Unfortunately and unjustly, this is the prejudice and barrier that Professor Iain Stewart must combat constantly as a presenter and academic of geology. Everyone including academics will recognize Prof. Stewart as “that telly presenter,” which even he, himself, will admit. He has popularized geology through various television programmes, such as the BBC’s Earth: The Power of the Planet (BAFTA nominated), The Climate Wars, and most recently Rise of the Continents, which comprised the main material for his current series of presentations 1 2 3. However, Prof. Stewart is also an active geologist, currently holding the title of Professor of Geoscience Communication at Plymouth University 4, and is an alumnus of the University of Strathclyde with a BSc in Geography and Geology, a degree that is no longer offered at this institution. He was back visiting his alma mater on 1 May 2014 to give a presentation as part of the Engage with Strathclyde week 5.

Prof. Stewart began his presentation by addressing the issue raised above: why is it so difficult to convey the interesting features of geology? In fact, this is not a problem unique to geology but all sciences. As humans, we are unavoidably hindered in our perception by the time and length scales in which we exist. Communicating the details and evidence of physical entities that are too small to observe with our own eyes, distances on our own planet too large to comprehend, and timescales a near infinity longer than our own lifetimes is the formidable task posed to geologists specifically. Prof. Stewart’s proposed strategy for solving this problem is quite simple in principle: present geology to people through media to which they can directly and immediately relate.

As an example, Prof. Stewart sought to express how the geological theories of Pangaea and plate tectonics have influenced the New York City skyline: it sounds like a loose connection, but this is what makes it all the more interesting. If you are unfamiliar with the terms, plate tectonics is the theory that the Earth’s lithosphere—its cool outer crust—is composed of enormous plates that are constantly moving, albeit quite slowly, and this movement has facilitated different arrangements of the Earth’s continents. The most famous is the supercontinent, Pangaea, which occurred about 300 million years ago 6, 7. These theories pervade and underpin all of modern geology, but with speeds of mere centimetres per year for moving plates leading to timescales of millenia for any noticeable change, one quickly understands the difficulties of explaining these theories: over many generations of human lifetimes, the lithosphere appears static and unchanging, despite being, in reality, constantly dynamic.

Figure 1: An aerial view of Manhattan including Midtown (lower left) and Downtown (upper right).Image Credit: Global Jet via Flickr ( License )

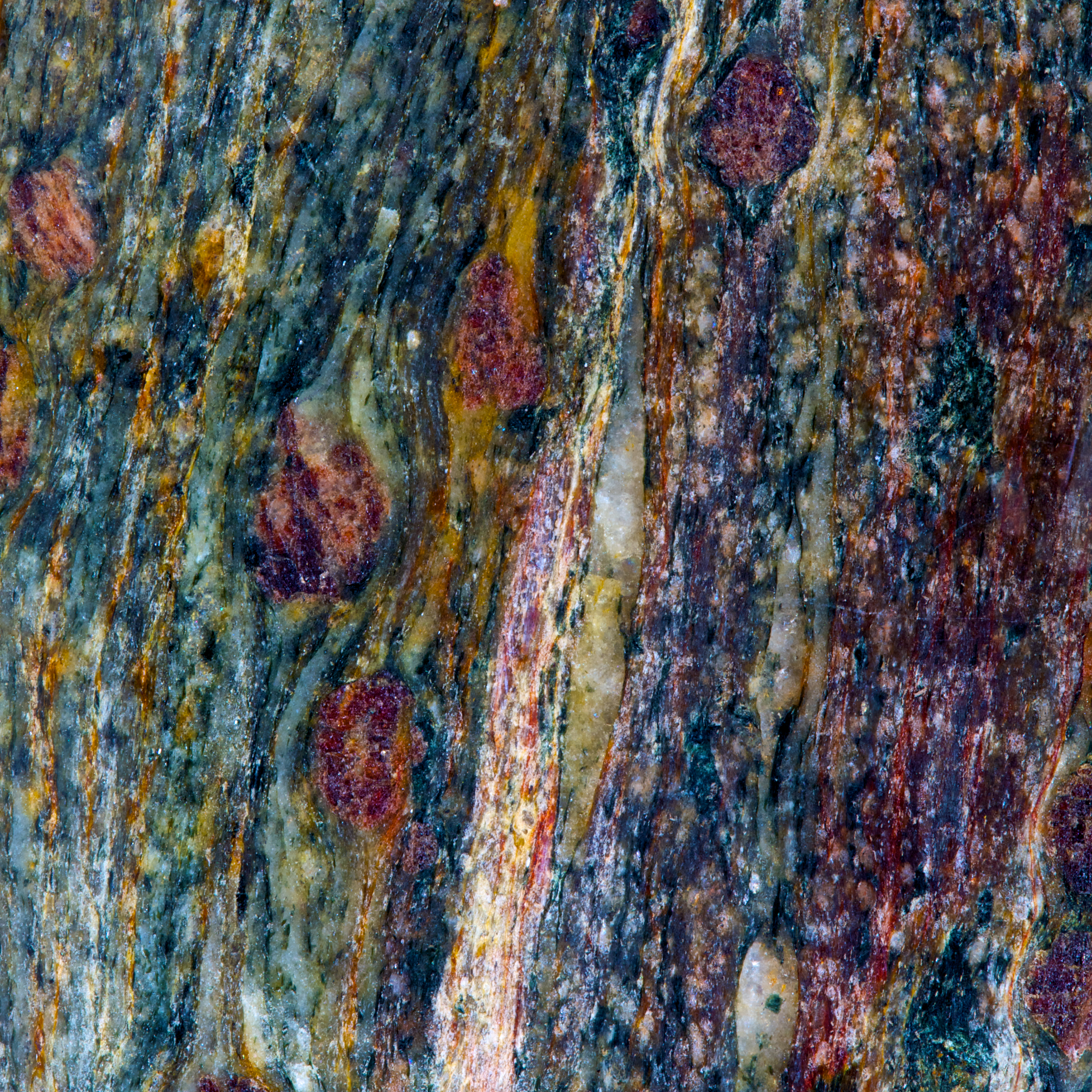

The image of Manhattan Island is familiar to most with its towering skyscrapers, but there is one peculiar feature of this scene that you may not have noted before. All of the skyscrapers are concentrated in two distinct areas: the tip of the island—downtown—and a small separated spot near the middle—midtown (see Figure 1). In order to determine the cause of this, Prof. Stewart aptly pointed out that one must ask a question that few people ask: what is underneath New York City? Geologists have discovered two materials of interest; the most important is Manhattan schist, a metamorphic rock with sheet-like grains in a preferred orientation, as in Figure 2, formed because of high pressure and temperature. The other is glacial till, a soft muddy soil formed by the dragging forces of the receding glaciers. Skyscrapers require a sturdy, non-compressible base to build upon, and this can be provided by the schist while it is not possible for the soft till. Therefore, wherever one sees skyscrapers in Manhattan, one also knows that schist is underneath.

Figure 2: A garnet mica schist (Glen Sluan Schist) from near Clachan, at the northeast end of Loch Fyne, Argyll and Bute, Scotland. Keele Collection. Manhattan schist is not colourful like this, but the colours help observe the grain structure of schist more easily.Image Credit: Rock365 via Flickr ( License )

This is a pleasant narrative, but Prof. Stewart still needed to connect it to the ideas of plate tectonics and Pangaea. As mentioned above, schist requires specific conditions to form, and in this case it was determined that the schist underneath Manhattan must have been formed in the root of a gigantic mountain range, larger than the Himalayas. In other words, this type of schist is conclusive evidence that a huge mountain range once ran through New York when all of the continents were ‘squished’ together in Pangaea. The separation of Pangaea and the retreat of the glaciers eroded this mountain where New York City presently lies, but the Appalachian Mountains are remnants of what is left. Now, when you see or think of Manhattan Island, you will be reminded of how plate tectonics and Pangaea shaped its appearance and hopefully realize how influential these theories are, exactly as Prof. Stewart set out to achieve.

However, it was not just relatable narratives like these that made Prof. Stewart’s presentation interesting and effective at communicating geology. His humour and polished persona contributed to its efficacy in ways far above the average academic, evidently due to his experience on television. He showed clips of the continuously erupting Stromboli, the Mediterranean’s most active volcano, and described it as “volcano porn” for geologists, inciting many snickers from the audience. This was expertly woven into his narrative of how the Mediterranean is gradually shrinking due to the movement of the Eurasian and African plates, causing a subduction zone and volcanic activity. Clips of Prof. Stewart pinning down a live alligator also caused looks of apprehension in the audience and a few laughs. One might question how alligators have anything to do with geology, but Prof. Stewart was self-aware of this observation and provided a convincing argument.

Alligators are the closest relatives to the animals that would have dominated the planet for some of the geological eras relevant to Prof. Stewart’s presentation. So, not only does having a geologist wrangle an alligator provide an intimate picture of these animals that viewers can relate to—much easier than inanimate rocks—but it also provides an essential piece of entertainment. Prof. Stewart acknowledged that regardless of how interesting the science might be, a constant barrage of scientific facts and methods will tire even the most devote science geek. These entertainment bits may seem like they cheapen the science, but they relax and draw in viewers and allow these audiences to form a relationship with the presenter by seeing his or her different facets. Inevitably, this will boost viewership of what is primarily an educational program, so the benefits are undeniable. Furthermore, realizing the importance of mixing entertainment with scientific information is a valuable fact for any science communicator to appreciate.

In the end, Prof. Stewart’s presentation succeeded in being both informative and entertaining, proving for this correspondent that geology is not just about boring rocks but a dynamic planet in constant change when viewed with the correct time resolution. It was also a prime example of how effective T.V. presenters who popularize science can be, and such a position that mixes academia and entertainment should not be frowned upon by either establishment.

References

- BBC. Earth: The Power of the Planet.

- BBC. In the current climate: The Climate Wars

- BBC. Rise of the Continents

- Plymouth University. Iain Stewart.

- University of Strathclyde. Engage with Strathclyde

- Wikipedia contributors. Pangaea

- Wikipedia contributors. Plate tectonics

I am not rattling great with English but I line up this real leisurely

to interpret.